Home > Health insurance Marketplace > Montana

Montana Marketplace health insurance in 2025

Compare ACA plans and check subsidy savings from a third-party insurance agency.

Montana health insurance Marketplace guide

We’ve created this guide, including the FAQs below, to help you understand the health insurance options available to you and your family in Montana. An ACA Marketplace (exchange) plan – or Obamacare – is a good option for people who need to buy their own individual or family health coverage. This includes people who aren’t eligible for Medicaid, Medicare, or an affordable plan offered by an employer.

Montana uses the federally-facilitated Marketplace, which is HealthCare.gov. Three private insurance companies offer coverage in the Montana Health Insurance Marketplace.3 And unlike many states where coverage areas vary from one carrier to another, all three insurers offer Marketplace coverage statewide in Montana.4

Income-based subsidies are available through the Montana Marketplace: Most enrollees qualify for premium subsidies, and many also qualify for subsidies that reduce out-of-pocket medical costs.5

If the Marketplace determines that you or your kids are likely eligible for Medicaid or CHIP (Healthy Montana Kids), they will refer you to Montana Medicaid/CHIP.

Frequently asked questions about health insurance in Montana

Who can buy Marketplace health insurance?

To enroll in private health coverage through Montana’s Marketplace (HealthCare.gov), you must:6

- Live in Montana and be lawfully present in the United States

- Not be incarcerated

- Not have Medicare coverage

So most people are eligible to enroll in Marketplace coverage. But qualifying for financial assistance (premium subsidies and cost-sharing reductions) is a bit more complex. Eligibility for financial assistance depends on your income, and you must also:

- Not have access to affordable health coverage offered by an employer. If you’re eligible to enroll in an employer-sponsored plan but it seems too expensive, you can use our Employer Health Plan Affordability Calculator to see if you might qualify for premium subsidies in the Marketplace.

- Not be eligible for Medicaid or CHIP (Montana Healthy Kids).

- Not be eligible for premium-free Medicare Part A.7

- If married, file a joint tax return with your spouse.8

- Not be able to be claimed by someone else as a tax dependent.8

When can I enroll in an ACA-compliant plan in Montana?

You can sign up for an ACA-compliant individual or family health plan in Montana during the annual open enrollment period, which runs from November 1 through January 15.

For coverage to take effect on January 1, you must complete your enrollment by December 15. If your application is submitted between December 16 and January 15, your coverage will take effect on February 1.6

Once the open enrollment window ends, you may still be eligible to enroll or make a plan change if you experience a qualifying life event, such as giving birth or losing other health coverage. Some people can enroll year-round even without a specific qualifying event.

Enrollment in Montana Medicaid and Healthy Montana Kids (CHIP) is available year-round.9 If you’re eligible for either program, you can enroll anytime.

How do I enroll in a Marketplace plan in Montana?

To enroll in an ACA Marketplace (exchange) plan in Montana, you can:

- Visit HealthCare.gov, which is Montana’s Marketplace (exchange). This platform lets Montana residents comparison shop for health coverage, determine subsidy eligibility, and select the plan that best meets their needs.

- Enroll in Marketplace coverage with the help of an insurance agent or broker, or a Navigator or certified application counselor.

- Enroll via an approved enhanced direct enrollment entity (EDE).10 (EDEs can also offer off-exchange plans and non-ACA-compliant plans, so be sure to specify that you want to enroll in Marketplace/exchange coverage, as that’s the only way to obtain any subsidies for which you might be eligible.)

You can also call HealthCare.gov’s contact center by dialing 1-800-318-2596 (TTY: 1-855-889-4325). The call center is available 24 hours a day, seven days a week, except for holidays.

How can I find affordable health insurance in Montana?

