Home > Health insurance Marketplace > Alaska

Alaska Marketplace health insurance in 2025

Compare ACA plans and check subsidy savings from a third-party insurance agency.

Alaska health insurance Marketplace guide

If you need help understanding the Alaska Marketplace and choosing the right health insurance plan for you and your family, this guide, including the FAQs below, is for you. For many, an Affordable Care Act (ACA) Marketplace plan may be a good option.

Alaska uses the federally-facilitated HealthCare.gov Marketplace platform, where plans are available from two private health insurance companies — Moda and Premera. If you enroll through the Marketplace, you may qualify for financial help from the government through an advance premium tax credit (most Alaska Marketplace enrollees qualify for these subsidies).

Alaska was among the first states to implement a reinsurance program, which took effect in 2018. This has helped to keep unsubsidized premiums in the state’s individual/family market significantly lower than they would otherwise have been,3

Since 2004, Alaska required fully-insured health plans (i.e. plans that aren’t self-insured) to cover out-of-network care under the state’s 80th percentile rule. But Alaska’s Division of Insurance repealed the 80th Percentile Rule as of January 2024, in a move that generated controversy and a lawsuit filed by medical providers.4 In calling for repeal of the 80th Percentile Rule, Alaska’s insurance regulators expressed concerns that it may have driven healthcare prices higher than they would otherwise be, and noted that it might not be needed anymore, due to the federal No Surprises Act.5

Frequently asked questions about health insurance in Alaska

Who can buy Marketplace health insurance?

Here are the eligibility requirements for health coverage through the Marketplace in Alaska:6

- You must live in Alaska.

- You must be lawfully present in the U.S.

- You must not be incarcerated.

- You must not be enrolled in Medicare.

Although most Alaska residents are thus eligible to use the Marketplace, eligibility for financial assistance (premium subsidies and cost-sharing reductions) has stricter rules. It depends on your income and how it compares with the cost of the second-lowest-cost Silver plan in your area – which depends on your age and location. In addition, to qualify for Marketplace financial assistance you must:

- Not have access to affordable health coverage offered by an employer. If your employer offers coverage but you feel it’s too expensive, you can use our Employer Health Plan Affordability Calculator to see if you might qualify for premium subsidies in the Marketplace.

- Not be eligible for Medicaid or CHIP.

- Not be eligible for premium-free Medicare Part A.7

- If you’re married, you must file a joint tax return with your spouse.8 (with very limited exceptions)9

- Not be able to be claimed by someone else as a tax dependent.10

When can I enroll in an ACA-compliant plan in Alaska?

The open enrollment window in Alaska runs from November 1 to January 15. This is when you can sign up for ACA-compliant individual and family health plans.

For your coverage to start on January 1, you must sign up by December 15. If you enroll between December 16 and January 15, your coverage will begin on February 1.11

You can still make plan changes or enroll in the Marketplace beyond the open enrollment window. However, you must qualify for a special enrollment period (SEP). SEPs generally require a qualifying life event, such as losing your health coverage involuntarily or gaining a dependent.

If you miss the open enrollment deadline and don’t have a qualifying life event, you may still be able to apply if you meet one of the following criteria:

- Your income is below 150% of the poverty level, and you qualify for premium tax credits. In this case, you can enroll anytime.

- You’re a Native American or Alaska Native.12

- You lose Medicaid or CHIP coverage between March 31, 2023 and July 31, 2024. In this case, you can enroll through an extended special enrollment period.13

How do I enroll in a Marketplace plan in Alaska?

To enroll in an Alaska Marketplace health plan, you can:

- Go to HealthCare.gov online – the ACA exchange website.

- Dial the Marketplace Call Center at (800) 318-2596.

- Contact an agent/broker, navigator, or certified application counselor.

- Enroll via an approved enhanced direct enrollment entity.14

Go to localhelp.HealthCare.gov to find a navigator, certified application counselor, or agent in your area.

How can I find affordable health insurance in Alaska?

You can find affordable health insurance in Alaska by shopping on the ACA Marketplace/exchange (HealthCare.gov).

