If you go by the standard conservative talking-points, Medicaid must be the worst insurance in America. The Manhattan Institute’s Avik Roy even wrote maybe 2,000 columns and a little e-book promoting this theme.

Most recently, in last week’s Republican debate, Carly Fiorina earned her second Politifact “Pants on Fire” with her statement that “Obamacare isn’t helping anyone.” Presumably to explain away the greatest decline in the uninsured since the 1960s, Fiorina argued, “We’re [just] throwing more, and more people into Medicaid.”

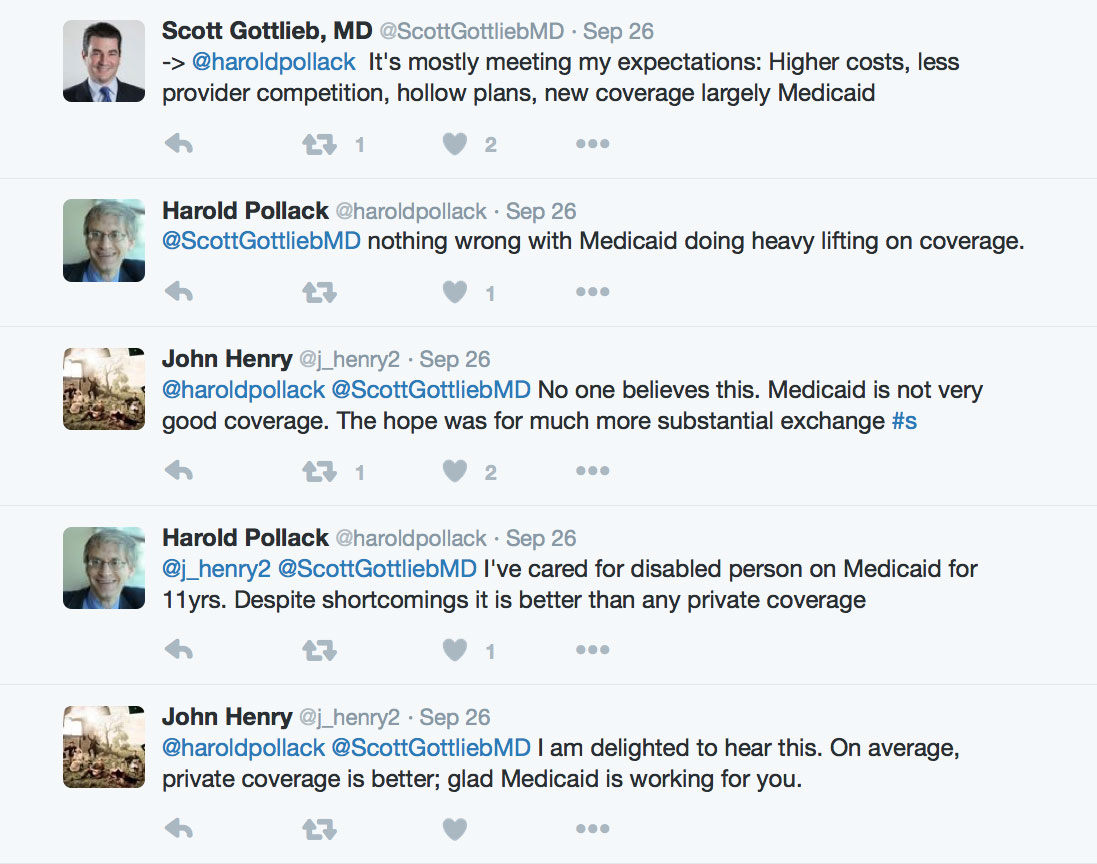

I’ve tangled with many people about this question, for example in this fairly typical Twitter exchange:

Click to see larger version.

Such criticism doesn’t come from nowhere. My wife and I don’t need Twitter mansplainations to know that Medicaid undermines access by underpaying providers, or that Medicaid has other problems. We’ve relied on Medicaid to care for her brother Vincent many years now.

Still, the fact is that Medicaid compares surprisingly well with private insurance in patient satisfaction and in other key measures. Aaron Carroll and Austin Frakt lament “Zombie Medicaid arguments” which criticize the program based on stereotypes or misinterpreted studies.

JAMA Pediatrics survey: Medicaid gets a bad rap

Which … brings us to this week’s study in JAMA Pediatrics, “Quality of Health Insurance Coverage and Access to Care for Children in Low-Income Families,” by Amanda Kreider and her colleagues.

