Home > Health insurance Marketplace > Maryland

Maryland Marketplace health insurance in 2025

Compare ACA plans and check subsidy savings from a third-party insurance agency.

Maryland health insurance Marketplace guide

This guide, including the FAQs below, is designed to help you understand the health coverage options and possible financial assistance available to you and your family in Maryland. For many, an Affordable Care Act (ACA) Marketplace (exchange) plan, also known as Obamacare, may be an affordable option.

In addition to federal subsidies, Maryland also offers state-funded subsidies for young adults ages 18-37, helping to make coverage even more affordable for this population (this program was previously available to adults up to age 34, but has been extended to age 37).3 This program had been scheduled to sunset at the end of 2025, but Maryland enacted legislation in 2025 to make it permanent and extend the upper age limit to 40. But the legislation also makes the program discretionary for the exchange, rather than mandatory, giving Maryland’s exchange the option to continue to offer the program or not.4

Maryland also enacted legislation in 2025 that calls for the state to provide supplemental premium subsidies to partially mitigate the impacts of the expected termination of the federal premium subsidy enhancements.5 Assuming Congress doesn’t extend the federal subsidy enhancements, Maryland’s new subsidy program would use the same funding source that the young adult subsidy program has been using. So the young adult subsidy program would be “discontinued or subsumed into” the new, broader state-funded subsidy program.6

Individual and family plans on the ACA Marketplace are available for:

- Self-employed people

- Early retirees needing coverage until Medicare

- Workers at small businesses that don’t offer health benefits

Maryland operates its own state-based exchange called Maryland Health Connection. The Maryland exchange follows an active purchaser model. This means the state negotiates with insurance companies to decide which plans will be available for people to buy.

Aetna Health joined Maryland’s individual market for 2024, and Wellpoint Maryland joined for 2025, increasing the number of options available to Maryland enrollees.7 But Aetna is leaving the Marketplace at the end of 2025 (in every state where they currently offer plans), so Maryland Health Connection will once again have five participating insurers in 2026.8

Maryland established a reinsurance program in 2019, which has kept full-price (unsubsidized) premiums lower than they would otherwise have been.9 Maryland also offers an easy enrollment program, which allows residents to connect with health coverage via their state tax return.

Frequently asked questions about health insurance in Maryland

Who can buy Marketplace health insurance?

To qualify for Marketplace coverage in Maryland, you must:10

- Live in Maryland

- Be a U.S. citizen, national, or lawfully present in the U.S. (see note below)

- Not be incarcerated

- Not be enrolled in Medicare

Starting in 2026, Maryland plans to allow undocumented immigrants to enroll via Maryland Health Connection and possibly obtain state-funded subsidies.11 Maryland obtained federal permission for this in early 2025.12 But the legislation that began this process clarified that state-funded subsidies would only be available if allocated by the legislature.13 That had not happened as of June 2025, so the coverage available to undocumented immigrants in the fall of 2025 might only be full-price plans.

(Washington was the first state to obtain federal permission to allow undocumented immigrants to use the exchange; Colorado operates a separate enrollment platform that undocumented immigrants can use. Both states provide state-funded subsidies for these enrollees.)

Whether or not you qualify for financial assistance with your premium, deductible, or out-of-pocket costs depends on your income and how it compares with the cost of the second-lowest-cost Silver plan in your zip code.

Additionally, to qualify for subsidies, you must:

- Not have access to affordable health coverage through an employer. If you think your employer-sponsored health plan is too expensive, use our Employer Health Plan Affordability Calculator to check if you might qualify for premium subsidies in the Marketplace.

- Not be eligible for Medicaid or CHIP.

- Not be eligible for premium-free Medicare Part A.[efn_note]Medicare and the Marketplace, Master FAQ. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Accessed November 2023.[/efn_note]

- File a tax return (including Form 8962) and if married, you must file a joint tax return14 (with very limited exceptions)15

- Not be able to be claimed by someone else as a tax dependent.16

When can I enroll in an ACA-compliant plan in Maryland?

