Medicaid eligibility and enrollment in Kentucky

Medicaid enrollment in Kentucky has increased 142% since 2013

Who is eligible for Medicaid in Kentucky?

Kentucky’s Medicaid eligibility levels are as follows (these limits include a built-in 5% income disregard that’s used for income-based Medicaid eligibility determinations):

- Children up to age 1 with family income up to 200% of the federal poverty level (FPL)

- Children ages 1 to 18 with family income up to 64% of FPL

- Children with family income too high to qualify for Medicaid are eligible for the Kentucky Children’s Health Insurance Program (KCHIP); KCHIP is available to kids with family income up to 218% of FPL

- Pregnant women with family income up to 200% of FPL (coverage for the mother continues for 12 months after the baby is born)

- Parents and other adults are covered with incomes up to 138% of FPL

Kentucky Medicaid is also available to individuals who are disabled and those who are 65 or older, but eligibility rules for those populations include both income and asset/resource limits.

Apply for Medicaid in Kentucky

Enroll online at Kynect. Apply by telephone by calling 1-855-459-6328 or TTY 1-855-326-4654. Apply in person at a local office of the Department for Community Based Services.

Eligibility: Children up to age 1 with family income up to 195% of FPL. Children ages 1-18 with family income up to 159% of FPL; children with family income up to 213% of FPL are eligible for the Kentucky Children’s Health Insurance Program. Pregnant women with family income up to 195% of FPL. Adults with income up to 138% of FPL. See the Programs and Services page for guidelines for elderly, disabled, and others who may qualify.

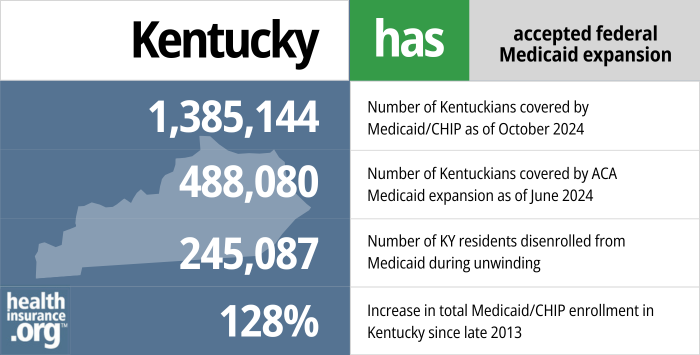

Did Kentucky expand Medicaid under the ACA?

Yes, Kentucky accepted federal funding to expand Medicaid starting in 2014. Kentucky has been one of the most successful states in using Affordable Care Act (ACA) provisions to reduce its uninsured rate — both by expanding Medicaid and adopting a state-run health insurance marketplace. (For a few years, Kentucky transitioned to having a state-run marketplace that used the HealthCare.gov enrollment platform. But Kentucky went back to having a fully state-run exchange platform as of the fall of 2021.)

- 1,385,144 – Number of Kentuckians covered by Medicaid/CHIP as of October 20241

- 488,080 – Number of Kentuckians covered by ACA Medicaid expansion as of June 20242

- 245,087 – Number of KY residents disenrolled from Medicaid during unwinding3

- 128% – Increase in total Medicaid/CHIP enrollment in Kentucky since late 20134

Explore our other comprehensive guides to coverage in Kentucky

This guide was developed to help you understand the health coverage options available to you and your family in Kentucky. The options found in Kentucky’s ACA Marketplace may be a good choice for many consumers, and we will guide you through the options.

Hoping to improve your smile? Dental insurance may be a smart addition to your health coverage. Our guide explores dental coverage options in Kentucky.

Use our guide to learn about Medicare, Medicare Advantage, and Medigap coverage available in Kentucky as well as the state’s Medicare supplement (Medigap) regulations.

Short-term health plans provide temporary health insurance for consumers who may find themselves without comprehensive coverage.