These researchers examined 2003-12 data concerning 80,655 children collected in the National Survey of Children’s Health. All of these children came from households reporting pretty modest annual incomes, between 100 percent and 300 percent of the federal poverty line. That’s roughly between $20,000 and $60,000 for a family of three. Fifty-seven percent of the children relied upon private insurance. Eighteen percent were covered through the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP). Fourteen percent relied on Medicaid. Eleven percent were uninsured.

Kreider and colleagues examined the impact of insurance on many parent-reported outcomes: access to and use of primary and specialty care, unmet health care needs, out-of-pocket costs, effective care coordination, and satisfaction with care. Their methodology was quite simple as research papers go. They performed standard statistical adjustments to account for differences in household income, child age, gender, race, and other characteristics. They then computed predicted probabilities of each outcome corresponding to the same child being (a) uninsured, (b) receiving Medicaid, (c) receiving CHIP, or (d) holding private insurance.

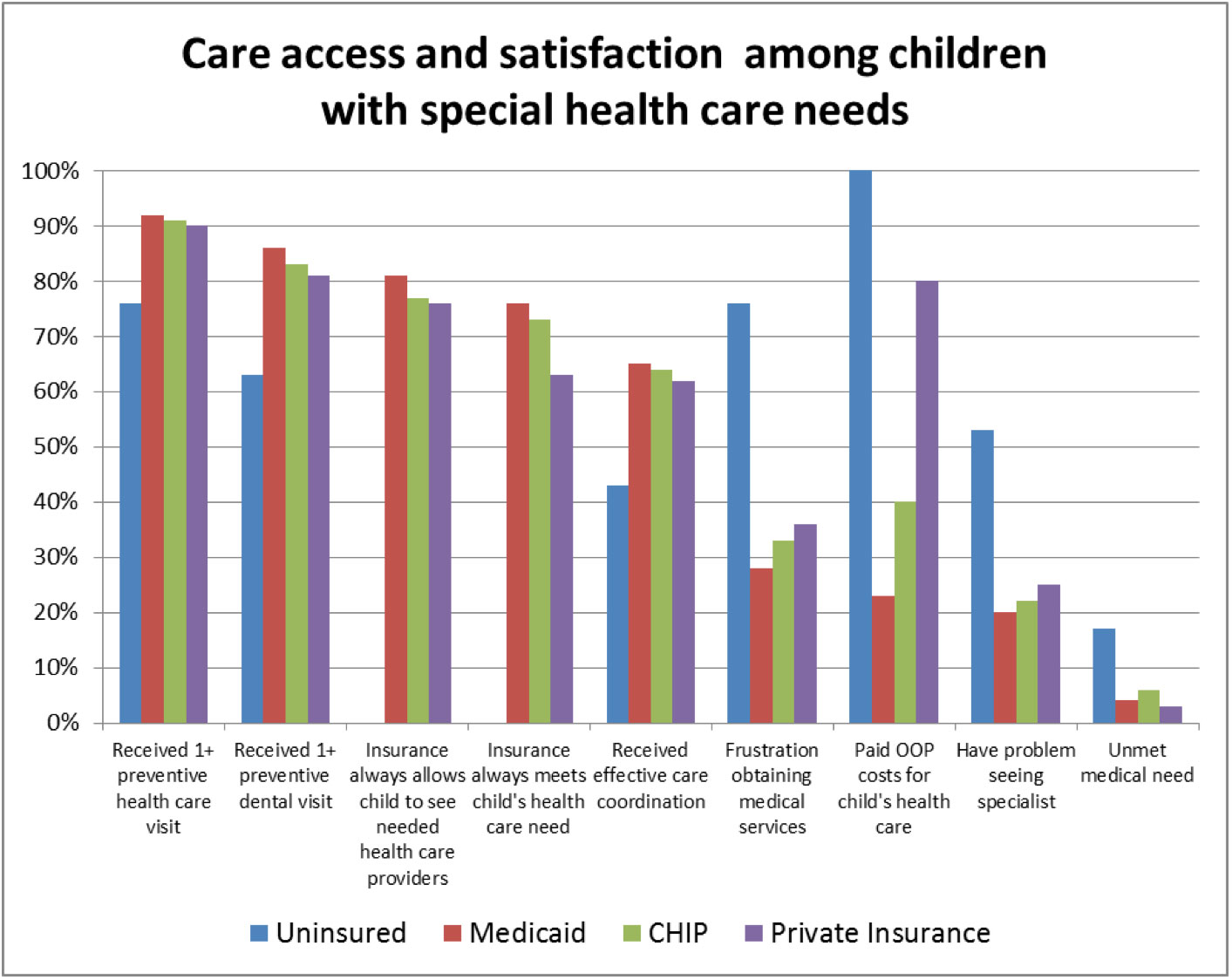

I’ve graphed some of their main results for children with special needs (CSHCN) below.*

Their results – alongside others – underscores two points.

