Will “repeal and replace” implode?

The American Health Care Act (AHCA) is House Republicans’ bill to repeal and replace the Affordable Care Act. The bill is also politically self-immolating. I just don’t understand what Republicans are trying to do here.

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) is the closest we have to a nonpartisan referee who can fairly assess the likely impact of complicated legislation. Although its director was hand-picked by Speaker Ryan and the Republican majority, CBO has admirably retained its professional independence. That’s especially important in this polarized time.

Brutal from political and human perspectives

CBO’s official score of AHCA was released this afternoon. I’ll let my buddy Charles Gaba give the details. Briefly put, CBO’s numbers are brutal from both a political and human perspective. If the AHCA passes as written, by the end of next year, fourteen million fewer Americans will have health insurance. Twenty-four million more people will be uninsured by 2026.

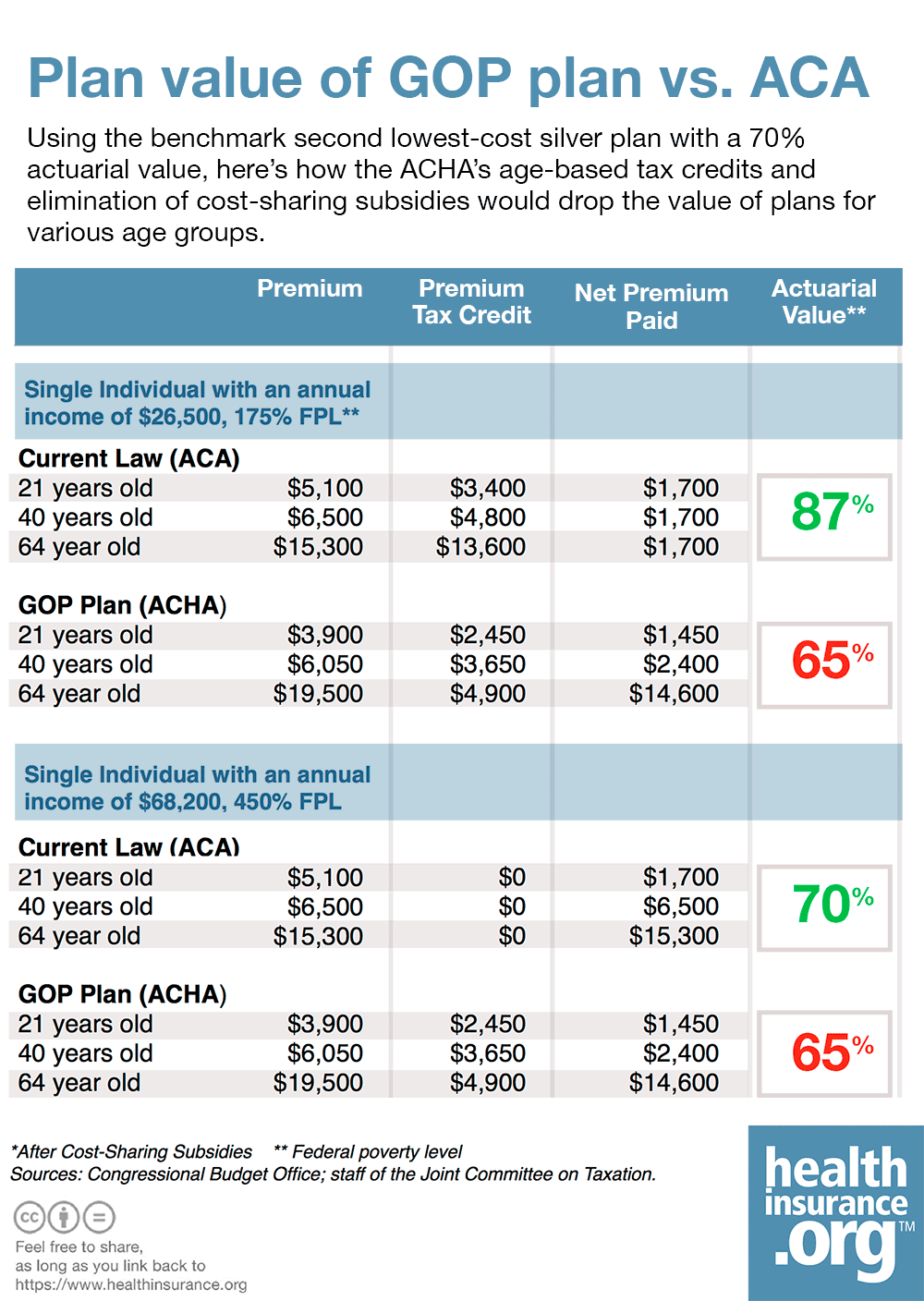

And the bad news keeps coming. Table 4 of CBO’s report describes the impact of AHCA on nongroup health insurance premiums. As I read the table, a 64-year-old with a yearly income of $26,500 would see his annual net premium increase from $1,700 to a whopping $14,600—and this for a markedly less generous plan.

Whatever the policy issues, a $12,900 premium increase on low-income 64-year-olds is political suicide. If this actually happened, Republicans would be destroyed at the polls next November. This was utterly predictable, too, given the main features of the Republican bill.

A shambolic legislative process

Which raises a strange question: How and why did Republicans propose such a politically damaging plan in the first place? I have been studying and practicing health policy for more than twenty years. I have never seen a less-professional, more shambolic legislative process than the one Republicans are now pursuing.

From a political perspective, Obamacare has never been more popular, now that its survival is genuinely in doubt. Virtually every provision of its Republican alternative is disliked. Most Americans, including most Trump supporters, support ACA’s Medicaid expansion as it is. Huge majorities support ACA’s higher taxes on Americans making more than $250,000 to support health care, support ACA’s more generous subsidies to people of modest incomes who have trouble affording coverage.

