Home > Health insurance Marketplace > Tennessee

Tennessee Marketplace health insurance in 2025

Compare ACA plans and check subsidy savings from a third-party insurance agency.

Tennessee health insurance Marketplace guide

This guide, including the FAQs below, was developed to assist you in choosing the right Tennessee health insurance plan for you and your family. The options found in Tennessee’s ACA Marketplace may be a good choice for many consumers, and we will guide you through the options below.

Tennessee uses the federally-facilitated health insurance exchange (Marketplace), HealthCare.gov, for residents to purchase its ACA Marketplace plans. The Tennessee Marketplace provides access to health insurance products from six private insurers,3 although plan availability varies from one area of the state to another. And there are some changes for 2025, with one exiting insurer and one new insurer (details below).

When you enroll in a plan through the Marketplace, you may find that you’re eligible for financial assistance that reduces the monthly cost of your coverage (premium subsidies), and possibly also your out-of-pocket expenses (cost-sharing reductions, or CSR). These are federal subsidy programs created by the Affordable Care Act, and eligibility depends on your income and circumstances.

Frequently asked questions about health insurance in Tennessee

Who can buy Marketplace health insurance?

To qualify for health coverage through the Tennessee Marketplace, you must:4

- Live in Tennessee

- Be lawfully present in the United States

- Not be incarcerated

- Not be enrolled in Medicare

Eligibility for financial assistance (premium subsidies and cost-sharing reductions) depends on your income. In addition, to qualify for financial assistance with your Marketplace plan you must:

- Not have access to affordable employer-sponsored health insurance. If your employer offers coverage but you feel it’s too expensive, you can use our Employer Health Plan Affordability Calculator to see if you might qualify for premium subsidies in the Marketplace.

- Not be eligible for Medicaid or CHIP.

- Not be eligible for premium-free Medicare Part A.5

- Not be able to be claimed by someone else as a tax dependent.6

- If you’re married, you must file a joint tax return with your spouse.7 (with very limited exceptions)8

When can I enroll in an ACA-compliant plan in Tennessee?

In Tennessee, the open enrollment period for individual/family health coverage runs from November 1 to January 15.9

If you need your coverage to start on January 1, you must apply by December 15. If you apply between December 16 and January 15, your coverage will begin on February 1.10

Outside of open enrollment, a special enrollment period (typically triggered by a specific qualifying life event) is necessary to enroll or make changes to your coverage.

If you have questions about open enrollment, you can learn more in our comprehensive guide to open enrollment. We also have a comprehensive guide to special enrollment periods.

How do I enroll in a Tennessee Marketplace plan?

To enroll in an ACA Marketplace plan in Tennessee, you can:

- Visit HealthCare.gov to access Tennessee’s health insurance marketplace. Here you will find an online platform to shop, compare, and choose the best health plans.

- Purchase individual and family health coverage with the help of an insurance agent or broker, a Navigator or certified application counselor, or an approved enhanced direct enrollment entity.11

You can also call HealthCare.gov’s contact center by dialing 1-800-318-2596 (TTY: 1-855-889-4325). The call center is available 24 hours a day, seven days a week, but it’s closed on holidays.

How can I find affordable health insurance in Tennessee?

Tennessee uses the federally-facilitated exchange for individual market plans, so residents who buy their own health insurance enroll through HealthCare.gov.

