Over the weekend on Twitter, I encountered a heartwarming picture of House Speaker Paul Ryan in cordial conversation with teenagers who have apparently survived childhood cancer.

Advocacy is not limited to adults. These Wisconsin teens shared some powerful stories with me about their fight against childhood cancer. pic.twitter.com/VJ0eQDXu7U

— Paul Ryan (@SpeakerRyan) April 27, 2017

That photo-op is unfortunate, since Speaker Ryan’s healthcare bill, the American Health Care Act, would allow states to waive Affordable Care Act protections that bar insurers from charging higher premiums to childhood cancer survivors. AHCA would also allow states to weaken essential health benefit provisions required to ensure that insurance actually works when one becomes seriously ill, and which make it harder for insurers to discourage sick people from staying with their plans.

Childhood cancers are thankfully rare, but many millions of us still have a stake in this issue. Before ACA, about four million Americans were medically uninsurable: They were uninsured and had been diagnosed with cancer, stroke, diabetes, heart attack, or similar serious conditions. An estimated 18 percent of applicants were denied coverage on the individual health insurance market.

Rollback of protections: monumentally unpopular

That figure didn’t count those with pre-existing conditions who didn’t bother to apply. Millions more were forced to pay higher premiums because of similar factors. Currently, an estimated 27 percent of American adults have been diagnosed with declineable preexisting conditions.

One of the ACA’s main achievements was to end these practices, and to prohibit the business model by which insurers sought to cherry-pick the healthiest people, while excluding or charging hefty additional premiums to other consumers. More than 80 percent of the American public supports ACA’s protections for people with preexisting conditions.

AHCA, which would roll back these protections, is monumentally unpopular, supported by only 17 percent of Americans. It would provide funds for high-risk pools and other efforts to ostensibly address these issues. But none of the pertinent provider or patient advocacy groups believes these measures are adequate.

The American Medical Association opposes the bill. So does the AARP, Catholic health care providers, and the American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network oppose these provisions, as they oppose other aspects of AHCA, including a more than $800 billion Medicaid cut, and reduced affordability subsidies for people with low and modest incomes on the ACA marketplaces – all largely instituted to implement a regressive tax cut.

We don’t have a Congressional Budget Office score of the latest House bill. We don’t have that score for a reason: because AHCA received a devastating CBO score last time around. So Republicans are hoping to vote before that score is available. This is an incredibly rushed and slipshod approach to reforming our $3 trillion health care system.

Health history back under the microscope

There’s another problem, too, which is both obvious and easy to overlook: By allowing states to waive preexisting condition protections, AHCA would allow insurers to restore a practice called “medical underwriting” to rummage through your private business in ways that most Americans find intrusive and revolting.

If you’re lucky, you may never have had the charming experience of completing a medical underwriting form. I happen to live in Illinois. Here is my state’s pre-ACA standard health insurance application. Five pages of health questions cover everything from heart attack and cancer to acne, attention deficit disorder, and strep throat.

If you’ve put on any medical mileage, you won’t be the super-preferred category offered the lowest rates. And the repercussions go beyond your checkbook. You’ll also be forced to reveal some of your most intimate or difficult personal experiences to some insurer that may not have your best interests at heart. Maybe it’s a scary illness you once experienced. Maybe it’s a sexually transmitted infection, or a laboratory test suggesting you are at heightened risk of diabetes or stroke. If it’s bad enough, you might be shunted over to some high-risk pool, whose terms and financing remain to be determined. If it’s less serious, you’ll likely pay more and potentially experience other difficulties.

Stigma and shame in the pre-ACA world

Like millions of others, my particular story would involve mental health. Back in high school. I was attacked in the subway by a group of kids who knocked me to the ground, grabbed me by the hair, kicked me in the face, and smashed my head against a concrete floor until I yielded my watch, which had been a birthday present from my girlfriend. I escaped serious physical injury, but I was pretty traumatized. A week or so later, I went to my pediatrician and complained of headaches. He roughly examined my scalp. Finding no additional bruises, he reassured me that it was probably just a mental thing, and sent me packing.