Frequently asked questions about Kentucky Medicaid eligibility and enrollment

How do I apply for Medicaid in Kentucky?

You can do any of the following to apply for Medicaid in Kentucky if you are under 65 (and don’t have Medicare):

- Enroll online using HealthCare.gov or Benefind.ky.gov.

- Apply by telephone (HealthCare.gov) by calling 1-800-318-2596 or TTY 1-855-889-4325, or Benefind at 1-855-306-8959 (these phone numbers are for applicants under age 65)

- Download a paper application. Mail your application to the DCBS Family Support P.O. Box 2104 Frankfort KY 40602. You may also fax your application to 1-502-573-2007.

If you are 65 or older or have Medicare, you can apply for Kentucky’s Medicare Savings Program, which is run by the state Medicaid office.

How does Medicaid provide assistance to Medicare beneficiaries in Kentucky?

Many Medicare beneficiaries also receive help through Medicaid with the expense of Medicare premiums, prescription drugs, and services that aren’t covered by Medicare — like long-term care.

Our guide to financial resources for Medicare enrollees in Kentucky includes overviews of those programs, including Medicare Savings Programs, long-term care benefits, and income guidelines for assistance.

How is Kentucky handling Medicaid renewals after the pandemic?

To address the COVID pandemic, Medicaid disenrollments were paused nationwide from March 2020 through March 2023. People were not disenrolled from Medicaid during that time, even if their circumstances changed and they were no longer eligible for Medicaid. But the federal continuous coverage requirement ended March 31, 2023, and states have a 12-month “unwinding” period when they must initiate eligibility redeterminations for all Medicaid enrollees. People who are no longer eligible, as well as people who fail to respond to a renewal notice, will be disenrolled from Medicaid.

Under the federal rules, disenrollments could come as early as April 1, 2023, but Kentucky has opted to have the first round of disenrollments happen at the end of May (ie, people with a May 31 renewal date who are no longer eligible or who fail to respond to a renewal notification).

The state estimates that more than 236,000 people could potentially lose their Medicaid benefits in Kentucky during the unwinding period. This includes people whose income has increased above the Medicaid-eligible limits, people who were eligible due to pregnancy and are now more than 12 months postpartum, and people who have aged out of Medicaid for children or Medicaid expansion (ie, turned 19 or 65).

Kentucky will prioritize renewals for people who are eligible for Medicare, starting in May and continuing for six months. In June, they will begin processing renewals for people they believe to now be eligible for a qualified health plan (QHP) in the exchange (Kynect) instead of Medicaid, and those renewals will continue throughout the unwinding period. In all cases, the person will have the opportunity to submit additional updated information during their renewal process, and may end up eligible to continue their Medicaid after all.

Kentucky is spreading the renewals out over the full 12 months of the unwinding period, but the heaviest renewal volume will come in the final few months (February to April 2024), so that the state can build on lessons learned earlier in the process. There will be a smaller number of renewals in the early months (May and June 2023) and around the holidays (November and December 2023), to account for the initial learning curve for Medicaid office employees and the holiday schedule and workload increase due to open enrollment at the end of the year.

So although renewal notices will start to go out to enrollees in the spring of 2023, many people will not get a renewal notification from Kentucky Medicaid until early 2024. In general, Kentucky will be processing the longest-pended renewals first, but in households where multiple family members have Medicaid with different renewal dates, they will process the whole family together with the latest renewal date.

People who lose Medicaid will be able to transition to an employer’s plan (if available), Medicare, or to an individual/family plan obtained through Kynect. In all cases, there’s a limited enrollment window, and it’s important to sign up for new coverage before the date that Medicaid ends, in order to avoid a gap in coverage.

How many people are enrolled in Kentucky Medicaid?