Democrats are united in opposition to AHCA. That’s unsurprising. As one Republican congressman told me: “The Democrats can’t work with us, not after the way Trump campaigned.” More impressive, Republicans have managed to propose something opposed by nearly every major interest group: the American Hospital Association, the American Medical Association, AARP, and the health insurance industry. Anti-ACA conservative commentators hate the bill. Republican governors in Ohio, Illinois, Massachusetts, Arizona, and Nevada have also come out against key pillars of AHCA, as have key Republican Senators.

From a policy-wonk perspective, Republicans are doing scarcely better. Merely debating AHCA runs the risk of destabilizing the individual insurance market, whose proposed 2018 premiums will be announced beginning in May. Republicans’ proposed alternative to the individual mandate—the one truly unpopular component of Obamacare—does too little to maintain coverage and to stabilize health insurance premiums. Republican politicians, having just been savaged at unruly town halls, dread what may come next if they are held responsible for millions of people losing coverage and nightly news coverage of cancer patients with bills they can’t pay.

Are the Republicans even trying?

So as of now, Republicans have created a political and policy fiasco. Perhaps this fiasco is the result of simple incompetence. But AHCA is such a fiasco that I wonder, alongside many others, whether Republicans are even trying to pass it. Whatever the cause, the driving dynamic behind this fiasco is noteworthy.

Most important, Republicans failed to put in the work at the interface of politics and policy required to responsibly turn our $3.4 trillion medical political economy. Democrats crafted ACA over many months and years. The process involved repeated CBO scoring, analysis inside and outside government by many of America’s most respected health policy experts who knew this was hard, and really wanted to get things right. Democrats did the hard political and policy work in 2006, 2007, and 2008 that presaged the ACA, long before anyone expected Barack Obama to be President, Democratic Party interest groups and policy experts had gotten together, hashed out their differences, and coalesced around what would eventually become ACA. Had the 2008 primaries played out somewhat differently, we would now be debating ClintonCare or EdwardsCare, which would have both looked much like ACA. The Senate bill that became ACA included more than 150 Republican amendments, too.