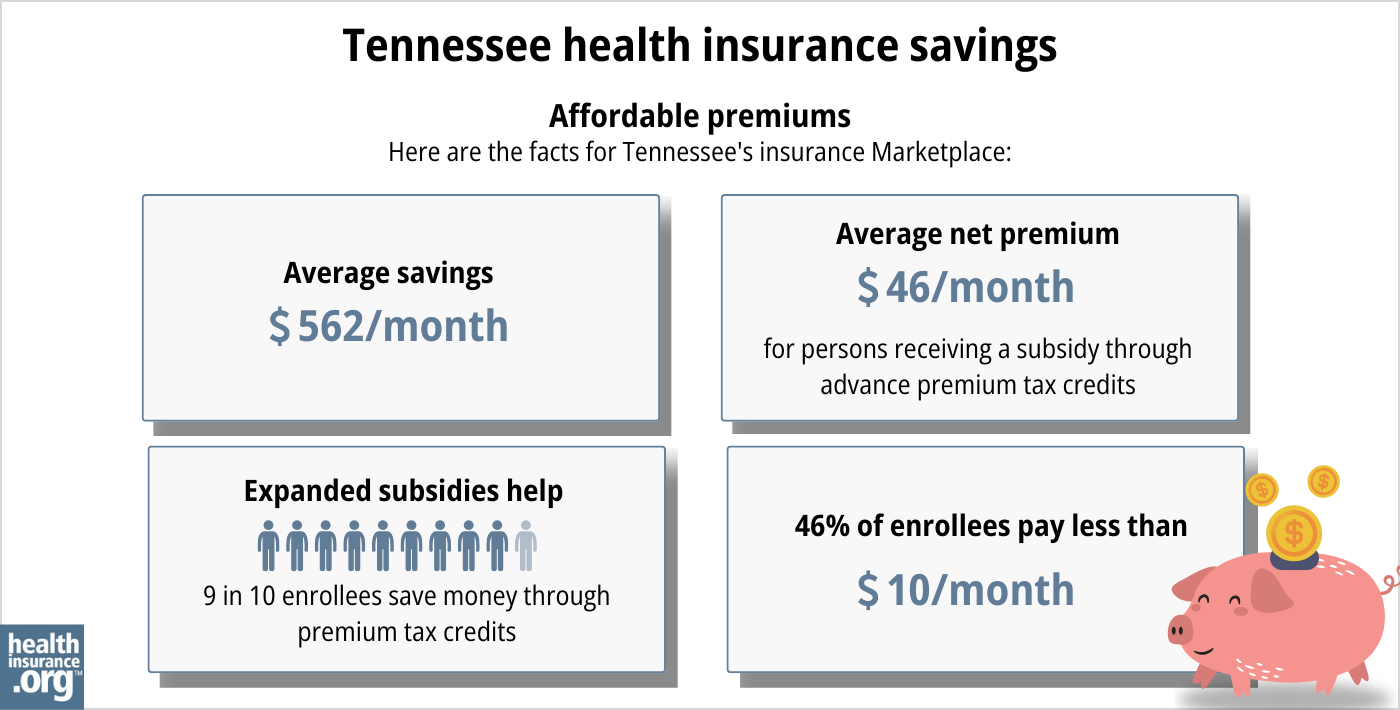

Ninety-six percent of the people who purchased health plans through the Tennessee Marketplace in 2024 were eligible for advance premium tax credits (APTC), also known as premium subsidies. The APTC amounted to an average savings of $581/month and reduced the average enrollee’s premium to about $66/month.12

Marketplace enrollees with household incomes of no more than 250% of the federal poverty level also qualify for cost-sharing reductions (CSR) that will result in lower deductibles and out-of-pocket expenses for Silver plans (these cost-sharing reductions are not available on plans at other metal levels).13 Between the premium subsidies and cost-sharing reductions, you may find that a Tennessee Marketplace health insurance plan provides the best value.

Source: CMS.gov14

Tennessee has a coverage gap because the state has refused to expand Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act. Childless adults without disabilities are ineligible for Tennessee Medicaid regardless of how low their income is. Because the ACA’s premium tax credits (subsidies) aren’t available to applicants with income below the poverty level (because the law called for them to have expanded Medicaid instead), these applicants fall into what’s come to be known as a coverage gap. They are ineligible for Medicaid and also ineligible for premium tax credits to make private coverage more affordable.

There are an estimated 95,000 Tennessee residents in the coverage gap.15

How many insurers offer Marketplace coverage in Tennessee?

For 2025 coverage, six insurers offer individual/family health plans through the exchange/Marketplace in Tennessee.3

The number of participating insurers is unchanged from 2024, but there is one new insurer (Alliant Health Plans),3 and one carrier that is exiting the market at the end of 2024 (Ascension/US Health & Life).16 Tennessee residents enrolled in Ascension plans in 2024 will need to pick new coverage during the open enrollment period for 2025, which began November 1, 2024. As long as these enrollees select a replacement plan by December 31, it will take effect on January 1, 2025.

