Home > Health insurance Marketplace > Colorado

Colorado Marketplace health insurance in 2025

Compare ACA plans and check subsidy savings from a third-party insurance agency.

Colorado health insurance Marketplace guide

This guide, including the FAQs below, is designed to help you understand your Colorado health insurance options and possible financial assistance available to you and your family — including federal subsidies and Colorado’s state-funded subsidies.

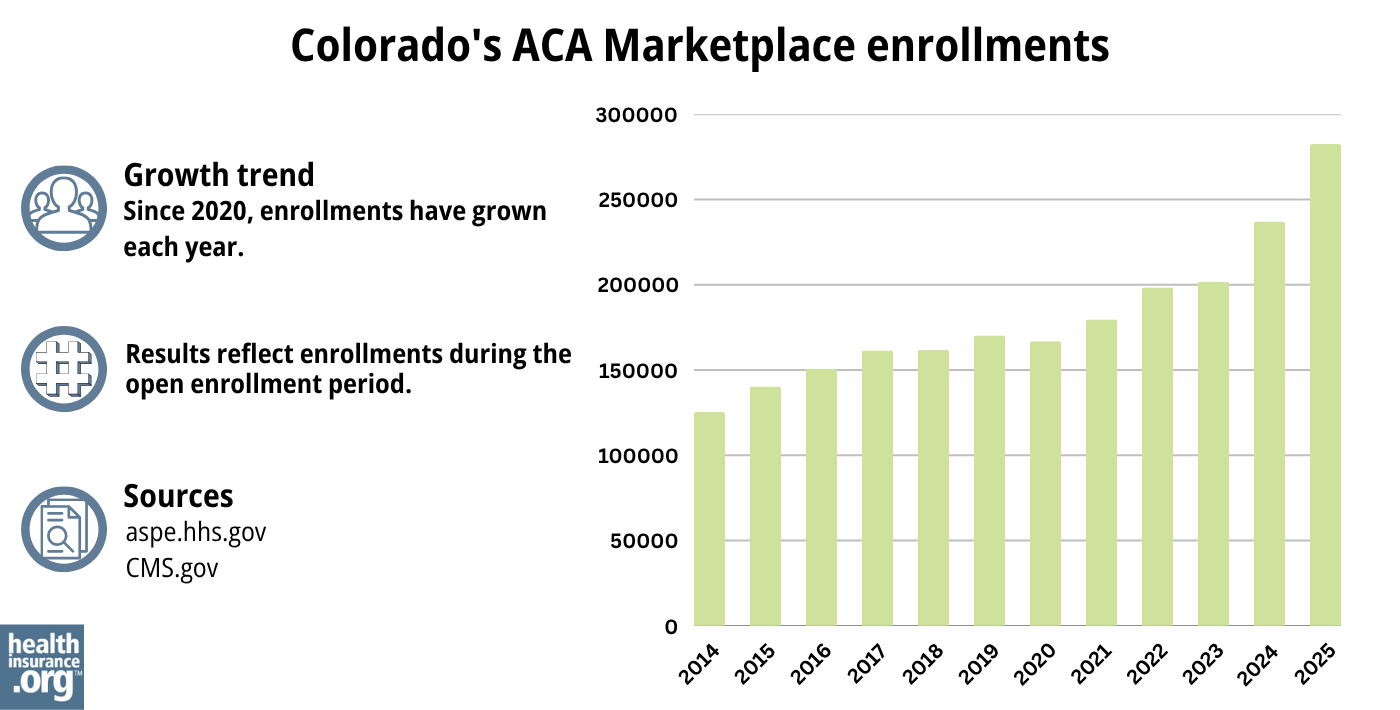

Colorado created its own state-based health insurance exchange (Marketplace), called Connect for Health Colorado. This platform allows residents to shop for individual and family health plans offered by six private health insurance carriers3 (plan availability varies by area). More than 282,000 people enrolled in private plans through Connect for Health Colorado during the open enrollment period for 2025 coverage, which was a significant new record high.4

Connect for Health Colorado also offers dental coverage from four dental insurers, and more than 80,000 people enrolled in these dental plans during the open enrollment period for 2025 coverage.5

The Colorado Option debuted in 2023, bringing standardized plans and lower-cost coverage options to the state’s market. During the open enrollment period for 2025 coverage, nearly half of Colorado Marketplace enrollees selected Colorado Option plans.4

Colorado is also among the states where state-funded subsidies are available, in addition to federal health insurance subsidies (as described below, Colorado’s state-funded subsidies were scaled back a bit starting in 2025, after being temporarily expanded in 2024).