The Trump administration has proposed a rule change that would set a nationwide schedule for open enrollment, running from Nov. 1 to Dec. 15. If finalized, this schedule will take effect in the fall of 2025. (This provision is also part of the budget reconciliation bill that passed the House in May 2025 and was sent to the Senate for consideration.)17

But for the time being, Maryland’s open enrollment period for individual and family health plans runs from November 1 to January 15.18

- Enroll by December 31 for coverage to start January 1.

- Enroll between January 1 and January 15 for coverage to begin February 1.

Note that the deadline to get a January 1 effective date in Maryland is December 31. This differs from most other states, where the deadline is typically December 15.19 (Again, this could change for 2026 coverage, depending on federal rule changes or legislation.)

Outside of open enrollment, you generally need a qualifying life event, such as losing coverage, getting married, or permanently moving, to enroll or make changes. The qualifying life event will trigger a special enrollment period (SEP).

Note that Maryland is one of several states where pregnancy is considered a qualifying life event, giving a person 90 days from the date of the pregnancy confirmation to enroll in a health plan.20

Some people can enroll outside of open enrollment without a specific qualifying life event. For example:

- Native Americans can enroll year-round.

- People who utilize Maryland’s easy enrollment period can begin the process of obtaining health insurance by checking a box on their tax return.21

People who qualify for Medicaid, the Maryland Children’s Health Program (MCHP), or MCHP Premium can enroll anytime.18

How do I enroll in a Marketplace plan in Maryland?

There are several ways to enroll in an ACA Marketplace plan in Maryland:18

- Online: Go to MarylandHealthConnection.gov to create an account and apply.

- Phone: Contact the Call Center at 855-645-8572. Those who are deaf and hard of hearing use the Relay service. Help is available in over 200 languages.

- Talk to a broker: Get help from an authorized insurance broker through Broker Connect.22

- Talk to a navigator: Get help from one of the local navigator organizations in Maryland.

- Mobile app: Apply from your phone by downloading the mobile app, Enroll MHC.

How can I find affordable health insurance in Maryland?

You can find affordable individual and family health plans in Maryland through MarylandHealthConnection.gov, the state’s ACA exchange.

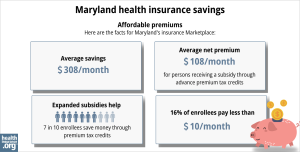

About 76% of Maryland’s exchange enrollees received premium subsidies in 2025, saving about $404 per month on their premiums. These subsidies are called Advance Premium Tax Credits (APTC). With subsidies, Maryland residents pay about $184 monthly on average in premiums (average includes those who pay full price).23

If your income is no more than 250% of the federal poverty level, you may also qualify for cost-sharing reductions (CSR) to lower your deductibles and out-of-pocket costs.24

Thanks to a state-funded subsidy program, young adults aged 18 to 37 may qualify for additional help paying their monthly premiums. This assistance is in addition to the federal APTC.25 Almost 65,000 young adults in Maryland qualified for these additional subsidies during the open enrollment period for 2025 coverage.26

The young adult subsidy program was initially slated to be available in 2022 and 2023, but legislation (HB814 and SB601) enacted in 2023 extended it through 2025. And although it initially only applied to adults up to age 34, the state has extended the eligible age range up to 37.3

Maryland enacted legislation in 2025 to make the young adult subsidy program permanent and extend the upper age limit to 40.4 But additional legislation enacted in Maryland in 2025 directs the state to use the same funding source to provide broader premium subsidies (not just to young people) to partially mitigate the effect of the expected sunset of federal premium subsidy enhancements at the end of 2025.5 So if Congress doesn’t extend the federal subsidy enhancements, Maryland’s young adult subsidy program will be replaced with a broader subsidy program designed to offset some of the higher premiums that people will have to pay when the federal subsidy enhancements expire.6

Source: CMS.gov27

Although Maryland does not have plan standardization, the exchange does offer “Value Plans,” which have lower out-of-pocket costs for certain frequently-used services.28 And for 2024, changes were made to the Value Plans “to make the costs for common health care services clearer and more consistent across insurance companies.”29

For Maryland residents who aren’t eligible for premium subsidies or Medicaid, short-term health insurance can be a lower-cost coverage option, although Maryland limits short-term health plans to three-month durations and it’s important to understand that these plans are not ACA-compliant. For example, they don’t have to cover pre-existing conditions or essential health benefits.