Plan availability varies from one part of the state to another, but all areas of Tennessee have at least three participating exchange-based health insurers offering plans for 2025.17

Are Marketplace health insurance premiums increasing in Tennessee?

For 2025, the following average rate changes were approved for Tennessee’s individual/family insurers (before subsidies are applied):3

Tennessee’s ACA Marketplace Plan 2025 APPROVED Rate Increases by Insurance Company |

|

|---|---|

| Issuer | Percent Increase |

| Blue Cross Blue Shield of Tennessee | -0.98% |

| Cigna | 2.99% |

| Oscar | 3.86% |

| Celtic/Ambetter | 2.3% |

| UnitedHealthcare | -1.26% |

| Alliant Health Plans | new to the market |

| US Health and Life/Ascension | exiting market |

Source: Tennessee Department of Commerce and Insurance3

Tennessee no longer has an effective rate review program, so the federal government (CMS) reviews the rates that are filed in Tennessee.18

The average approved rate changes listed above are calculated before any subsidies are applied. The majority of Tennessee’s Marketplace enrollees do receive subsidies, which change each year to keep pace with the cost of the second-lowest-cost Silver plan in each area.

For perspective, here’s an overview of how full-price (unsubsidized) average premiums have changed in Tennessee over the years:

- 2015: Average increase of 9%.19

- 2016: Average increase of 28.2%.20

- 2017: Average increase of 56%.21

- 2018: Average increase of 28.5%.22

- 2019: Average decrease of 12.4%.23

- 2020: Average decrease of 1.1%.24

- 2021: Average increase of 8.2%25

- 2022: Average increase of 4.4%.26

- 2023: Average increase of 8.5%.27

- 2024: Average increase of 4.8%.28

How many people are insured through Tennessee’s Marketplace?