Undocumented immigrants can access these subsidies in Colorado by enrolling in OmniSalud via the Colorado Connect platform, although the number of spots available in this program is limited.6 (As described below, the enrollment process in the subsidy program for undocumented immigrants was different for 2025 coverage, to help ensure continuity of coverage for people already enrolled in the program. Almost 14,000 people enrolled via Colorado Connect for 2025, mostly in the OmniSalud program.4)

Colorado has a reinsurance program that keeps full-price premiums lower than they would otherwise be,7 and also has an easy enrollment program that allows people to access health coverage via the state tax return.8

Frequently asked questions about health insurance in Colorado

Who can buy Marketplace health insurance in Colorado?

To sign up for private health insurance through Connect for Health Colorado, you must:9

- Be a resident of Colorado

- Not be incarcerated

- Not be enrolled in Medicare

- Be lawfully present in the United States. (Colorado has created a separate platform that undocumented residents can use to enroll in state-subsidized health coverage.)10

So most Colorado residents are eligible to enroll in coverage through the exchange. But a bigger question for most people is financial assistance, and a few additional parameters must be met to qualify for subsidies through Connect for Health Colorado.

To qualify for income-based Advance Premium Tax Credits (APTC), federal cost-sharing reductions (CSR), or Colorado’s state-funded cost-sharing subsidies,11 you must:

- Not have access to affordable employer-sponsored health coverage. If you have access to an employer’s plan and aren’t sure whether it’s considered affordable, you can use our Employer Health Plan Affordability Calculator to see if you might qualify for premium subsidies via Connect for Health Colorado.

- Not be eligible for Health First Colorado (Colorado Medicaid) or Child Health Plan Plus (CHP+), or premium-free Medicare Part A.12

- File a joint tax return if you’re married.13

- Not be able to be claimed by someone else as a tax dependent.13

Beyond those basic parameters, qualifying for subsidies through Connect for Health Colorado depends on how much your household earns and how that compares with the cost of the second-lowest-cost Silver plan in your area – which will depend on your age and location.

When can I enroll in an ACA-compliant plan in Colorado?

The federal government has proposed a rule change that would set a nationwide open enrollment schedule of November 1 through December 15, starting in the fall of 2025. If finalized as proposed, this would apply to states like Colorado, that run their own Marketplace.

But for the time being, here’s how open enrollment works in Colorado:

Colorado’s open enrollment period begins November 1 and continues through January 15, allowing Colorado residents to select a health plan for the coming year. This enrollment window is applicable for plans obtained through the exchange, OmniSalud, and directly from insurers (No subsidies are available for plans obtained directly from insurers.)

For coverage to take effect on January 1, your application needs to be completed by December 15. If you enroll between December 16 and January 15, your new coverage will take effect on February 1.14

For OmniSalud (Colorado’s health coverage program for undocumented immigrants), the enrollment process was different for 2025. Instead of a first-come-first-serve approach, OmniSalud coverage renewal was open to existing enrollees from Nov. 1 to Nov. 22, 2024.15 After that, new applicants could enroll, with financial assistance if any remaining spots were left (in the fall of 2023, all of the available financial assistance had been claimed within the first two days of open enrollment beginning16).

Enrollment in OmniSalud ended January 15, 2025, just like all other individual market plans in Colorado. During the open enrollment period for 2025 coverage, nearly 14,000 people enrolled in OmniSalud plans.4

Outside of the annual open enrollment period, you may be eligible to enroll or make a plan change if you experience a qualifying life event, such as giving birth or losing other health coverage.

As of 2024, Colorado joined several other states that consider pregnancy to be a qualifying event.17 This allows uninsured pregnant women the opportunity to enroll in health coverage without having to wait until the baby is born.

Some people can enroll year-round even without a specific qualifying life event.