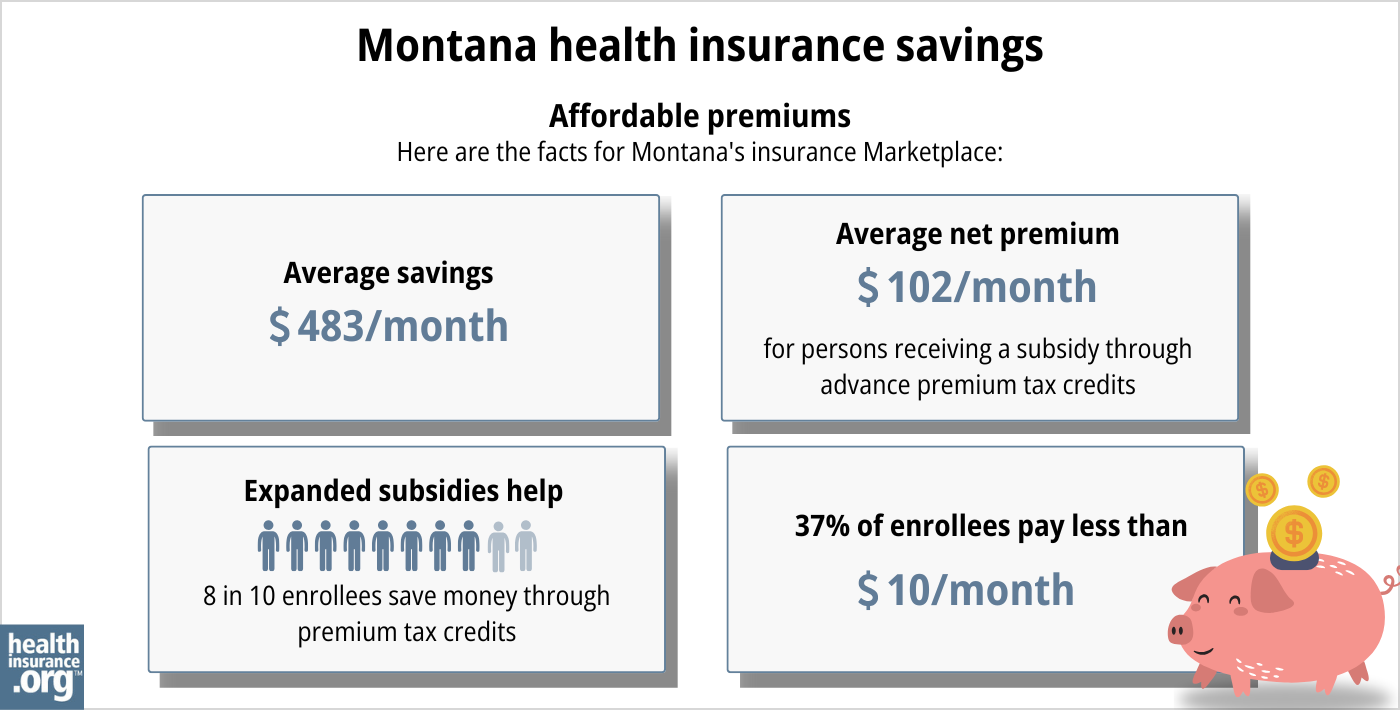

You may find affordable health insurance coverage in Montana by enrolling through HealthCare.gov. This is especially true if you qualify for subsidies, and most enrollees in Montana are subsidy-eligible.

The Affordable Care Act created income-based premium subsidies called Advance Premium Tax Credits (APTC).11 If you’re eligible for APTC, it will reduce the amount you owe in premiums each month – sometimes even to $0, depending on your income and the plan you select.

Eighty-nine percent of Montana’s Marketplace enrollees were receiving premium subsidies as of early 2024. These subsidies paid an average of $505/month, reducing the average enrollee’s premium to about $156/month (including those who paid full price).12

In addition to premium subsidies, you may also qualify for cost-sharing reductions (CSR) if your household income isn’t more than 250% of the federal poverty level. CSR subsidies will make the deductible and other out-of-pocket expenses (for a Silver-level plan) smaller than they would otherwise be. Thirty percent of Montana’s Marketplace enrollees were receiving CSR benefits in 2024.12

You can combine APTC and CSR benefits if you’re eligible for both, as long as you select a Silver-level plan (APTC can be used with plans at any metal level, but CSR benefits are only available on Silver plans).