When it comes to children with special health care needs, Medicaid is often better than the available public or private alternatives. The program could obviously be improved. Then again, so could these other forms of insurance coverage.

Serving kids with special health care needs

The first is precisely what faithful readers would expect me to say. Medicaid gets a really bad rap. When it comes to children with special health care needs, Medicaid is often better than the available public or private alternatives. The program could obviously be improved. Then again, so could these other forms of insurance coverage.

For ten out of 14 access and satisfaction measures, parents of children with health care needs rated Medicaid better than private insurance. (Private insurance was rated better on two remaining categories, in each case by one percentage point. Two outcomes were tied.)

Not surprisingly, having any form of insurance was vastly better than being uninsured in this population. Medicaid was also ranked at least slightly superior to CHIP on all 14 measures.The most concerning differences arose in out-of-pocket costs. Medicaid recipients were much less likely to face these burdens than were those with other forms of coverage.

Scores were closer within the whole population of (mostly-healthy) kids. Medicaid only beat out private coverage by a score of 7-4, with three ties. Yet the overall pattern was pretty similar, especially in preventive care.

Medicaid offers more comprehensive long-term disability services and supports than Medicare or private insurance does. Medicaid has fewer hidden traps or unexpected out-of-pocket payments. It is really designed for low-income people. State Medicaid programs also have decades of experience serving children and adults living with disabilities. Medicaid-funded providers have often pioneered integrated care models and the use of team care, providing the foundation for Accountable Care Organizations and related integrated care efforts.

Medicaid is also designed with some attention to social determinants of health and child development. For example, Medicaid has a long history of providing school-based services for children who require these supports. Medicaid’s Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic, and Treatment (EPSDT) program covers a rather remarkable range of important services for low-income children and those with special needs.

Filling gaps in marketplace coverage

My second point is less of a fan-boy comment about ACA. I’m quite concerned about the capacity of the new state marketplaces to serve children with significant health problems.

Marketplaces will serve many children (and adults) with special health care needs. And qualified health plans (QHPs) are required to cover pediatric services as an essential health benefit. Yet as Kreider and her colleagues note, a recent review of state benchmark plans (on which QHPs are based) indicated that none of the benchmark plans specifically delineated which pediatric services must be covered. QHPs are modeled after employer plans, which have traditionally provided limited coverage for children with special health care needs.

Grace and colleagues note a disturbing pattern by which some QHPs exclude coverage for pediatric developmental and mental health services. Many excluded categories concern habilitative services, that is “health care services that help a person keep, learn, or improve skills and functioning for daily living.” Habilitative services include speech therapy, many forms of physical and occupational therapy, services for autism or developmental delays, and related services designed to promote healthy development. Many such services (though not all) are typically reimbursed by Medicaid.

This is a huge concern for many children who require habilitative therapies and specialty care – not to mention those who require new wheelchairs, durable medical equipment, or many other things. QHPs also routinely impose much higher cost-sharing than is found within Medicaid. Their provider networks may or may not encompass important pediatric specialties.

We don’t yet know how marketplaces will work for children with special healthcare needs, or how private insurance plans should harmonize what they offer to match Medicaid and CHIP. With so many contentious political, policy, and clinical issues in-play, policymakers, clinicians, and advocates have not given these issues their due. It’s time they do. Medicaid’s best efforts provide a valuable foundation for these efforts.

* I added one bar, assuming that 100 percent of the uninsured are responsible for out-of-pocket payments for medical services.

Harold Pollack is Helen Ross Professor of Social Service Administration, and Faculty Chair of the Center for Health Administration Studies at the University of Chicago. He has written about health policy for the Washington Post, New York Times, New Republic, The Huffington Post and many other publications. His essay, “Lessons from an Emergency Room Nightmare,” was selected for The Best American Medical Writing, 2009.

Get your free quote now through licensed agency partners!