Enrollment in Health First Colorado (Medicaid) and Child Health Plan Plus (CHP+) is available year-round.18

How do I enroll in a Colorado Marketplace plan?

To enroll in an ACA Marketplace/exchange plan in Colorado, you can:

- Visit Connect for Health Colorado, which is Colorado’s health insurance Marketplace. This online platform will allow you to compare available health plans, determine whether you’re eligible for financial assistance, and enroll in coverage, either during open enrollment or during a special enrollment period.

- Enroll in a Connect for Health Colorado plan with the help of an insurance broker or certified enrollment assister.19

You can reach Connect for Health Colorado’s call center at 855-752-6749 (TTY line: 855-346-3432)

How can I find affordable health insurance in Colorado?

Premium subsidies

Under the Affordable Care Act (ACA), income-based subsidies (APTC) are available to lower the amount you pay for your health coverage each month. These subsidies are available to enrollees who meet the eligibility requirements and select a health plan through Connect for Health Colorado.

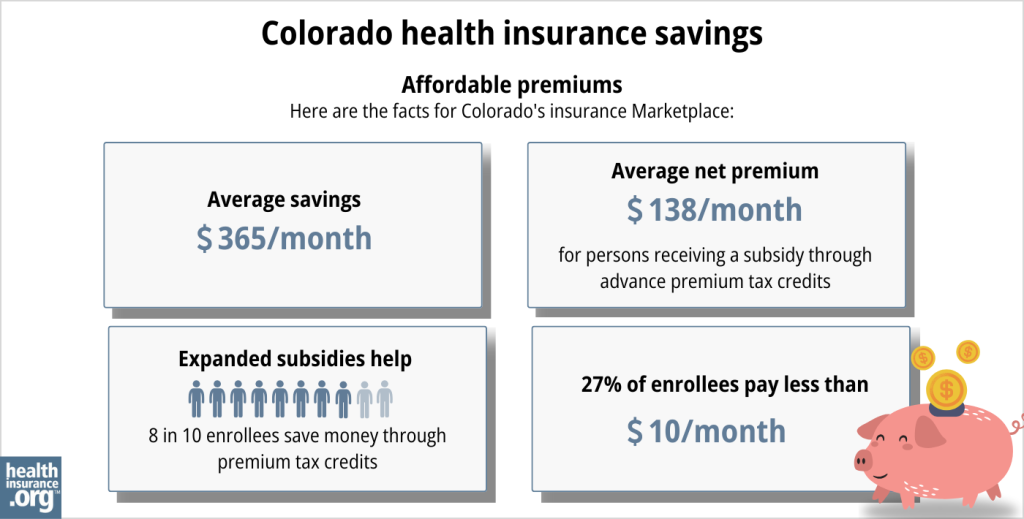

Eighty percent of Connect for Health Colorado enrollees were receiving APTC as of early 2025. For these consumers, the average after-subsidy premium was about $138/month.5

Cost-sharing reductions

If your household’s income doesn’t exceed 250% of the federal poverty level, you’ll also be eligible for federal cost-sharing reductions (CSR), which will reduce your deductible and other out-of-pocket expenses as long as you select a Silver-level plan through the exchange. In 2025, more than 29% of Connect for Health Colorado enrollees were receiving CSR benefits.5

Colorado also offers additional cost-sharing subsidies to silver-plan enrollees with household income up to 200% of the federal poverty level (this benefit had extended to 250% FPL in 2024,20 but the limit was reduced to 200% FPL for 202521).

Colorado’s supplemental cost-sharing subsidies add to federal cost-sharing reductions, resulting in much lower deductibles and other out-of-pocket costs for eligible enrollees.22

If you’re eligible for both APTC and CSR, you can use them both if you enroll in a Silver-level plan through Connect for Health Colorado. (APTC can be used with any metal-level plan, but CSR benefits, including Colorado’s additional state-funded cost-sharing subsidies, are only available if you enroll in a Silver plan.)

Colorado Option (public option) plans provide value

Many Connect for Health Colorado enrollees find that Colorado Option plans present the best overall value. These public option plans accounted for 47% of the state’s Marketplace enrollments in 2025.4 They come with lower premiums than many other plans, as well as lower out-of-pocket costs for various services.23

Health First Colorado (Medicaid) or CHP+

Depending on your income and circumstances, you may be able to enroll in free or low-cost health coverage through Health First Colorado (Medicaid) or CHP+. Learn more about whether you might be eligible for these programs in Colorado.