Medicaid expansion in Kentucky was effective as of Jan. 1, 2014. In the fall of 2013 — before the first open enrollment period under the Affordable Care Act — 606,805 people were enrolled in Kentucky’s Medicaid/CHIP program. By early 2023, total Medicaid/CHIP enrollment in Kentucky was up 168%, to more than 1.6 million people. That amounted to nearly 37% of all Kentucky residents covered by Medicaid.

Nationwide, Medicaid enrollment was up 62% as of early 2022, Kentucky’s 168% increase at that point was by far the highest in the nation. The growth was driven by Medicaid expansion as well as the COVID pandemic (including the Families First Coronavirus Response Act, which paused Medicaid eligibility redeterminations during the pandemic).

Legislation impacting Kentucky Medicaid

Does Kentucky have a Medicaid work requirement?

No, Kentucky does not currently have a Medicaid work requirement. After more than three years of debate and legal wrangling, Kentucky’s Medicaid work requirement, which never actually took effect, was rescinded in 2019. Governor Andy Beshear took office in December 2019 and one of his first acts was to sign an executive order that rescinded former Governor Bevin’s 2018 executive order that had begun the process of creating a Medicaid work requirement in Kentucky. Beshear’s administration notified CMS that the state was terminating the Kentucky HEALTH waiver, and the state stopped defending the program in the lawsuit that had held up the implementation of the work requirement since mid-2018.

But Kentucky lawmakers are still trying to implement a Medicaid work requirement. Legislation (HB 7) was enacted in 2022 after lawmakers overrode Gov. Beshear’s veto. It called for the state to implement a Medicaid work requirement by April 2023, for non-disabled adults (19 – 59) without dependent children who have been enrolled in Medicaid for more than 12 months. The legislation does note that the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services would have to approve the work requirement. That won’t happen under the Biden administration, but approval could be granted by a future administration.

Kentucky Medicaid’s work requirement history

Kentucky residents elected Matt Bevin in November 2015 (incumbent Steve Beshear — Andy’s father — was term-limited and could not run). Bevin, a Tea Party Republican, had expressed his desire to pull back from the existing Medicaid expansion in Kentucky. Early in 2015, Bevin said he would eliminate Medicaid expansion entirely, but his position softened towards the end of the campaign. By 2016, Bevin no longer planned to eliminate coverage for the nearly half a million people who had obtained Medicaid under Kentucky’s expansion. Instead, he proposed that the state seek a Section 1115 waiver from the federal government to allow Kentucky to design its own version of Medicaid expansion.

In August 2016, Bevin did just that, submitting his Kentucky HEALTH Section 1115 demonstration waiver proposal to HHS for review. Bevin’s administration initially anticipated federal approval by summer 2017, and enactment of the waiver provisions as of January 2018. Ultimately, that time frame was pushed back a bit, with federal approval coming in January 2018, with the bulk of the waiver set to be implemented in July 2018.

The Kentucky HEALTH waiver applied to non-disabled Medicaid enrollees ages 19-64, and most of the provisions in the waiver constituted benefit cuts in an effort to control costs. But Kentucky HEALTH did not apply to disabled Medicaid enrollees, or to those younger than 19 or older than 64.

Kentucky’s waiver included a requirement that enrollees work at least 80 hours per month (or otherwise participate in “community engagement” activities — like job training or community service — for at least 80 hours per month). When Kentucky’s waiver was initially approved in January 2018, it was the first time that CMS approved a work requirement for Medicaid (Arkansas was able to implement their work requirement first, in June 2018, but Kentucky’s was approved first; the work requirement in Arkansas was later blocked by the same judge who blocked Kentucky’s work requirement).

A lawsuit was filed by consumer advocacy groups on behalf of several Kentucky residents who had Medicaid coverage, challenging the legality of the work requirement waiver. On June 29, 2018, just two days before Kentucky’s work requirement was scheduled to take effect, U.S. District Judge James E. Boasberg ruled that HHS should never have approved Kentucky’s waiver, as it conflicts with Medicaid’s mission. Boasberg wrote that the Secretary of HHS “never adequately considered whether Kentucky HEALTH would, in fact, help the state furnish medical assistance to its citizens, a central objective of Medicaid. This signal omission renders his determination arbitrary and capricious. The Court, consequently, will vacate the approval of Kentucky’s project and remand the matter to HHS for further review.”

