One of the single most far-reaching cutbacks of the Senate repeal bill will be targeted at individuals who earn no more than $16,643 a year*.

That's right. The GOP – in both the Senate and House version of legislation to repeal and replace the Affordable Care Act – aims to undo coverage gains for Americans who benefited from the ACA's Medicaid expansion. More specifically, that means people with household incomes of 138 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL) or less – in states that accepted the expansion.

Don't think 138%. Think $320 a week.

Sadly, media references to assistance for folks who earn up to "138 percent of FPL," are probably not "jaw-droppers" for an American population that's typically uninformed about health policy's implications. It's only when you break it down – revealing that 138 percent of FPL means "earning $320 a week or less" – that people can grasp stark reality.

Let that sink in for a second. The GOP's repeal legislation is saying that Americans who earn less than $46 a day are undeserving of financial help in paying for health coverage.

What argument could possibly convince critics of the Medicaid expansion that taking back health coverage from someone who earns $46 dollars a day – or less – is the right thing to do? One of the oldest and oft-used arguments is that these individuals and families are undeserving because they're able-bodied and not working.

(And that's really putting the accusation in the most polite of terms. More often, the finger pointing involves words like "freeloaders" or "free-riders" or words much more derogatory.)

Bu regardless of how the argument is used, it's a flawed argument.

How many are actually 'not working?'