How many insurers offer Marketplace coverage in Maryland?

Six insurers (including two CareFirst entities) offer coverage through Maryland Health Connection in 2025, including one new insurer, Wellpoint Maryland.7

But that will drop to five insurers in 2026,8 as Aetna is exiting the health insurance Marketplaces in all states where they currently offer coverage.

Aetna was new to Maryland’s Marketplace in 2024,30 and their plans were available for 2024 and 2025. But Aetna enrollees will need to select replacement coverage for 2026, during the open enrollment period that begins November 1, 2025. According to the Maryland Insurance Administration, almost 5,000 enrollees have Aetna coverage in 2025 and will need to pick a new plan for 2026.8

Are Marketplace health insurance premiums increasing in Maryland?

For 2026, the insurers that offer individual/family coverage through Maryland Health Connection have proposed the following average rate changes, amounting to an overall average increase of 17.1%. The proposed rate increase would only be 7.9%, however, if Congress were to extend the federal premium subsidy enhancements that are slated to expire at the end of 2025.8

Maryland’s ACA Marketplace Plan 2026 PROPOSED Rate Increases by Insurance Company |

|

|---|---|

| Issuer | Percent Change |

| Aetna Health, Inc. | Exiting the market |

| CareFirst BlueChoice, Inc. | 18.7% |

| CareFirst GHMSI/CFMI | 14.2% |

| Kaiser | 12% |

| Optimum Choice, Inc. | 18.6% |

| Wellpoint Maryland | 8.1% |

Source: Maryland Insurance Administration8

Note that the average rate changes affect full-price premiums, and most enrollees are eligible for premium subsidies and thus don’t pay the full amount. These subsidy amounts are adjusted annually to match the cost of the second-lowest-cost Silver plan.

Maryland established a reinsurance program in 2019, and federal approval was granted in 2023 to extend this program for another five years. The reinsurance program has kept Maryland’s individual market premiums much lower than they would otherwise have been.7 The state is considering various changed to the reinsurance program parameters in 2025, in order to fund the additional subsidies that the state plans to provide if the federal subsidy enhancements expire at the end of 2025.6

If your premiums are increasing from one year to the next, you might want to consider other Maryland Health Connection plans that better fit your budget and offer the benefits you need.

Here’s a look at how overall average premiums have changed each year in Maryland:

- 2015: 1% increase31

- 2016: 20% increase32

- 2017: 25.2% increase33

- 2018: 43.8% increase34 (after accounting for loss of federal CSR funding)

- 2019: 13% decrease35 (reinsurance took effect)