Once the state’s waiver was blocked, the Bevin Administration indicated that they were considering ending Medicaid expansion in Kentucky in order to address budget shortfalls. But that did not come to pass.

In July 2018, HHS reopened a public comment period for the proposed Kentucky HEALTH waiver, ostensibly seeking public input on the waiver and how to address the court’s decision. They received nearly 8,500 comments expressing opposition to the proposed work requirement, and just 374 comments that were supportive of it. But in November, CMS reapproved the Kentucky HEALTH waiver, with very little in the way of changes. The work requirement was still included, as were monthly premiums and the elimination of retroactive coverage.

The new waiver approval was scheduled to take effect April 1, 2019, but on March 27, 2019, Judge Boasberg once again blocked implementation of Kentucky HEALTH, noting that Kentucky and HHS had not remedied the central flaw in the Kentucky HEALTH waiver: The fact that numerous people were likely to lose coverage if a work requirement was implemented. The state published a series of FAQs following the ruling, clarifying that Kentucky HEALTH was not being implemented on April 1 due to the court decision, and that a rescheduled implementation date had not been set. Kentucky’s Cabinet for Health and Family Services also issued a statement, emphatically disagreeing with Judge Boasberg’s ruling.

The Trump administration and the state of Kentucky appealed Boasberg’s ruling in April 2019, and oral arguments were heard by a three-judge panel on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit in October 2019. All three judges expressed concerns that mirrored Boasberg’s, casting doubt on whether the work requirement would prevail (and as noted above, Kentucky withdrew itself from the lawsuit as of December 2019).

Although Trump administration lawyers debated the semantics of the coverage losses (arguing — without much in the way of evidence — that work requirements will lead to people being covered by employer-sponsored plans or private plans in the individual market instead of Medicaid), it’s important to understand that when it comes to Medicaid work requirements, coverage loss is a feature, not a bug; work requirements are designed to reduce the number of people with Medicaid coverage. That makes it challenging for any state to design a mandatory work requirement in a manner that will avoid coverage losses.

Kentucky’s second waiver approval (which was subsequently blocked by the court) came just two weeks after MACPAC (the statute-created non-partisan federal agency that conducts data analysis for Medicaid and CHIP and makes recommendations to HHS for policy related to Medicaid and CHIP) sent a letter to HHS recommending that disenrollments for failing to comply with the Medicaid work requirement in Arkansas be paused until adjustments could be made to the program to “promote awareness, reporting, and compliance.”

Arkansas was the only state where a Medicaid work requirement had been implemented at that point, and more than 12,000 Arkansas residents had lost their coverage in the first few months after it took effect. The coverage losses in Kentucky were expected to be substantial, with 95,000 fewer people covered under the new waiver if it had been implemented. And that estimate might have been on the low side.

The Trump and Bevin administrations went to great lengths to point out that the lower anticipated enrollment under the waiver could have been due to a variety of factors, including people transitioning to commercial insurance, temporary suspensions, and the elimination of retroactive eligibility. The waiver approval also highlighted the fact that people who don’t comply with the reporting requirements for a Medicaid work requirement are choosing not to comply with the requirements, despite the fact that there are significant concerns that people might not be aware of the reporting requirements or fully understand how to comply with them. But any way you look at it, the point of the Kentucky HEALTH waiver was to reduce the number of people on Medicaid in Kentucky. And there is no mechanism to prevent these individuals from simply joining the ranks of the uninsured once they no longer have Medicaid coverage.

What was Kentucky trying to do with the Kentucky HEALTH waiver?