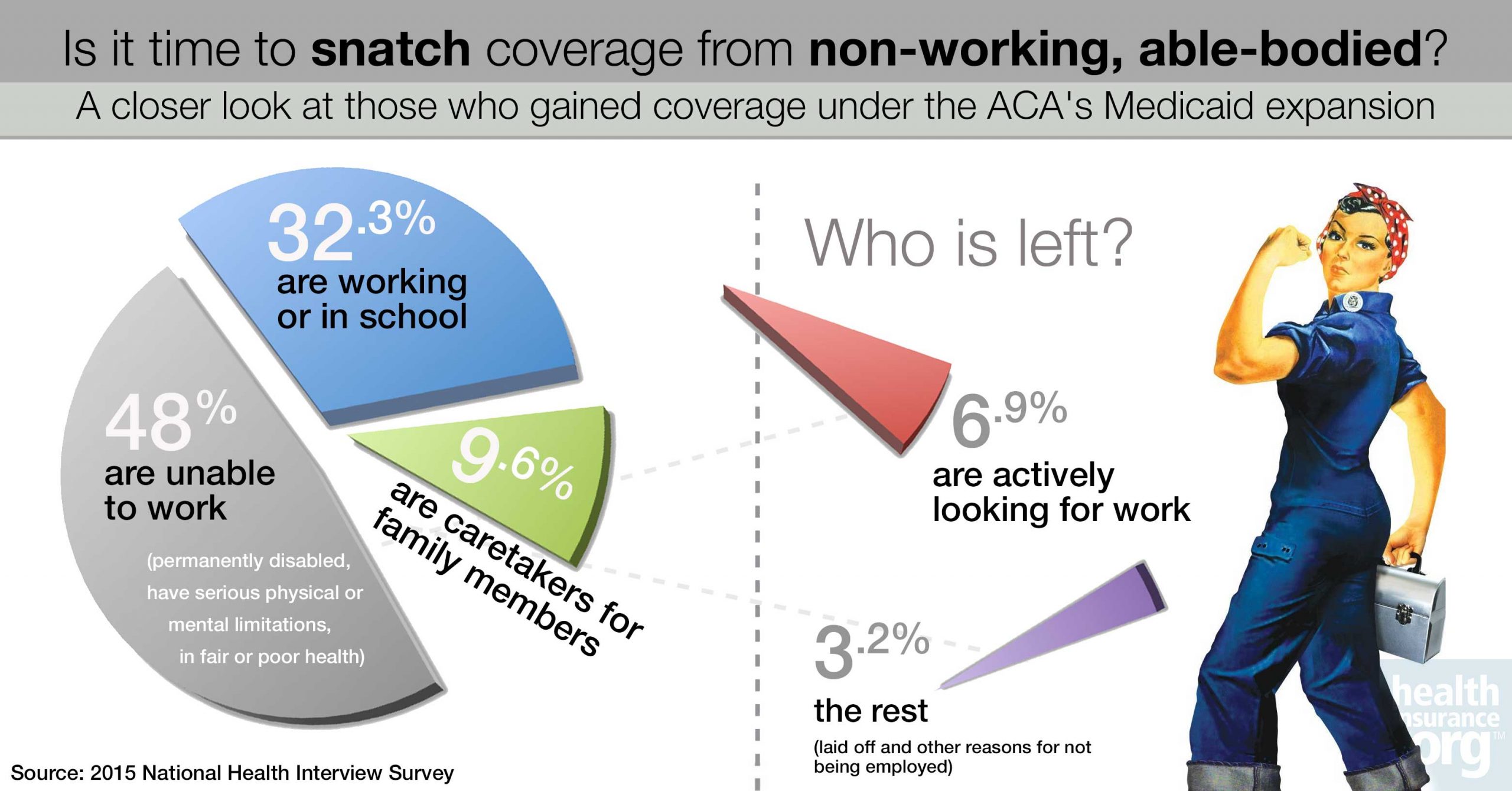

Recent research shows that of the expansion population, there's only a tiny fraction of the population that fits the definition of "able-bodied" and "not working." How tiny? About 3.2 percent.

For starters, almost half of those Americans who gained coverage through the expansion – 48 percent of them – aren't even "able-bodied." According to researchers at The George Washington University's Center for Health Policy Research, citing findings from the 2015 National Health Interview Survey, the adults in that huge segment of the expansion population are "permanently disabled, have serious physical or mental limitations – caused by conditions like cancer, stroke, heart disease, cognitive or mental health disorders, arthritis, pregnancy, or diabetes – or are in fair or poor health."

That leaves about 52 percent of the beneficiaries who can be described as "able-bodied." But here's the thing: of those folks, 62 percent (actually 32.3 percent of the total expansion population) are already working or going to school (which – hello – is working). Another 13** percent of those able-bodied (almost 7 percent of the expansion population) are looking for work. (And again, if you've looked for work recently, you know that looking is actually work.) But the point is, they want to work.

So what about the rest of the able-bodied – about one-fourth of that group (able-bodied but not working and not in school)? They don't have jobs. They're not in school. They're not looking for jobs. What could they possibly be up to?

Turns out that three-quarters of that group (or about 9.6 percent of the expansion population) are not employed because they're taking care of family members. Are they really "not working?" (Have you taken care of a family member? Did that seem like "not working" to you?) The answer is that yes, they are also working.

The 3.2 percent

That leaves us with the remaining one-fourth of the able-bodied (or 3.2 percent of the expansion population) who are not working.

Should we assume that these people are able-bodied but just don't want to work? Probably not, since some of them list "laid off" as a reason – which says they had been working and thus wanted to work.

Can we assume that all of them want to work? I wouldn't go that far either.

But let's say we do go that far – and we let ourselves believe that the full 3.2 percent were "milking the system." Further, let's hypothesize that some of the aforementioned 7 percent who say they're looking for work actually aren't, for whatever reason. What then? We're still looking at a small slice of the Medicaid expansion population that consistently is held up as evidence that the expansion was some kind of "handout" and that the expansion population is somehow unworthy of financial assistance.

There's a troubling conclusion that we can and should draw from these statistics, but it's not that we should be distracted by the delusion that low-income Americans are being coddled and given disincentives to work. It's that obviously, we have millions in the expansion population who want work (and are working) but who would take a brutal economic hit if they're denied financial assistance with their health coverage costs.

Even more importantly, we need to focus on a much more extensive crisis that's right in front of us: This country still is home to millions more Americans in 19 non-expansion states – people who earn $46 or less each day – who continue to be uninsured because they have been denied financial assistance through the Medicaid expansion. They're already in a world of hurt.

Yes. This nation desperately needs a healthcare "fix" – but it needs one that incorporates compassion and humanity, and not vilification.

* For a household of one (single) 138 percent of the Federal Poverty Level for 2017 was $16,643 in the 48 contiguous states and the District of Columbia. It's slightly higher in Hawaii ($19,127) and Alaska ($20,783).

** EDITOR'S NOTE: When I checked with the Health Affairs authors about actual percentages, I was told that the percentage of the able-bodied who were looking for work was actually 13.23 percent – not 12 percent, as noted in the article.

Steve Anderson is editor and content manager for healthinsurance.org, where he's been writing about health insurance and health reform since 2008. He's been fortunate to have worked with a talented team of health policy writers.