- 2020: 10.3% decrease36

- 2021: 11.9% decrease37

- 2022: 2.1% increase38

- 2023: 6.6% increase39

- 2024: 4.7% increase40

- 2025: 6.2% increase7

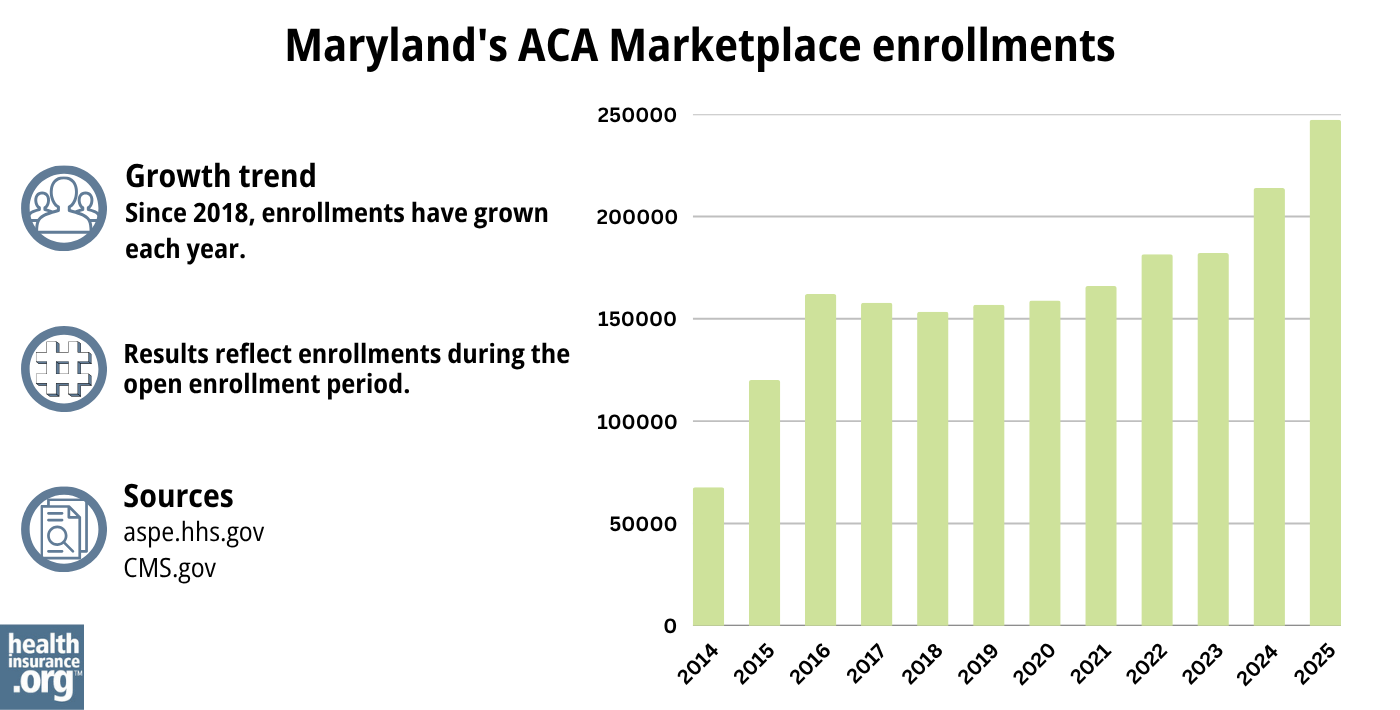

How many people are insured through Maryland’s Marketplace?

247,243 people enrolled in private plans through Maryland Health Connection during the open enrollment period for 2025 coverage.26 This was a significant record high (see below for a chart of prior year enrollment totals).

This surge in enrollment in recent years was due largely to the American Rescue Plan, which improved affordability starting in 2021. The Inflation Reduction Act extended these improvements until 2025, ensuring coverage remains more affordable than it was before the ARP became law.

As noted above, these subsidy enhancements are scheduled to expire at the end of 2025, which will drive full price premiums higher than they would otherwise have been.8

Maryland Health Connection has noted that 70,000 fewer people are expected to enroll in Marketplace coverage in 2026 if the “Big Beautiful” federal budget reconciliation bill is enacted.41

Source: 2014,42 2015,43 2016,44 2017,45 2018,46 2019,47 2020,48 2021,49 2022,50 2023,51 2024,52 202553

Another factor in the enrollment growth in 2024 and 2025 was the end of the pandemic-era Medicaid continuous coverage rule. Medicaid disenrollments resumed in 2023, after being paused for three years. By September 2024, more than 52,000 Maryland residents had transitioned from Medicaid to a private plan obtained via Maryland Health Connection, including more than 28,000 who were automatically enrolled54 (most states did not have an automatic enrollment process for people transitioning away from Medicaid, but Maryland implemented this to mitigate loss of coverage post-pandemic).

Maryland Health Connection reported that more than 14,000 of the people who enrolled during the open enrollment period for 2024 coverage had transitioned away from Medicaid,55 but the disenrollments and coverage transitions had begun in mid-2023, well before the start of open enrollment.

What health insurance resources are available to Maryland residents?

Maryland Health Connection

This is the state’s official health insurance Marketplace, where residents can shop for and enroll in health coverage plans.