The Kentucky HEALTH Medicaid waiver was never implemented, despite being approved twice by the federal government. And Governor Beshear officially terminated the waiver as of late 2019. But here’s a summary of the changes the waiver would have made to Kentucky’s Medicaid program for adults age 19-64 (Kaiser Family Foundation has a more detailed summary here):

- Dental and vision services (limited coverage was already provided under Kentucky Medicaid), over the counter medications, and partial reimbursement for gym memberships would have been available via a new system called My Rewards Account. Although the Kentucky HEALTH waiver demonstration was scheduled to take effect in July 2018, Kentucky residents were able to start earning points in their My Rewards Accounts as of April 1, 2018. To earn credit in a My Rewards Account (which could then be used for the aforementioned services), Medicaid enrollees would need to complete various actions such as smoking cessation programs, job training, taking the GED, completing a financial literacy course, or a course on managing chronic health conditions. Although the stated intent was to lift people out of poverty and reduce spending on Medicaid, the proposal was widely panned by public health experts, and dentists question the wisdom of reducing dental benefits in an area where dental disease is widespread.

- A “community engagement” requirement (i.e., a work requirement) applicable to non-disabled Medicaid enrollees aged 19-64, although some populations would have been exempt. Each month, enrollees would have had to complete 80 hours of “community engagement activities,” (a job, job training, education, or community service). Bevin’s administration projected that about 350,000 Medicaid enrollees would have been subject to the community engagement requirement; various populations would have been exempt.

- Enrollees would have had to pay premiums in order to remain enrolled in Kentucky HEALTH. The premiums would have varied based on income, and would have ranged from $1/month to $15/month. Those with income above the poverty level (100 – 138% of the poverty level) who didn’t pay premiums for 60 days would have been locked out of the program for six months.

- Bevin’s administration projected that Medicaid enrollment in the state would have dropped by about 90,000 to 100,000 people as a result of the Kentucky HEALTH program (due in part to the community engagement requirement, but also the new premiums for some enrollees, and the various hoops that enrollees would have had to jump through in order to maintain coverage). Consumer advocates worried that some (many?) of the people who ultimately lost coverage as a result of the community engagement requirement would actually have been eligible for Medicaid under the new rules, but would have been stymied by the reporting requirements and other aspects of proving their eligibility.

- Able-bodied, non-pregnant adults enrolled in Kentucky Medicaid would have had a $1,000 “deductible” but it wouldn’t have worked like regular health insurance deductibles (some media outlets reported this as if members would have had to pay for their first $1,000 in medical costs, but that was not the case). Essentially, non-preventive services would have been tracked against a $1,000 balance in each member’s “Deductible Account.” At the end of the year, up to 50% of the remaining balance of the “deductible” would be transferred to the member’s My Rewards Account. It was an incentive intended to get enrollees to avoid unnecessary care, in order to keep the credit in the deductible account and then transfer some of it over to the My Rewards Account. The waiver approval described the Deductible Account as “an educational tool to encourage appropriate health care utilization” and noted that “the Deductible Account is also likely to prepare beneficiaries to manage their coverage in the commercial market, where plans often impose deductibles.” But enrollees who use up the virtual money in their Deductible Accounts (ie, by receiving non-preventive care during the year) would still have been able to access medical care for the remainder of the year, and no money would have come out of the enrollees’ pockets for this program.

- Retroactive eligibility would no longer have been available for Kentucky HEALTH enrollees, except for pregnant women and former foster care youth. Retroactive eligibility allows people to sign up for Medicaid with an effective date up to three months earlier. This program is particularly useful for hospitals, as it allows them to help uninsured (but Medicaid-eligible) patients to enroll in Medicaid and be covered for the care that they receive as soon as they enter the hospital, rather than having to wait for enrollment to take effect.