Depending on your income and circumstances, you may qualify for income-based subsidies called Advance Premium Tax Credits (APTC) under the ACA. These credits will reduce the amount you have to pay in premiums each month.

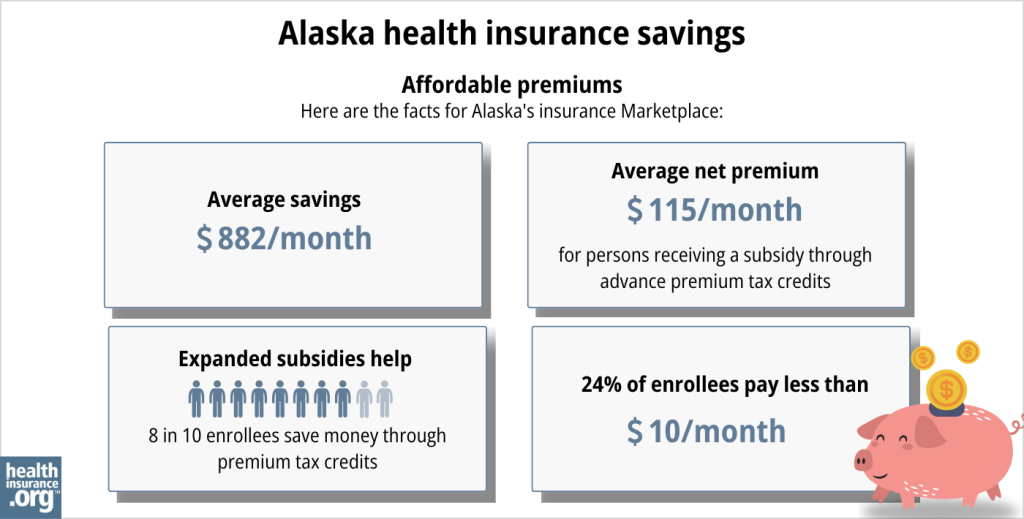

As of early 2024, 87% of Alaska Marketplace enrollees were receiving premium subsidies. The average subsidy amount was $732/month, reducing the average enrollee’s net premium to $215/month.15

(Note that the numbers above are based on effectuated enrollment in early 2024, which is different from the numbers and metrics reported at the end of open enrollment and reflected in the graphic below.)

Source: CMS.gov16

Another way to save money while using the Alaska exchange is cost-sharing reductions (CSR).17 You can qualify for CSR if your income is no more than 250% of the federal poverty level and you enroll in a Silver-level plan.18

Alaska Natives and American Indians qualify for a special version of CSR — with no out-of-pocket costs — if their household income isn’t more than 300% of the federal poverty level. Unlike regular CSR, which is only available on Silver-level plans, the CSR for Alaska Natives and American Indians is available on any metal-level plan.

If you’re not eligible for Marketplace subsidies, other ways to obtain affordable coverage include:

- Apply for Medicaid if you’re eligible: You can begin the enrollment process through HealthCare.gov (you’ll be directed to the state Medicaid program if it appears you’re eligible) or my.alaska.gov. Our Alaska Medicaid eligibility guide walks you through the details of Medicaid eligibility in Alaska.

- Look into short-term health insurance: If you’re looking for a more budget-friendly option, at least one insurer in Alaska offers short-term health insurance plans. However, these plans are not regulated by the ACA and subsidies are not available to offset their cost. If you’re eligible for financial assistance in the Marketplace, a Marketplace plan is likely to be a better option. And starting in September 2024, new short-term health plans will be subject to strict federal duration limits.

How many insurers offer Marketplace coverage in Alaska?

Are Marketplace health insurance premiums increasing in Alaska?

The following average rate changes were approved for Alaska’s Marketplace insurers for 2025, calculated before premium subsidies are applied:

Alaska’s ACA Marketplace Plan 2025 APPROVED Rate Increases by Insurance Company |

|

|---|---|

| Issuer | Percent Increase |

| Moda Assurance Company | 19.85% |

| Premera Blue Cross Blue Shield of Alaska | 13.64% |

Source: RateReview.HealthCare.gov21

When looking at overall average rate changes, it’s important to understand:

- The averages only apply to full-price premiums. Few people pay full price since 87% of Alaska’s exchange enrollees receive subsidies.22 Their net rate change depends on their plan rate and subsidy amount changes.