Maryland Department of Health

This department oversees various health-related programs in the state, including providing information and managing enrollment for Medicaid.

Maryland Health Education and Advocacy Unit

This unit offers education and support to help individuals understand and navigate their health insurance options, making informed decisions about their coverage.

Health Care Access Maryland

This organization ensures that Maryland residents can access quality healthcare services, assisting with enrollment, navigation, and resources.

Maryland Senior Health Insurance Program

Designed for older adults, this program offers valuable information and assistance related to Medicare.

Louise Norris is an individual health insurance broker who has been writing about health insurance and health reform since 2006. She has written dozens of opinions and educational pieces about the Affordable Care Act for healthinsurance.org.

Looking for more information about other options in your state?

Need help navigating health insurance options in Maryland?

Explore more resources for options in Maryland including short-term health insurance, dental insurance, Medicaid and Medicare.

Speak to a sales agent at a licensed insurance agency.

Footnotes

- ”2025 OEP State-Level Public Use File (ZIP)” Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Accessed May 13, 2025 ⤶ ⤶

- ”Maryland Insurance Administration Approves 2025 Affordable Care Act Premium Rates” Maryland Insurance Administration. Sep. 5, 2024 ⤶

- Young Adult Subsidy Program Expands Age Range. Maryland Health Connection. Accessed November 2023. ⤶ ⤶

- ”Maryland HB297” BillTrack50. Passed Apr. 2, 2025 ⤶ ⤶

- ”Maryland HB1082” BillTrack50. Enacted May 13, 2025 ⤶ ⤶

- ”2026 State-Based Subsidy: Program Parameters Discussion and Proposed and Emergency Regulations” Maryland Health Benefit Exchange, May 19, 2025 ⤶ ⤶ ⤶

- ”Maryland Insurance Administration Approves 2025 Affordable Care Act Premium Rates” Maryland Insurance Administration. Sep. 5, 2024 ⤶ ⤶ ⤶ ⤶

- ”Health Carriers Propose Affordable Care Act Premium Rates for 2026” Maryland Insurance Administration. June 3, 2025 ⤶ ⤶ ⤶ ⤶ ⤶ ⤶

- Reinsurance Program. Maryland Health Benefit Exchange. Accessed December 2023. ⤶

- “Are you eligible to use the Marketplace?” HealthCare.gov, 2023 ⤶

- ”Expanding Health Coverage for Immigrants in 2024: Maryland Health Connection’s Commitment” Maryland Health Connection. Accessed June 20, 2024 ⤶

- ”Letter from CMS to Maryland” Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Jan. 15, 2025 ⤶

- “Maryland HB728” and “Maryland SB705” BillTrack50. Accessed Feb. 16, 2024. ⤶

- Premium Tax Credit — The Basics. Internal Revenue Service. Accessed MONTH. ⤶

- Updates to frequently asked questions about the Premium Tax Credit. Internal Revenue Service. February 2024. ⤶

- Premium Tax Credit — The Basics. Internal Revenue Service. Accessed January 23, 2024. ⤶

- ”How Trump’s ‘Big Beautiful Bill’ threatens access to Obamacare” NPR. June 11, 2025 ⤶

- “Maryland Health Connection Frequently Asked Questions” Marylandhealthconnection.gov, Accessed September 18, 2023 ⤶ ⤶ ⤶

- “Maryland Health Connection Frequently Asked Questions” Marylandhealthconnection.gov, Accessed September 2023 ⤶

- ”Special Enrollment” Marylandhealthconnection.gov, Accessed September 18, 2023 ⤶

- ”Easy Enrollment Program” Marylandhealthconnection.gov, Accessed September 2023 ⤶

- “Maryland Health Connection Find Help” Marylandhealthconnection.gov, Accessed September 2023 ⤶

- ”2025 Marketplace Open Enrollment Period Public Use Files” CMS.gov, Accessed June 11, 2025 ⤶

- “Federal Poverty Level (FPL)” HealthCare.gov, 2023 ⤶

- “Young Adult Premium Assistance” Maryland Health Connection, Marylandhealthconnection.gov, Accessed November 2023 ⤶

