Efforts to repeal the Affordable Care Act have run into political trouble. Crowds are berating Republican legislators at angry town halls. President Trump’s poll numbers are sinking. For the first time, the majority of Americans express support for ACA, too. Efforts to roll back ACA’s Medicaid expansion have proved particularly difficult. Democratic and Republican Governors oppose the idea. So do many other key constituencies.

The politics have changed after November 8 because the real choices are starkly before us: If ACA is repealed, what will actually happen to millions of vulnerable Americans who rely on ACA for essential health care and coverage?

Facing these stark questions, some conservatives bluntly maintain that we should snatch health coverage from millions of people: Insuring poor people just isn’t worth it. Those espousing such views deserve some credit for candor. But the brutality of their argument makes it politically self-immolating.

So the search is on for kinder and gentler talking points against the ACA. In a creative bit of political jujitsu, conservatives argue that Obamacare itself harms the vulnerable, and that we must repeal ACA to really help the most deserving.

We’ve seen these arguments before. The low-rent version is that Obamacare seeks to kill off the elderly and the disabled through death panels. A slightly more sophisticated version holds that having a Medicaid card is worse than being uninsured. Spoiler alert: It’s not.

GOP’s new argument to un-cover low-income adults

A new brazen argument seems to be making the rounds. On this account, ACA’s Medicaid expansion for able-bodied poor people harms the most vulnerable by siphoning away state funds that would otherwise finance more important disability services. If you aren’t steeped in Medicaid or disability policy, this argument sounds pretty plausible: States are robbing Peter to pay Paul, when Peter is more needy and deserving.

Consider this article about Arkansas’ Medicaid expansion by conservative commentator Nicholas Horton. Horton argues that the most needy Arkansans “have been pushed to the back of the line since the state expanded Medicaid to able-bodied adults:”

One of those Arkansans is a little girl named Skylar Overman. Skylar has a rare neurological condition that requires around-the-clock care. But Skylar has spent nearly her entire life on a Medicaid waiting list for needed services. In fact, she moved down the list nearly 100 spots in 2016.

Unfortunately, Skylar is not alone. There are nearly 3,000 Arkansans who, like her, are stuck languishing on the waiting list. Since the state expanded Medicaid under ObamaCare, the waiting list has grown by nearly 700 people, while 79 individuals with developmental disabilities have died before ever getting the care they needed.

Skylar Overman certainly deserves better. I’m glad to see Arkansas has made recent progress on this front. Still, I’m baffled that Horton or anyone else would blame Ms. Overman’s difficulties on the ACA.

The state’s long disability wait lists have been a sensitive issue for many years. Indeed, Arkansas has long been rated as one of America’s worst places for people with disabilities. The year ACA was passed, Arkansas ranked #50 in United Cerebral Palsy’s assessment of intellectual and developmental disability services. It now ranks #49.

To add insult to injury, Arkansas’s emphatic Republican legislature rejected ACA funds (from the Community First Choice Option) which are specifically intended to reduce disability wait lists and to improve community-based services. Arkansas also recently passed a $50 million tax cut.

This issue and this misleading talking point go beyond this one troubled state. So it’s worth unpacking things a bit.

Expansion did the opposite of short-changing disabled

Let’s start with something basic. In Arkansas and every other expansion state, the federal government now covers about 95 percent of the spending associated with Medicaid expansion. That will taper down to 90 percent, which is still pretty much the most generous federal match I’ve ever seen. For reasons I don’t understand, Mr. Horton’s column doesn’t mention this number or trace its implications.

Even that 90- or 95-percent figure understates the true subsidy to expansion states. Many states use Medicaid expansion dollars to finance services they would otherwise finance themselves. States have also covered Medicaid recipients through the expansion they would otherwise have had to serve in more costly ways.

Only last year, Arkansas’s Republican Gov. Asa Hutchinson warned his state legislature that rejecting Medicaid expansion would require painful cuts to foster care and other important services. Since Election Day, Republican governors such as Ohio’s John Kasich and Illinois’s Bruce Rauner have been surprisingly vocal in their efforts to educate the public and Congress on these realities.

Expansion dollars also keep the lights on at safety-net providers that serve the disabled. ACA has markedly reduced uncompensated care burdens at public hospitals, substance use disorder clinics, and other providers mainly financed by local government. Such support allows providers, states, cities, and counties to expand services and to finance other disability programs. States are testing new Medicaid models to improve services to vulnerable populations such as individuals with severe mental illnesses. Many such efforts are now on-hold, as people wait to see what actually happens to ACA.

Now there is always the possibility that Congress might screw things up by repealing the Medicaid expansion, block-granting Medicaid or by reducing the federal government’s matching rate. These are risks created by a reckless Congress, not inherent defects of ACA.

Disability groups among expansion’s strongest allies

If Mr. Horton and his colleagues were right, one would expect disability advocacy groups to criticize ACA’s Medicaid expansion, and to clamor for it to be clawed back. Instead, the disability community ranks among the expansion’s strongest political and legal allies. The Arc, America’s most prominent advocate for people with conditions such as Down syndrome, notes that “Thanks to the Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act, millions of people, including people with disabilities, their family members, and their support professionals, have gained access to health coverage. Lives have been saved because people have had access to affordable, comprehensive health coverage.”