- Averages don’t account for premiums increasing with age. Even if an insurer doesn’t change rates, you’ll likely pay more each year as you get older. Subsidies may offset this rate change for eligible enrollees.

For perspective, here’s a look at how average pre-subsidy premiums have changed in Alaska’s individual/family market over the years:

- 2015: Average increase of 31% (largest in the nation)23

- 2016: Average increase of 39%24

- 2017: Average increase of 7.3% (and Moda exited the market)25

- 2018: Average decrease of 22%26 (reinsurance program took effect)

- 2019: Average decrease of 3.9%27

- 2020: Average rates unchanged28 (Moda rejoined the market).

- 2021: Average unweighted decrease of 2%29

- 2022: Average decrease of 3.7%30

- 2023: Average increase of 19.1%31

- 2024: Average increase of 16.4%32

How many people are insured through Alaska’s Marketplace?

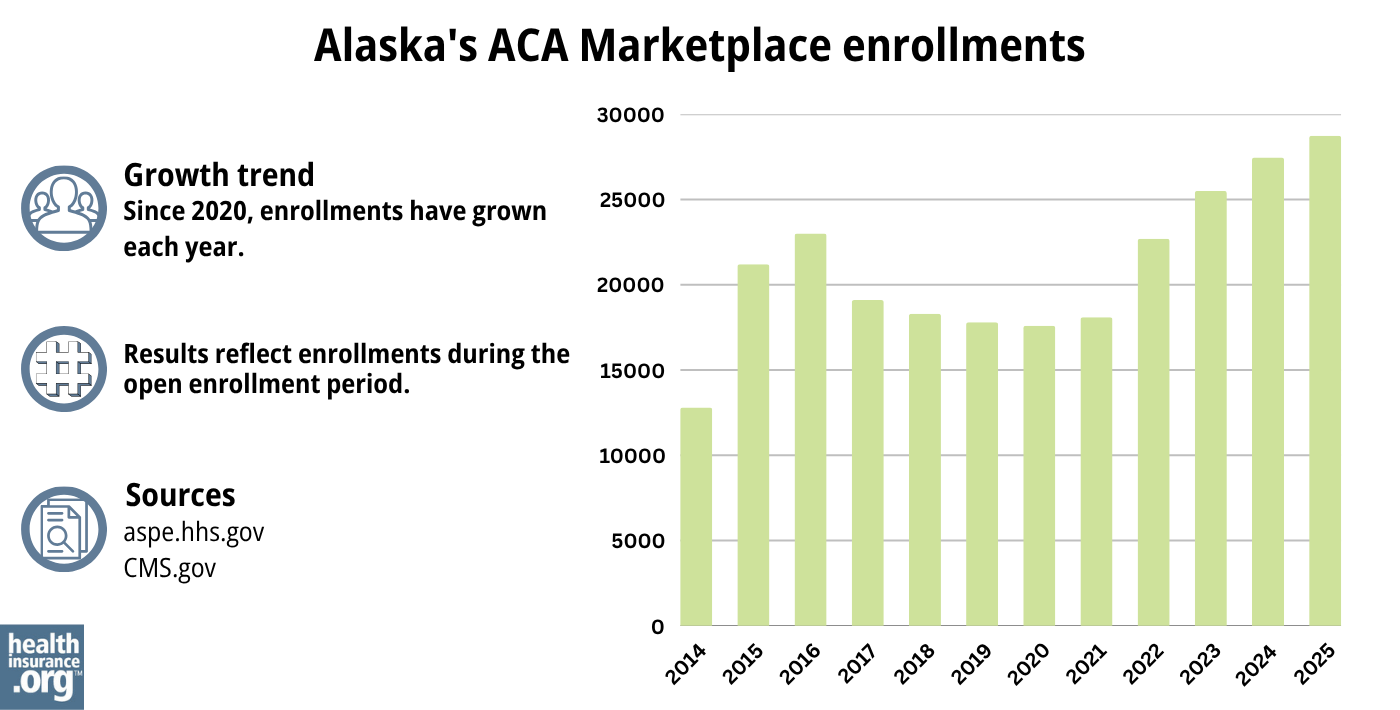

During open enrollment for 2024 health coverage, 27,464 people signed up for private health plans through Alaska’s exchange.33 This was a record high; you can see previous year enrollments in the chart below.