- ”Nearly 250,000 Enroll for 2025 Plans Through Maryland Health Connection” Maryland Health Connection. January 17, 2025 ⤶ ⤶

- “2025 Marketplace Open Enrollment Period Public Use Files” CMS.gov, May 2025 ⤶

- ”All About Value Plans” Maryland Health Connection. ⤶

- Maryland Health Connection’s Open Enrollment For 2024 Health Plans Starts Today, November 1. Maryland Health Connection. November 1, 2023. ⤶

- ”Maryland Insurance Administration Approves 2024 Affordable Care Act Premium Rates” Maryland Insurance Administration, September 18, 2023. ⤶

- “Modest Premium Changes Ahead in Health Insurance Marketplaces in Washington State and Maryland“ The Commonwealth Fund, October 20, 2014. ⤶

- “Maryland: *Approved* 2016 Weighted Avg. Hikes: 20.0% Overall (Updated)“ ACA Signups. September 4, 2015. ⤶

- “Maryland: *Approved* 2017 Avg. Rate Hikes Revised: 25.2% Vs. 27.9% Requested“ ACA Signups. September 24, 2016. ⤶

- “2018 Rate Hikes“ ACA Signups. ⤶

- “Marylanders to see premiums drop 13% on average for 2019 ACA plans” Baltimore Business Journal. September 21, 2018. ⤶

- “Maryland: *Approved* 2020 ACA Exchange Premium Rate Changes: 10.3% Reduction“ ACA Signups. September 19, 2019. ⤶

- “2021 ACA Approved Health Insurance Rates Individual Non-Medigap & Small Group Markets“ Maryland Insurance Administration. September 21, 2020. ⤶

- “Maryland Insurance Administration Approves 2022 Affordable Care Act Premium Rates“ Maryland Insurance Administration. September 3, 2021. ⤶

- “Maryland Insurance Administration Approves 2023 Affordable Care Act Premium Rates“ Maryland Insurance Administration. September 16, 2022. ⤶

- “Exhibit 1: 2024 Maryland ACA Individual Market Rate Filing Summary“ Maryland Insurance Administration, insurance.maryland.gov, September 2023. ⤶

- ”70,000 Marylanders May Lose Health Coverage If Proposed Bill Passes” Maryland Health Connection. June 3, 2025 ⤶

- “ASPE Issue Brief (2014)” ASPE, 2015 ⤶

- ”Health Insurance Marketplaces 2015 Open Enrollment Period: March Enrollment Report”, HHS.gov, 2015 ⤶

- “HEALTH INSURANCE MARKETPLACES 2016 OPEN ENROLLMENT PERIOD: FINAL ENROLLMENT REPORT” HHS.gov, 2016 ⤶

- “2017 Marketplace Open Enrollment Period Public Use Files” CMS.gov, 2017 ⤶

- “2018 Marketplace Open Enrollment Period Public Use Files” CMS.gov, 2018 ⤶

- “2019 Marketplace Open Enrollment Period Public Use Files” CMS.gov, 2019 ⤶

- “2020 Marketplace Open Enrollment Period Public Use Files” CMS.gov, 2020 ⤶

- “2021 Marketplace Open Enrollment Period Public Use Files” CMS.gov, 2021 ⤶

- “2022 Marketplace Open Enrollment Period Public Use Files” CMS.gov, 2022 ⤶

- “2023 Marketplace Open Enrollment Period Public Use Files” CMS.gov, March 2023 ⤶

- ”HEALTH INSURANCE MARKETPLACES 2024 OPEN ENROLLMENT REPORT” CMS.gov, 2024 ⤶

- “2025 Marketplace Open Enrollment Period Public Use Files” CMS.gov, May 2025 ⤶

- ”State-based Marketplace (SBM) Medicaid Unwinding Report” Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Data through September 2024. ⤶

- ”Nearly 215,000 Enroll in 2024 Coverage, Most Ever for Maryland Health Connection” Maryland Health Connection. January 18, 2024. ⤶