Not that ACA is perfect—far from it. Working and middle-class people need more financial help than ACA provides. (Had ACA done more there, Hillary Clinton would now be President. Well, that’s another story.) ACA’s so-called “family glitch” excluded many people with poor workplace coverage. Out of partisan spite, deep-red states shut out three million poor people from coverage under the new law. Tim Jost and I, and a crack Urban Institute team, have proposed many ways to improve ACA. Most realistic fixes to ACA require more spending, not less. You can’t slash spending on ACA and provide better insurance coverage.

AHCA is visibly rushed and shoddy

Whatever ACA’s defects, AHCA looks visibly rushed and shoddy by comparison. Republicans just haven’t put in the work. We don’t even know how shoddy AHCA is, since the bill has barely been exposed to careful scrutiny, let alone being road tested on our $3.4 trillion medical economy. In theory, President Trump and his administration could step in to coordinate Republican efforts, to craft and mobilize behind a more substantial bill to address these problems. So far, anyway, the President lacks the expertise, the personal credibility, or consistent focus to play this unifying role. Although he is well-liked among Republican primary voters, he is disliked and distrusted by most Republican political professionals. That’s an obstacle, too.

Republicans have also been dishonest about what Obamacare actually is and what is required to make it better. Since 2010, Republicans such as Rep. Tom Price honed their legislative chops by preparing “repeal and replace” bills that would snatch coverage from twenty million people while damaging state budgets and punishing health care providers.

GOP voters called their bluff

Since these measures would never be enacted, Republicans in Washington paid no political price. Out of power, they could market to their co

re constituents who distrusted Democrats. They could attack Medicaid expansion as another wasteful welfare program that provides bad insurance to unworthy people, and complain about death panels. They could lambast ACA’s marketplaces for high premiums and deductibles that any realistic Republican proposal would actually make worse. They could avoid speaking to voters about the one policy change Republicans actually agreed upon: cutting the taxes on wealthy people used to finance Medicare and ACA.

Once Republicans unexpectedly seized power in Washington, their previous political pitch doesn’t work anymore. They can spend less money on ACA—but only by some combination of covering fewer people, cutting Medicaid, offering smaller exchange subsidies, or offering more skimpy coverage. The American public prefers Obamacare to each of these options.

There is another thing, too. Democrats and Republicans across the country have big political differences. But it turns out that many want ACA to work. Medicaid expansion is the public health jewel of ACA. In Ohio, Indiana, Kentucky, and elsewhere, Republican governors and the Obama administration have admirably negotiated, spending billions of dollars to expand coverage, keep open rural hospitals, address the opioid epidemic in rural America. In my own research, I’ve talked with addiction professionals around the country who work for Republican governors and legislators. Many are proud of what they have accomplished.

Medicaid expansion: surprisingly durable

In part because Republican governors helped to craft and run it, Medicaid expansion seems surprisingly durable. Ironically, it has greater bipartisan support than the market-oriented ACA marketplaces do. The marketplaces are more fragile, often offer a worse human experience than Medicaid does, and have no local political owner aside from the President of the United States. Giving Republican governors a stake turns out to be the secret weapon in sustaining expanded health insurance coverage.

At least that’s how things look right now. I confess I have no idea what will happen on health reform. Republicans have a huge stake in passing something, given that repealing Obamacare was a central campaign promise. ACA died a thousand deaths before it was passed. I’d wage Republicans will find some way to pass something.

What they’re unlikely to do is to uproot ACA in its entirety. Democratic resistance, the sheer inertia of American politics, and their own legislative shoddiness may have precluded that. Perhaps if they are wise, they will cut ACA’s taxes on the wealthy and leave everyone’s insurance alone. Perhaps that is the best bipartisan compromise on health reform.

Harold Pollack is the Helen Ross Professor at the School of Social Service Administration. He is also Co-Director of The University of Chicago Crime Lab. He has published widely at the interface between poverty policy and public health. Pollack serves as a Fellow at the MacLean Center for Clinical Ethics at the University of Chicago, and as an Adjunct Fellow at the Century Foundation.

Get your free quote now through licensed agency partners!