Alaska’s Marketplace enrollment initially peaked in 2016, then declined each year until 2020. But it has been steadily increasing since 2021. This growth is due in part to American Rescue Plan subsidies, which continue through 2025 thanks to the Inflation Reduction Act.34

The enrollment growth in 2024 is also partly due to the “unwinding” of the pandemic-era Medicaid continuous coverage rule. By April 2024, more than 6,000 Alaska residents had transitioned from Medicaid to a Marketplace plan during the unwinding period.35

Source: 2014,36 2015, 37 2016,38 2017,39 2018,40 2019,41 2020,42 2021,43 2022,44 2023,45 2024,46 202547

What health insurance resources are available to Alaska residents?

HealthCare.gov

The official federal website where you can sign up for health insurance plans through the ACA Marketplace.

Denali KidCare

Alaska’s children’s health insurance program.

United Way of Anchorage

Federally funded Navigator organization to assist with Medicaid and exchange enrollment in Alaska.

Alaska State Health Insurance Counseling and Assistance Programs (SHIP)

Enrollment counseling and advice to Medicare beneficiaries and their caregivers.

Medicare Rights Center

A national service for Medicare-related questions.

Alaska Comprehensive Health Insurance Association

Created by the Alaska State Legislature to provide coverage for residents unable to obtain individual health insurance.

Louise Norris is an individual health insurance broker who has been writing about health insurance and health reform since 2006. She has written dozens of opinions and educational pieces about the Affordable Care Act for healthinsurance.org.

Looking for more information about other options in your state?

Need help navigating health insurance options in Alaska?

Explore more resources for options in Alaska including short-term health insurance, dental insurance, Medicaid and Medicare.

Speak to a sales agent at a licensed insurance agency.

Footnotes

- ”2025 OEP State-Level Public Use File (ZIP)” Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Accessed May 13, 2025 ⤶ ⤶

- ”Rate Review Submissions” RateReview.HealthCare.gov. Accessed Jan. 7, 2025 ⤶

- Section 1332 State Innovation Waiver extension request. State of Alaska. March 2022,./efn_note] and the program has been extended through 2027.[efn_note]Alaska: State Innovation Waiver – Extension. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. July 12, 2022. ⤶

- ”Despite opposition from health care providers, Dunleavy administration repeals longstanding regulation meant to hold down costs” Alaska Public Media. January 11, 2024. ⤶

- 80th Percentile Rule. Alaska Division of Insurance. Accessed November 2023. ⤶

- “A quick guide to the Health Insurance Marketplace®” HealthCare.gov, Accessed August, 2023 ⤶

- Medicare and the Marketplace, Master FAQ. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Accessed November 2023. ⤶

- Premium Tax Credit — The Basics. Internal Revenue Service. Accessed MONTH. ⤶

- Updates to frequently asked questions about the Premium Tax Credit. Internal Revenue Service. February 2024. ⤶

- Premium Tax Credit — The Basics. Internal Revenue Service. Accessed January 12, 2024. ⤶

- “A quick guide to the Health Insurance Marketplace®” HealthCare.gov, Accessed August 8, 2023 ⤶

- “AIAN ACA 2021” CMS.gov, Accessed September 18, 2023 ⤶

- “temp-sep-unwinding-faq.pdf” CMS.gov, Jan. 27, 2023 ⤶

- “Entities Approved to Use Enhanced Direct Enrollment” CMS.gov, April 28, 2023 ⤶