OmniSalud: Health insurance access for undocumented immigrants

As of 2023, Colorado provides state-funded premium and cost-sharing assistance to undocumented immigrants who enroll through a new public benefit corporation (Colorado Connect/OmniSalud) that the state has created.24 This is separate from Colorado’s health insurance exchange, as undocumented immigrants are not eligible to use an ACA-created health insurance exchange.

In 2023, OmniSalud provided coverage to 10,000 enrollees, and the state announced that the program would be available to 11,000 people for 2024.25

But that 11,000 cap was reached in just the first two days of open enrollment for 2024 coverage.6 After the cap was reached, additional OmniSalud enrollments for 2024 were at full price.

There was no automatic re-enrollment, so people with coverage through OmniSalud in 2023 had to re-enroll during the open enrollment period for 2024 coverage. For 2025, however, Colorado officials said that people with existing OmniSalud coverage would have their spaces saved for 2025, giving them time to renew their coverage before new applicants were given access (if available) to the program.26

For 2025, Colorado officials announced that nearly 14,000 people enrolled in plans via Colorado Connect (the separate platform that Colorado established to facilitate OmniSalud enrollment), most of whom were OmniSalud enrollees.4

Source: CMS.gov 27

A note about Marketplace health benefits: Colorado updated its Essential Health Benefits Benchmark health plan as of 2023 (benchmark plans dictate what must be covered under essential health benefit rules on individual and small group health plans).

Colorado’s changes to the benchmark plan for 2023 include additional mental health coverage, expanded access to drugs that can be prescribed as alternatives to opioids, and up to six acupuncture treatments per year. In addition, Colorado is the first state to explicitly include gender-affirming care in its benchmark plan.28

But this could change in 2026 and future years, due to a proposed federal rule that would prohibit gender-affirming care from being covered as an essential health benefit.

How many insurers offer Marketplace coverage in Colorado?

Six insurers offer 2025 coverage in Colorado’s health insurance Marketplace, with coverage areas that vary by insurer.29

They are the same six insurers that offered coverage for 2024.30 For 2024, SelectHealth joined the health insurance exchange in Colorado, with plans available mostly along the Front Range.31 SelectHealth already offered plans in the exchange in Utah, Idaho, and Nevada. Their expansion into Colorado was due to a merger between Intermountain Health (SelectHealth is Intermountain’s insurance arm) and Colorado-based UCHealth.32

Friday Health Plans offered coverage in early 2023, but stopped accepting new enrollees in May and all FHP policies in Colorado terminated on August 31, 2023.33

Are Marketplace health insurance premiums increasing in Colorado?

For 2025, the following average rate changes were approved for Colorado’s individual/family insurance carriers, according to data published on SERFF34 and by the Colorado Division of Insurance:29

Colorado’s ACA Marketplace APPROVED 2025 Rate Increases by Insurance Company |

|

|---|---|

| Issuer | Percent Increase |

| Cigna Health and Life Insurance | 7.1% |

| Denver Health Medical Plan, Inc | 15.79% |

| SelectHealth | 7.6% |

| Kaiser Foundation Health Plan of Colo. | 7.27% |

| Anthem (HMO Colorado) | 0.15% |

| Rocky Mountain HMO | 8.6% |

Overall the average approved premium increase was 5.6% for 2025.29 This was slightly higher than the average increase of 5.53% that the state’s insurers had initially proposed for 2025.35 Most of the carriers’ approved rates were the same as or very similar to the rates they initially proposed, but the approved average rate increase for Anthem/HMO Colorado was lower than proposed (0.15%36 versus 1.1%35), while the approved average increase for Denver Health Medical Plan was significantly higher than proposed (15.79%36 versus 8.6%35).