The incident cast a painful shadow. For years I was more angry and fearful than I needed to be. Yet for years, I never mentioned this mental pain to any medical provider. I finally received valuable help when I was in my mid-twenties. I regret waiting to pursue that help until my difficulties had largely abated.

If you ask why I delayed, I’m not sure I could give a candid answer. Part of the answer resides in the stigma and shame I experienced over the incident and my traumatized reaction to it. Part of the answer is more basic: I didn’t particularly want anyone to know that I had required mental health services. I felt an inchoate but real fear that the accompanying paper trail would somehow come back to haunt me.

Americans will avoid seeking mental health care

I’ve never been asked about this on any health insurance form. But in the pre-ACA world, it was rational to believe that I might be. “Have you ever been treated for depression” was a standard medical underwriting question, along with the obvious follow-ups asking whether you were hospitalized, whether your depression was merely “situational,” and more. If we allow health insurers to once again ask these questions, many Americans will understandably avoid seeking mental health care.

A few months ago, one of my friends lost her mom under harrowing circumstances. I suggested that she might seek some grief counseling. As we talked, I could sense her wheels turning, wondering if she really wanted to do this. The revolting idea that some insurer might someday use that information against her provides one more barrier, one more reason for ambivalent or embarrassed patients to hesitate before seeking help for real mental pain.

For no obvious policy reason, in response to no obvious public demand, Speaker Ryan and his colleagues would restore that barrier, which has been effectively addressed by the ACA. Do we really want to treat each other that way? I think not.

Harold Pollack is Helen Ross Professor of Social Service Administration, and Faculty Chair of the Center for Health Administration Studies at the University of Chicago. He has written about health policy for the Washington Post, New York Times, New Republic, The Huffington Post and many other publications. His essay, “Lessons from an Emergency Room Nightmare,” was selected for The Best American Medical Writing, 2009.

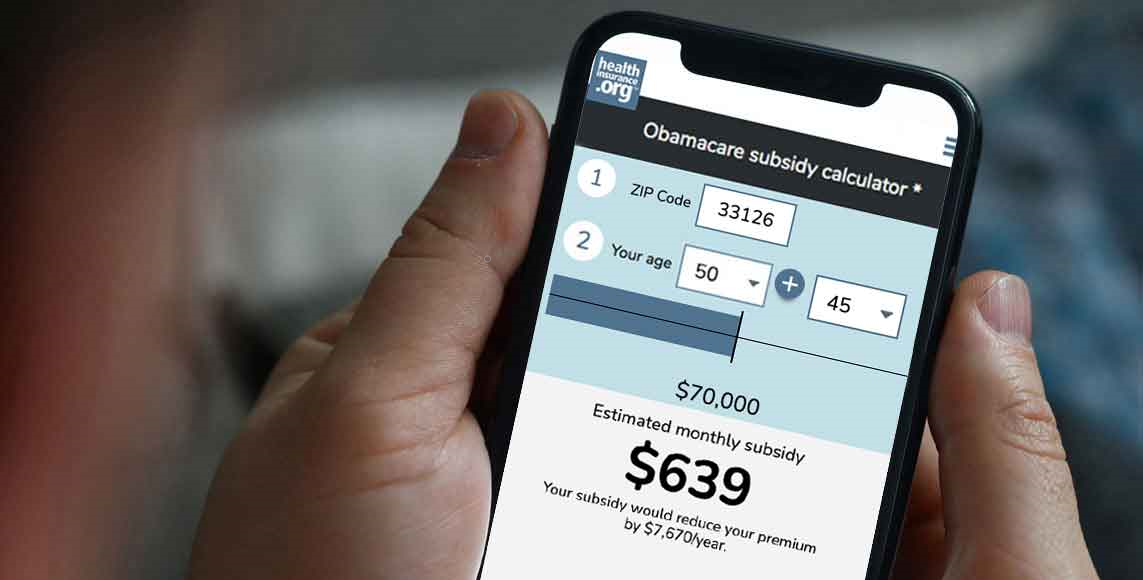

Get your free quote now through licensed agency partners!