- ”Effectuated Enrollment: Early 2024 Snapshot and Full Year 2023 Average” CMS.gov, July 2, 2024 ⤶

- “2025 Marketplace Open Enrollment Period Public Use Files” CMS.gov, May 2025 ⤶

- ”APTC and CSR Basics” Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. June 2023. ⤶

- “Federal Poverty Level (FPL)” HealthCare.gov, 2023 ⤶

- ”Plan Year 2025 Qualified Health Plan Choice and Premiums in HealthCare.gov Marketplaces” Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. October 25, 2024. ⤶

- County by County Plan Year 2025 Insurer Participation in Health Insurance Exchanges. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Accessed Nov. 20, 2024. ⤶

- ”Alaska Rate Review Submissions” RateReview.HealthCare.gov. Accessed Nov. 20, 2024 ⤶

- ”Effectuated Enrollment: Early 2024 Snapshot and Full Year 2023 Average” CMS.gov, July 2, 2024 ⤶

- Analysis Finds No Nationwide Increase in Health Insurance Marketplace Premiums. The Commonwealth Fund. December 2014. ⤶

- Alaska: OUCH. Approved 2016 Individual Market Rate Hikes: 39% Weighted Avg. ACA Signups. August 2015. ⤶

- Premera’s Alaska rates to rise 7 percent next year, less than estimated. Anchorage Daily News. September 2016. ⤶

- 2018 Rate Hikes. ACA Signups. October 2017. ⤶

- 2019 Rate Hikes. ACA Signups. October 2018. ⤶

- 2020 Rate Changes. ACA Signups. October 2019. ⤶

- Alaska: Preliminary Avg. 2021 #ACA Premium Rate Change: -2% Indy Market, -1.9% Sm. Group (Unweighted). ACA Signups. October 2020. ⤶

- *APPROVED* Avg. 2022 #ACA Rate Changeapalooza! AK, CA, GA, HI, IL, KS, LA, MA, MS, MO, NE, NH, TX, WY. ACA Signups. November 2021. ⤶

- Alaska: Final Avg. Unsubsidized 2023 #ACA Rate Changes: +19.1%. ACA Signups. November 2022. ⤶

- Alaska: *Final* Avg. Unsubsidized 2024 #ACA Rate Changes: +16.4% (Updated). ACA Signups. November 2023. ⤶

- ”Marketplace 2024 Open Enrollment Period Report: Final National Snapshot” Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. January 24, 2024. ⤶

- “Health Insurance Marketplaces 2023 Open Enrollment Report” CMS.gov, Accessed August 2023 ⤶

- ”HealthCare.gov Marketplace Medicaid Unwinding Report” Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Data through April 2024; Accessed Aug. 5, 2024 ⤶

- “ASPE Issue Brief (2014)” ASPE, 2015 ⤶

- “Health Insurance Marketplaces 2015 Open Enrollment Period: March Enrollment Report”, HHS.gov, 2015 ⤶

- “HEALTH INSURANCE MARKETPLACES 2016 OPEN ENROLLMENT PERIOD: FINAL ENROLLMENT REPORT” HHS.gov, 2016 ⤶

- “2017 Marketplace Open Enrollment Period Public Use Files” CMS.gov, 2017 ⤶

- “2018 Marketplace Open Enrollment Period Public Use Files” CMS.gov, 2018 ⤶

- “2019 Marketplace Open Enrollment Period Public Use Files” CMS.gov, 2019 ⤶

- “2020 Marketplace Open Enrollment Period Public Use Files” CMS.gov, 2020 ⤶

- “2021 Marketplace Open Enrollment Period Public Use Files” CMS.gov, 2021 ⤶

- “2022 Marketplace Open Enrollment Period Public Use Files” CMS.gov, 2022 ⤶

- “Health Insurance Marketplaces 2023 Open Enrollment Report” CMS.gov, 2023 ⤶

- ”HEALTH INSURANCE MARKETPLACES 2024 OPEN ENROLLMENT REPORT” CMS.gov, 2024 ⤶

- “2025 Marketplace Open Enrollment Period Public Use Files” CMS.gov, May 2025 ⤶