It’s important to keep in mind that average rate changes apply to full-price rates, and most enrollees do not pay full price: 78% of the people enrolled through Connect for Health Colorado were receiving premium subsidies in 2024, offsetting some or all of their monthly premium cost.37

Subsidy amounts differ for each enrollee and change annually depending on the cost of the second-lowest-cost Silver plan relative to the enrollee’s household income. As a result of the American Rescue Plan and the Inflation Reduction Act, subsidies are larger than they used to be, and also more widely available; that will continue to be true at least through 2025.38

If the cost of your plan is going up for the coming year, you may want to consider some of the other plans that are available through Connect for Health Colorado. You may find alternatives that offer similar benefits with a lower monthly cost.

Here’s a summary of how Colorado health insurance plans’ average full-price premiums have changed over the years in the individual/family market:

- 2015: Average increase of 0.71%39

- 2016: Average increase of 9.84%40

- 2017: Average increase of 20.4%41

- 2018: Average increase of 34.3%42 (including loss of federal CSR funding)

- 2019: Average increase of 5.6%43

- 2020: Average decrease of 20%44 (reinsurance program took effect)

- 2021: Average decrease of 1.4%45

- 2022: Average increase of 1.1%46

- 2023: Average increase of 10.4%47

- 2024: Average increase of 9.7%48

How many people are insured through Colorado’s Marketplace?

282,481 people enrolled in private plans through Connect for Health Colorado during the open enrollment period for 2025 coverage.5

This was a significant record high, dwarfing the previous record high set the year before, when more than 237,000 people enrolled for 2024.49

The increase in enrollment in recent years is due to the enhancements of federal subsidies under the American Rescue Plan and Inflation Reduction Act, as well as Colorado’s investment in additional state-funded subsidies (see below for a chart detailing enrollment in prior years).

In addition, enrollment growth in 2024 was partly due to the “unwinding” of the pandemic-era continuous coverage rule for Medicaid. People were not disenrolled from Medicaid for three years, but disenrollments resumed in mid-2023. CMS reported that 20,815 Colorado residents transitioned from Medicaid to a Connect for Health Colorado plan during the unwinding process50

Source: 2014,51 2015,52 2016,53 2017,54 2018,55 2019,56 2020,57 2021,58 2022,59 2023,38 2024,60 202561

What health insurance resources are available to Colorado residents?

Connect for Health Colorado: This is the Marketplace/exchange in Colorado. Residents can use Connect for Health Colorado to enroll in individual/family health plans and receive income-based subsidies, and also to enroll in Health First Colorado. You can contact Connect for Health Colorado at 855-752-6749

OmniSalud/Colorado Connect: This state-based platform allows undocumented immigrants to sign up for health coverage. Depending on an applicant’s income and the number of people who have already enrolled, state-funded premium and cost-sharing subsidies may be available.

Colorado Division of Insurance: Regulates the insurance industry in Colorado, and assists consumers and businesses with insurance-related questions and concerns.

Colorado Department of Health Policy and Financing (HCPF): Administers Medicaid (Health First Colorado), Child Health Plan Plus (CHP+) and other health care programs.

Colorado Senior Health Care and Medicare Assistance: A service for Colorado Medicare beneficiaries and their caregivers, providing information and assistance with questions related to Medicare eligibility, enrollment, and claims.

Louise Norris is an individual health insurance broker who has been writing about health insurance and health reform since 2006. She has written dozens of opinions and educational pieces about the Affordable Care Act for healthinsurance.org.

Looking for more information about other options in your state?

Need help navigating health insurance options in Colorado?

Explore more resources for options in Colorado including short-term health insurance, dental insurance, Medicaid and Medicare.

Speak to a sales agent at a licensed insurance agency.

Footnotes

- ”2025 OEP State-Level Public Use File (ZIP)” Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Accessed May 13, 2025 ⤶ ⤶

- ”Polis-Primavera Administration’s Landmark Reinsurance Effort Will Save Coloradans $493 Million on Healthcare Premiums in 2025, Putting Money Back in the Pockets of Hardworking Coloradans” Colorado Division of Insurance. Oct. 17, 2024 ⤶

- “Polis Administration’s Landmark Health Insurance Programs Continue to Deliver Millions in Savings for Coloradans” Colorado Division of Insurance, July 20, 2023 ⤶