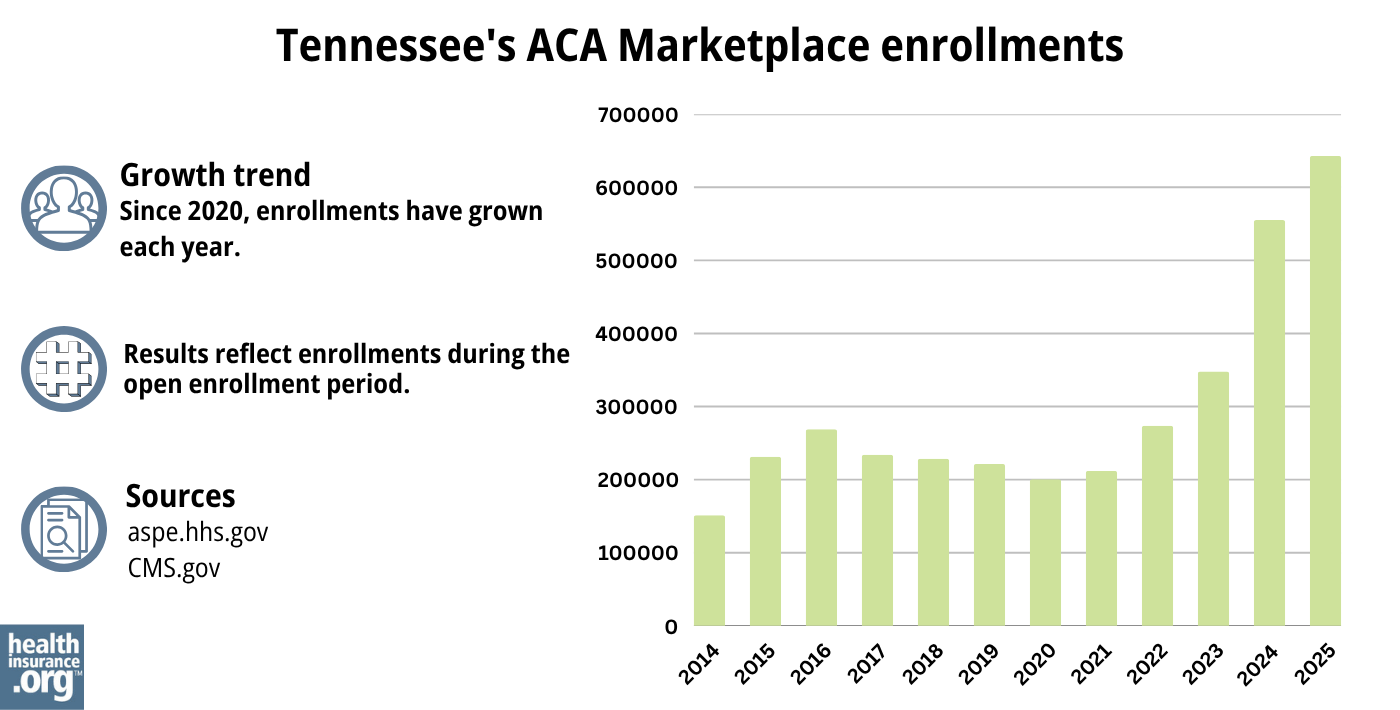

A significant record-high of more than 555,000 people enrolled in private health coverage through the Tennessee exchange during the open enrollment period for 2024 coverage.29 The previous record high had been fewer than 350,000 people, set the year before.30 (See chart below for a summary of enrollment by year.)

The surge in enrollment in recent years is due in part to the American Rescue Plan (ARP) making ACA’s premium subsidies more substantial. Under the ARP’s subsidy enhancement rules – now extended through 2025 by the Inflation Reduction Act – subsidies are larger and more widely available than they used to be.30

The enrollment growth for 2024 was also due in part to the “unwinding” of the COVID-related Medicaid continuous coverage rule (people were not disenrolled from Medicaid for three years during the pandemic, but that ended in the spring of 2023). By April 2024, nearly 124,000 Tennessee residents had transitioned from Medicaid or CHIP to a private Marketplace plan.31

Source: 2014,32 2015,33 2016,34 2017,35 2018,36 2019,37 2020,38 2021,39 2022,40 2023,41 2024,42 202543

What health insurance resources are available to Tennessee residents?

HealthCare.gov

800-318-2596

State Exchange Profile: Tennessee

The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation overview of Tennessee’s progress toward creating a state health insurance exchange.

Louise Norris is an individual health insurance broker who has been writing about health insurance and health reform since 2006. She has written dozens of opinions and educational pieces about the Affordable Care Act for healthinsurance.org.

Looking for more information about other options in your state?

Need help navigating health insurance options in Tennessee?

Explore more resources for options in Tennessee including short-term health insurance, dental insurance, Medicaid and Medicare.

Speak to a sales agent at a licensed insurance agency.

Footnotes

- ”2025 OEP State-Level Public Use File (ZIP)” Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Accessed May 13, 2025 ⤶ ⤶

- ”Rate Review Submissions” RateReview.HealthCare.gov. Accessed Jan. 7, 2025 ⤶

- ”TDCI Offers Consumer Insurance Tips for 2025 ACA Open Enrollment” Tennessee Department of Commerce and Insurance. October 31, 2024. ⤶ ⤶ ⤶ ⤶ ⤶

- ”A quick guide to the Health Insurance Marketplace” HealthCare.gov ⤶

- Medicare and the Marketplace, Master FAQ. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Accessed November 12, 2023. ⤶

- Premium Tax Credit — The Basics. Internal Revenue Service. Accessed January 12, 2024. ⤶

- Premium Tax Credit — The Basics. Internal Revenue Service. Accessed MONTH. ⤶

- Updates to frequently asked questions about the Premium Tax Credit. Internal Revenue Service. February 2024. ⤶

- “When can you get health insurance?” HealthCare.gov, 2023 ⤶

- “A quick guide to the Health Insurance Marketplace®” HealthCare.gov, Accessed August, 2023 ⤶

- “Entities Approved to Use Enhanced Direct Enrollment” CMS.gov, April 28, 2023 ⤶

- ”Effectuated Enrollment: Early 2024 Snapshot and Full Year 2023 Average” CMS.gov, July 2, 2024 ⤶

- ”APTC and CSR Basics” Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Accessed February 15, 2024. ⤶