Source: CMS.gov13

Montana implemented a reinsurance program in 2020, which resulted in overall average rate decreases that year and relatively flat rates the following year.14 So if you’re not eligible for premium subsidies in Montana, the reinsurance program does ensure that your premiums are lower than they would otherwise be.

Depending on your income and circumstances, you may find that you’re eligible for free or low-cost health coverage through Montana Medicaid or Healthy Montana Kids (CHIP). Check to see if you meet the criteria for these programs in Montana.

How many insurers offer Marketplace coverage in Montana?

Three private insurance companies offer Marketplace health insurance coverage in Montana,15 and all three have statewide coverage areas.4

One of Montana’s insurers, Montana/Mountain Health CO-OP, is among just three ACA-created CO-OPs still in operation nationwide.

Are Marketplace health insurance premiums increasing in Montana?

The following average premium changes were approved for 2025 for the insurers that offer individual/family health insurance in Montana.16

Montana’s ACA Marketplace Plan 2025 APPROVED Rate Increases by Insurance Company |

|

|---|---|

| Issuer | Percent Increase |

| BCBS of Montana (Health Care Service Corporation, or HCSC) | 5.03% |

| Montana Health CO-OP | 13.4% |

| PacificSource | 8.16% |

Source: Federal rate review database17

Average rate increases are for full-price plans. But 89% of Marketplace enrollees in Montana receive premium tax credits that cover some or all of their monthly premium costs.12

These subsidies are adjusted each year to match changes in the benchmark plan (the second-lowest-cost Silver plan) in each area. As a result of the American Rescue Plan and the Inflation Reduction Act, subsidies are larger and more widely available than they were in the past, and that will continue to be true at least through 2025.18

For perspective, here’s an overview of how average full-price premiums have changed in Montana’s individual/family health insurance market over the years:

- 2015: Average increase of 3%.19

- 2016: Average increase of 25.9%.20

- 2017: Average increase of 47.6%.21

- 2018: Average increase of 19.5%.22

- 2019: Average increase of 5.7%.23

- 2020: Average decrease of 13.1%.24 (reinsurance program took effect)