Disability groups take a strong stand because Medicaid expansion serves millions of people who live with disabilities and chronic conditions. Many people living with disabilities are low-income workers. Indeed there is some evidence that Medicaid expansion allows people with disabilities to remain in the paid work force.

Medicaid expansion fills the gap because many people with disabilities do not participate in federal disability programs. Suppose, for example, you are a part-time cashier. You use a wheelchair, and you earn $10/hr. You really need ACA’s Medicaid expansion. Or suppose you are a dishwasher in downtown Chicago with poor vision or that you have an IQ of 72. You might well need Medicaid expansion, too. Maybe you’re disabled due to addiction, which is not qualifying conditions for federal disability programs. Or maybe you’ve actually qualified for federal cash disability benefits. You might still need ACA’s Medicaid expansion, because there is a two-year waiting period before you actually receive Medicare health coverage.

Illnesses and injuries matter, too. A brilliant New York Times story describes how, before ACA’s Medicaid expansion, uninsured gunshot victims in cities such as Chicago and Detroit sometimes walked around with pieces of skull missing or unnecessary colostomy bags because they could not gain access to needed surgery. Medicaid expansion dramatically reduced these problems.

A freeze designed to slow ACA’s momentum

Mr. Horton and others favor an enrollment freeze to slow the political momentum of ACA’s trend to near-universal coverage. This won’t save states money compared with what they receive right now. Republicans may hope that such a freeze, rather than a move to snatch coverage from current recipients, will avoid politically self-immolating images of sympathetic human beings losing their insurance. Good luck keeping next year’s gunshot victims and diabetes patients off the evening news.

Almost without anyone noticing, ACA established the principle that the sick and injured are entitled to decent medical care. The young girl on home nursing, the cashier in the wheelchair, the gunshot victim, and the minimum-wage dishwasher are equal citizens, each worthy of help.

As a matter of political strategy, I understand why ACA’s opponents might seek to divide Americans with disabilities from other Medicaid recipients. I don’t think this will work. Curtailing Medicaid expansion certainly won’t improve disability services. Instead, it will make them worse.

Curtailing expansion doesn’t match the values of the disability community, either. Social insurance is about having each other’s backs. No one understands that better than people who live every day with disabilities and their loved ones. We must protect each other from calamities and life risks that would crush any one of us, if we had to face them alone. After Election Day, that’s what the ACA debate is really about. That’s also why, to the surprise of many, ACA is proving surprisingly difficult to repeal.

Harold Pollack is the Helen Ross Professor at the School of Social Service Administration. He is also Co-Director of The University of Chicago Crime Lab. He has published widely at the interface between poverty policy and public health. Pollack serves as a Fellow at the MacLean Center for Clinical Ethics at the University of Chicago, and as an Adjunct Fellow at the Century Foundation.

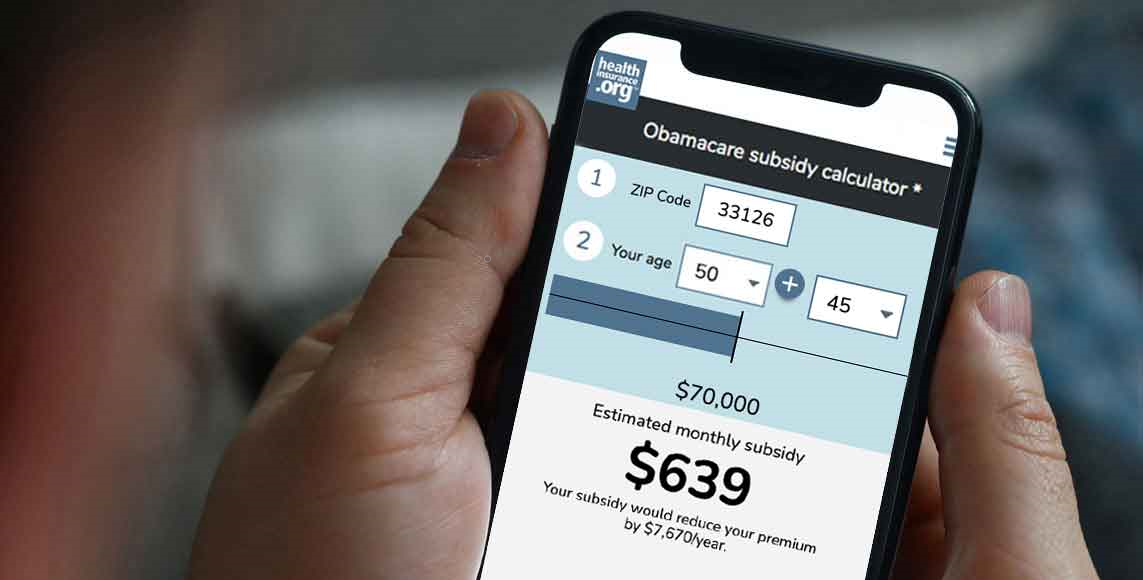

Get your free quote now through licensed agency partners!