- “2025 Marketplace Open Enrollment Period Public Use Files” CMS.gov, May 2025 ⤶

- How Many Uninsured Are in the Coverage Gap and How Many Could be Eligible if All States Adopted the Medicaid Expansion? KFF. March 2023. ⤶

- ”SERFF Filing USHL-134096338” SERFF. May 21, 2024 ⤶

- Plan Year 2025 Qualified Health Plan Choice and Premiums in HealthCare.gov Marketplaces. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. October 25, 2024 ⤶

- ”State Effective Rate Review Programs” CMS.gov. Accessed Nov. 19, 2024 ⤶

- Analysis Finds No Nationwide Increase in Health Insurance Marketplace Premiums. The Commonwealth Fund. December 2014. ⤶

- FINAL PROJECTION: 2016 Weighted Avg. Rate Increases: 12-13% Nationally* ACA Signups. October 2015. ⤶

- 2017 Rate Project State Roundup: IN, IA, ME, MA, MT, ND, SD, TN. ACA Signups. September 2016. ⤶

- 2018 Rate Hikes. ACA Signups. October 2017. ⤶

- Tennessee: Correction Re. Final 2019 #ACA Rate Changes: 12.4% DROP (Vs. ~22% Drop W/Out #ACASabotage). ACA Signups. October 2018. ⤶

- Tennessee: APPROVED Avg. 2020 #ACA Premiums: 1.1% DECREASE; 3 Carriers Expanding Coverage. ACA Signups. August 2019. ⤶

- Weighted average calculated by healthinsurance.org, using these sources: TDCI Approves Health Insurance Carriers’ Rates on the Federally Facilitated Marketplace for 2021. Tennessee Department of Commerce and Insurance. September 2020. And Tennessee: Preliminary Avg. 2021 #ACA Premiums: +5.0% Indy Market, +5.5% Sm. Group. ACA Signups. July 2020. ⤶

- Tennessee: Approved Avg. 2022 #ACA Rate Changes: +4.4% Indy Market; +8.9% Sm. Group (Updated). ACA Signups. October 2021. ⤶

- Tennessee: Final Avg. Unsubsidized 2023 #ACA Rate Changes: +8.5%. ACA Signups. October 2022. ⤶

- Tennessee: *Final* Avg. Unsubsidized 2024 #ACA Rate Changes: +4.8%. ACA Signups. September 2, 2023. ⤶

- ”Marketplace 2024 Open Enrollment Period Report: Final National Snapshot” Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. January 24, 2024. ⤶

- “Health Insurance Marketplaces 2023 Open Enrollment Report” CMS.gov, 2023 ⤶ ⤶

- ”HealthCare.gov Marketplace Medicaid Unwinding Report” Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Data through April 2024; Accessed Aug. 2, 2024 ⤶

- “ASPE Issue Brief (2014)” ASPE, 2015 ⤶

- “Health Insurance Marketplaces 2015 Open Enrollment Period: March Enrollment Report” HHS.gov, 2015 ⤶

- “Health Insurance Marketplaces 2016 Open Enrollment Period: Final Enrollment Report” HHS.gov, 2016 ⤶

- “2017 Marketplace Open Enrollment Period Public Use Files” CMS.gov, 2017 ⤶

- “2018 Marketplace Open Enrollment Period Public Use Files” CMS.gov, 2018 ⤶

- “2019 Marketplace Open Enrollment Period Public Use Files” CMS.gov, 2019 ⤶

- “2020 Marketplace Open Enrollment Period Public Use Files” CMS.gov, 2020 ⤶

- “2021 Marketplace Open Enrollment Period Public Use Files” CMS.gov, 2021 ⤶

- “2022 Marketplace Open Enrollment Period Public Use Files” CMS.gov, 2022 ⤶

- “2023 Marketplace Open Enrollment Period Public Use Files” CMS.gov, 2023 ⤶

- ”HEALTH INSURANCE MARKETPLACES 2024 OPEN ENROLLMENT REPORT” CMS.gov, 2024 ⤶

- “2025 Marketplace Open Enrollment Period Public Use Files” CMS.gov, May 2025 ⤶