- 2021: Average increase of 1.4%.25

- 2022: Average increase of 0.5%.26

- 2023: Average increase of 9.6%.27

- 2024: Average increase of 4.9%28

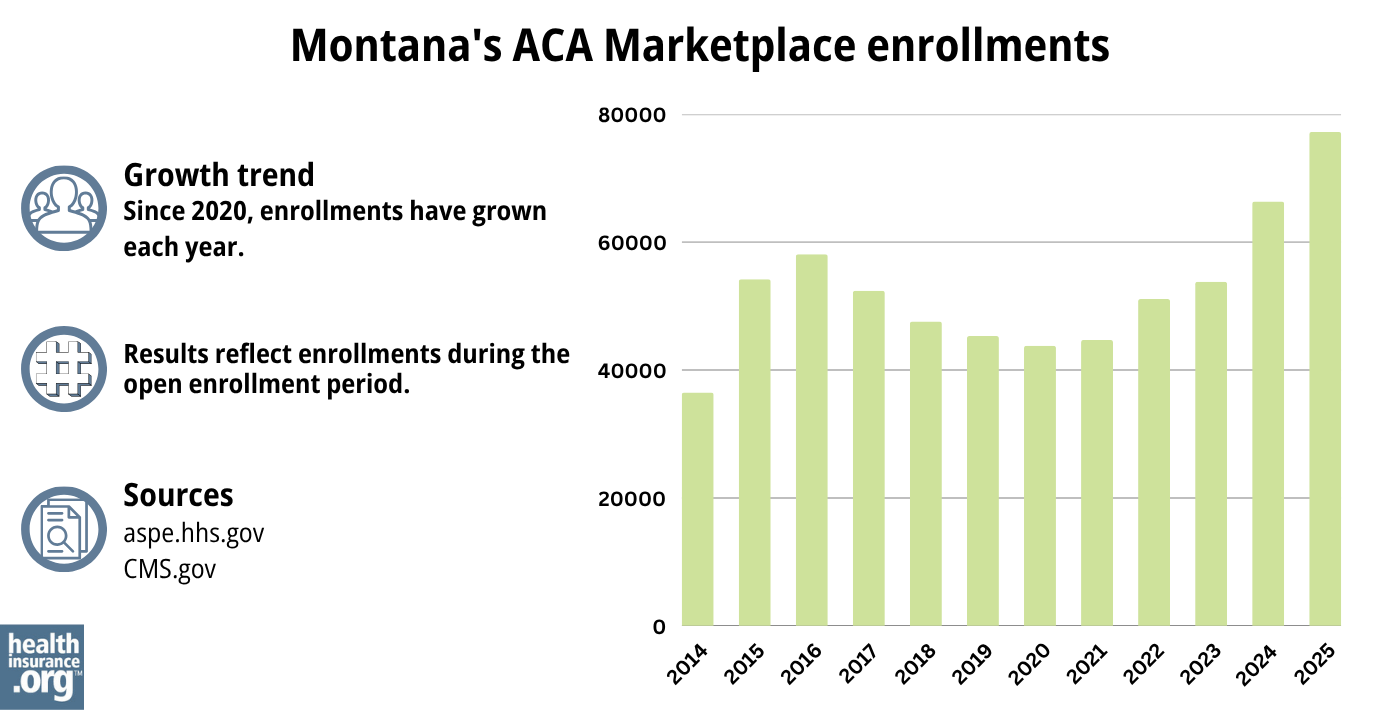

How many people are insured through the Marketplace in Montana?

What health insurance resources are available to Montana residents?

HealthCare.gov

The Marketplace in Montana, where residents can enroll in individual/family health coverage and receive income-based subsidies. You can reach HealthCare.gov at 800-318-2596.

Montana Commissioner of Securities and Insurance

Licenses and regulates health insurance companies, agents, and brokers; can provide assistance to consumers who have questions or complaints about entities the Commissioner regulates.

Montana Primary Care Association

Montana’s federally funded Navigator organization

Montana State Health Insurance Assistance Program

A local service that provides assistance and enrollment counseling for Medicare beneficiaries and their caregivers.

Montana Medicaid and Healthy Montana Kids

(Montana’s Children’s Health Insurance Program)

Louise Norris is an individual health insurance broker who has been writing about health insurance and health reform since 2006. She has written dozens of opinions and educational pieces about the Affordable Care Act for healthinsurance.org.

Looking for more information about other options in your state?

Need help navigating health insurance options in Montana?

Explore more resources for options in Montana including short-term health insurance, dental insurance, Medicaid and Medicare.

Speak to a sales agent at a licensed insurance agency.

Footnotes

- ”2025 OEP State-Level Public Use File (ZIP)” Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Accessed May 13, 2025 ⤶ ⤶

- ”Rate Review Submissions” RateReview.HealthCare.gov. Accessed Jan. 7, 2025 ⤶

- “Montana Rate Review Submissions” HealthCare.gov, Accessed Aug. 1, 2024 ⤶

- Plan Year 2025 Qualified Health Plan Choice and Premiums in HealthCare.gov Marketplaces. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. October 25, 2024 ⤶ ⤶

- 2024 Marketplace Open Enrollment Period Public Use Files. CMS.gov, Accessed Sep. 15, 2024 ⤶

- “A quick guide to the Health Insurance Marketplace®” HealthCare.gov, Accessed August, 2023 ⤶ ⤶

- Medicare and the Marketplace, Master FAQ. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Accessed November 2023. ⤶