- ”Connect for Health Colorado Sets a New Record: 282,483 People Enrolled in Health Insurance for Plan Year 2025” Connect for Health Colorado. Jan. 23, 2025 ⤶ ⤶ ⤶ ⤶ ⤶ ⤶

- ”By the Numbers: Open Enrollment Report for Plan Year 2025” Connect for Health Colorado. Apr. 11, 2025 ⤶ ⤶ ⤶ ⤶

- OmniSalud Financial Help Spots Claimed for 2024. Connect for Health Colorado. November 2, 2023. ⤶ ⤶

- ”Polis-Primavera Administration’s Landmark Reinsurance Program to Save Coloradans $477 Million on Premiums in 2025” Colorado Division of Insurance. July 17, 2024 ⤶

- ”Health Care Coverage Easy Enrollment Program” Colorado General Assembly. Enacted 2020. ⤶

- ”Who can sign up?” Connect for Health Colorado, accessed August 2023 ⤶

- “OmniSalud” Connect for Health Colorado, accessed August 2023 ⤶

- ”Evaluation of the Colorado Health Insurance Affordability Enterprise FY 2022/23” Colorado Division of Insurance, June 1, 2023 ⤶

- “Lower Your Monthly Premiums” Connect for Health Colorado, accessed August 2023 ⤶

- Premium Tax Credit — The Basics. Internal Revenue Service. Accessed MONTH. ⤶ ⤶

- “After You Buy” Connect for Health Colorado, accessed August 2023 ⤶

- ”2025 Health Coverage Open Enrollment” Boulder County Human Services. Accessed Oct. 17, 2024 ⤶

- ”OmniSalud Health Insurance for Undocumented Coloradans Enrollment Hits Funding Cap in Just 2 Days; Demonstrates Need For More Investment” Colorado Immigrant Rights Coalition. Nov. 3, 2023 ⤶

- “HB22-1289: Health Benefits for Colorado Children and Pregnant Persons” Colorado General Assembly. Enacted June 7, 2022. ⤶

- “Is there an open enrollment period for Health First Colorado?” Health First Colorado, July 17, 2016 ⤶

- “Need Help with Your Health Coverage? Find Enrollment Assistance and More Using Connect for Health Colorado’s Certified Experts” Connect for Health Colorado, accessed August 2023 ⤶

- “Amended Regulation 4-2-78 Concerning Cost Sharing Reduction Enhancements” Colorado Division of Insurance, accessed August 2023 ⤶

- ”Colorado Health Insurance Affordability Board Meeting Minutes” Colorado Health Insurance Affordability Enterprise. April 19, 2024 ⤶

- “Amended Regulation 4-2-78 Concerning Cost Sharing Reduction Enhancements” Colorado Division of Insurance, accessed August 2023 ⤶

- ”Colorado Option” Colorado Department of Regulatory Agencies. Accessed Jan. 23, 2025 ⤶

- “Colorado Division of Insurance looking for public health AmeriCorps members to join Enroll for Health Colorado” Colorado Division of Insurance, accessed August 2023 ⤶

- ”OmniSalud program will provide $0 premium health plans to 11,000 qualified individuals” Colorado Division of Insurance. October 2023. ⤶

- ”Health Insurance Affordability Board Meeting” (board meeting slides) Colorado Health Insurance Affordability Enterprise. May 17, 2024 ⤶

- “2025 Marketplace Open Enrollment Period Public Use Files” CMS.gov, May 2025 ⤶

- ”Biden Administration Announces Approval of Colorado’s Inclusive Health Care Plan to Set Colorado’s Essential Health Benefits” Colorado Department of Regulatory Agencies. October 12, 2021. ⤶

- “Polis-Primavera Administration’s Landmark Reinsurance Effort Will Save Coloradans $493 Million on Healthcare Premiums in 2025, Putting Money Back in the Pockets of Hardworking Coloradans” Colorado Division of Insurance. Oct. 17, 2024 ⤶ ⤶ ⤶

- “Polis Administration’s Landmark Health Insurance Programs Continue to Deliver Millions in Savings for Coloradans” Colorado Division of Insurance, July 20, 2023 ⤶

- “Two Colorado health care giants are forming one big insurance network. But will consumers actually benefit? ” Colorado Sun, Jan. 24, 2023 ⤶