- In granting approval for Kentucky’s waiver, CMS noted that “The approval of the waiver of retroactive eligibility encourages beneficiaries to obtain and maintain health coverage, even when healthy. This is intended to increase continuity of care by reducing gaps in coverage when beneficiaries churn on and off Medicaid or sign up for Medicaid only when sick.” However, the new premium requirements and community engagement requirements would have resulted in some people losing access to Medicaid, and hospitals would likely have seen more uninsured patients. Since they wouldn’t have been able to enroll people in Kentucky HEALTH retroactively, the result could have been more uncompensated care for Kentucky hospitals.

While the language of Kentucky’s waiver and the CMS approval letter was couched in positivity (ie, empowering patients, encouraging community engagement, etc.), Bevin’s underlying position all along was that the state couldn’t afford to have half a million new enrollees in its Medicaid program under the ACA, and his objective was to trim the Medicaid roles in Kentucky.

Although Medicaid expansion waivers are certainly better than rejecting expansion altogether, they tend to limit enrollment more than straight expansion. That’s because waivers typically include some way for enrollees to have “skin in the game,” including premiums for some enrollees. But numerous studies have shown that imposing premiums on very low-income people tends to result in fewer people obtaining coverage. And there is no doubt that work requirements also result in fewer people obtaining and maintaining Medicaid coverage — we saw that happen in 2018 in Arkansas.

Kentucky Medicaid history

Despite former Gov. Beshear’s conviction about the benefits of expanding Medicaid, Kentucky did not announce the decision until May 2013. Beshear cited concerns about the cost in explaining why the state’s decision came slower than in other states that adopted expansion. But Beshear strongly advocated for both Medicaid expansion and a state-run marketplace (Kynect). His administration touted both the public health and economic benefits of Medicaid expansion, including improved health outcomes through access to health insurance, the creation of nearly new 17,000 jobs, and a $15.6 billion impact on the state economy over seven years.

The Kentucky legislature did not authorize Medicaid expansion, which was a concern for Senate President Robert Stivers. However, Kentucky’s Medicaid eligibility rules are defined in state regulations, which can be changed by executive order. Accordingly, legislative approval was not needed.

While Kentucky Medicaid expansion was secure during its first couple of years, analysis by the Rockefeller Institute indicated that the lack of legislative approval could leave the program in jeopardy after Beshear left office. That is exactly the scenario the state encountered when Governor Bevin’s administration took over.

Bevin would have been able to roll back Medicaid expansion without legislative action, although he backed off from that tactic very early on, favoring an 1115 waiver to make changes to the existing program instead. The Trump administration twice approved Kentucky’s waiver proposal (which hinged in large part on a work requirement for able-bodied adults enrolled in Medicaid), but a federal judge blocked implementation of the program and Gov. Andy Beshear officially rescinded the work requirement in late 2019.

Kentucky lawmakers continued their efforts to implement a Medicaid work requirement, however, and enacted legislation in 2022 that directed the state to create a new work requirement. Federal approval won’t be granted under the Biden administration, but could be granted by a future administration.

Louise Norris is an individual health insurance broker who has been writing about health insurance and health reform since 2006. She has written dozens of opinions and educational pieces about the Affordable Care Act for healthinsurance.org.

Looking for more information about other options in your state?

Need help navigating health insurance options in Kentucky?

Explore more resources for options in Kentucky including ACA coverage, short-term health insurance, dental insurance and Medicare.

Speak to a sales agent at a licensed insurance agency.

Footnotes

- “October 2024 Medicaid & CHIP Enrollment Data Highlights” , Medicaid.gov, Accessed January 2025 ⤶

- “Medicaid Enrollment – New Adult Group”, Medicaid.gov, Accessed February 2025 ⤶

- “MEDICAID PUBLIC HEALTH EMERGENCY UNWINDING” , khbe.ky.gov, Accessed January 2025 ⤶

- “Total Monthly Medicaid & CHIP Enrollment and Pre-ACA Enrollment”, KFF.org, Accessed February 2025 ⤶