- Premium Tax Credit — The Basics. Internal Revenue Service. Accessed MONTH. ⤶ ⤶

- “Montana Medicaid and Healthy Montana Kids (HMK) Plus” Montana.gov, Accessed September 2023 ⤶

- “Entities Approved to Use Enhanced Direct Enrollment” CMS.gov, April 28, 2023 ⤶

- “APTC and CSR Basics” CMS.gov, June 2024 ⤶

- ”Effectuated Enrollment: Early 2024 Snapshot and Full Year 2023 Average” CMS.gov, July 2, 2024 ⤶ ⤶ ⤶

- “2025 Marketplace Open Enrollment Period Public Use Files” CMS.gov, May 2025 ⤶

- Montana Individual Health Reinsurance. Montana Reinsurance Association. Accessed December 2023. ⤶

- “Montana Rate Review Submissions” HealthCare.gov. Accessed Oct. 15, 2024 ⤶

- “Montana Rate Review Submissions” RateReview.HealthCare.gov, Accessed Nov. 1, 2024 ⤶

- “Montana Rate Review Submissions” RateReview.HealthCare.gov, Accessed Nov. 1, 2024 ⤶

- “Health Insurance Marketplaces 2023 Open Enrollment Report” CMS.gov, 2023 ⤶

- Analysis Finds No Nationwide Increase in Health Insurance Marketplace Premiums. The Commonwealth Fund. December 2014. ⤶

- FINAL PROJECTION: 2016 Weighted Avg. Rate Increases: 12-13% Nationally* ACA Signups. October 2015. ⤶

- Avg. UNSUBSIDIZED Indy Mkt Rate Hikes: 25% (49 States + DC). ACA Signups. October 2016. ⤶

- 2018 Rate Hikes. ACA Signups. October 2017. ⤶

- 2019 Rate Hikes. ACA Signups. October 2018. ⤶

- 2020 Rate Changes. ACA Signups. October 2019. ⤶

- 2021 Rate Changes. ACA Signups. October 2020. ⤶

- 2022 Rate Changes. ACA Signups. October 2021. ⤶

- “Montana: Final Avg. Unsubsidized 2023 #ACA Rate Change: +9.6% (Up From +8.9%)” ACASignups.net, Oct. 12, 2022 ⤶

- So How’d I Do On My 2024 Avg. Rate Change Project? Not Bad At All! ACA Signups. December 2023. ⤶

- ”Health Insurance Marketplaces 2024 Open Enrollment Period Report” CMS.gov. March 22, 2024 ⤶

- “ASPE Issue Brief (2014)” ASPE, 2015 ⤶

- “Health Insurance Marketplaces 2015 Open Enrollment Period: March Enrollment Report”, HHS.gov, 2015 ⤶

- “HEALTH INSURANCE MARKETPLACES 2016 OPEN ENROLLMENT PERIOD: FINAL ENROLLMENT REPORT” HHS.gov, 2016 ⤶

- “2017 Marketplace Open Enrollment Period Public Use Files” CMS.gov, 2017 ⤶

- “2018 Marketplace Open Enrollment Period Public Use Files” CMS.gov, 2018 ⤶

- “2019 Marketplace Open Enrollment Period Public Use Files” CMS.gov, 2019 ⤶

- “2020 Marketplace Open Enrollment Period Public Use Files” CMS.gov, 2020 ⤶

- “2021 Marketplace Open Enrollment Period Public Use Files” CMS.gov, 2021 ⤶

- “2022 Marketplace Open Enrollment Period Public Use Files” CMS.gov, 2022 ⤶

- “Health Insurance Marketplaces 2023 Open Enrollment Report” CMS.gov, Accessed August 2023 ⤶

- ”HEALTH INSURANCE MARKETPLACES 2024 OPEN ENROLLMENT REPORT” CMS.gov, 2024 ⤶

- “2025 Marketplace Open Enrollment Period Public Use Files” CMS.gov, May 2025 ⤶