- “Intermountain Healthcare and SCL Health Complete Merger” SCL Health, April 5, 2022 ⤶

- “Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) for Customers Losing Friday Health Plans Coverage as of August 31, 2023” Colorado Division of Insurance, Aug. 3, 2023 ⤶

- “SERFF Filing Access” SERFF, accessed Oct. 17, 2024 ⤶

- “Preliminary 2025 Health Insurance Information — Individual and Small Group” Colorado Division of Insurance, accessed July 26, 2024 ⤶ ⤶ ⤶

- “Polis-Primavera Administration’s Landmark Reinsurance Effort Will Save Coloradans $493 Million on Healthcare Premiums in 2025, Putting Money Back in the Pockets of Hardworking Coloradans” Colorado Division of Insurance. Oct. 17, 2024 ⤶ ⤶

- ”Effectuated Enrollment: Early 2024 Snapshot and Full Year 2023 Average” CMS.gov, July 2, 2024 ⤶

- “Health Insurance Marketplaces 2023 Open Enrollment Report” CMS.gov, Accessed August 2023 ⤶ ⤶

- ”2015 Health Insurance Plans & Rates – Division of Insurance Rate Review FAQ” Colorado Division of Insurance. September 22, 2014. ⤶

- ”HB16-1336 Sen Donovan (Prime Sponsor), Sen Roberts (Co-Sponsor), “Study Geographic and Cost Drivers of Individual Health Plans”” Coloradokids.org Accessed October 2023. ⤶

- ”Dramatic Price Increases A Look at Colorado’s 2017 Individual and Small Group Insurance Premiums” Colorado Health Institute. September 2016. ⤶

- ”Colorado 2018 Individual Market Final Rate Changes ‐ No CSR Funding” Colorado Division of Insurance. Accessed October 2023. ⤶

- ”Colorado finalizes 2019 health insurance premium rates; some individuals could see rates fall” Denver 7 ABC News. October 2018. ⤶

- ”2020 Colorado Insurance Rates and the Role of Reinsurance” Colorado Health Institute. January 16, 2020. ⤶

- ”2021 individual health premiums decreasing by 1.4% over 2020 premiums” Colorado Division of Insurance. October 8, 2020. ⤶

- ”2022 Individual Consumer Impact” Colorado Division of Insurance. October 2021. ⤶

- ”Division of Insurance Works to Save Coloradans $326 million on Health Insurance in 2023” Colorado Division of Insurance. October 2022. ⤶

- ”2024 Individual Market – Reinsurance Impact By Carrier” Colorado Division of Insurance. October 2023. ⤶

- Colorado’s Health Insurance Marketplace Finishes Open Enrollment with More Than 237,000 Sign-Ups, A New Record. Connect for Health Colorado. January 2024. ⤶

- State-based Marketplace (SBM) Medicaid Unwinding Report. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Accessed Jan. 23, 2025; Data through September 2024 ⤶

- “ASPE Issue Brief (2014)” ASPE, 2015 ⤶

- “Health Insurance Marketplaces 2015 Open Enrollment Period: March Enrollment Report”, HHS.gov, 2015 ⤶

- “HEALTH INSURANCE MARKETPLACES 2016 OPEN ENROLLMENT PERIOD: FINAL ENROLLMENT REPORT” HHS.gov, 2016 ⤶

- “2017 Marketplace Open Enrollment Period Public Use Files” CMS.gov, 2017 ⤶

- “2018 Marketplace Open Enrollment Period Public Use Files” CMS.gov, 2018 ⤶

- “2019 Marketplace Open Enrollment Period Public Use Files” CMS.gov, 2019 ⤶

- “2020 Marketplace Open Enrollment Period Public Use Files” CMS.gov, 2020 ⤶

- “2021 Marketplace Open Enrollment Period Public Use Files” CMS.gov, 2021 ⤶

- “2022 Marketplace Open Enrollment Period Public Use Files” CMS.gov, 2022 ⤶

- ”HEALTH INSURANCE MARKETPLACES 2024 OPEN ENROLLMENT REPORT” CMS.gov, 2024 ⤶

- “2025 Marketplace Open Enrollment Period Public Use Files” CMS.gov, May 2025 ⤶