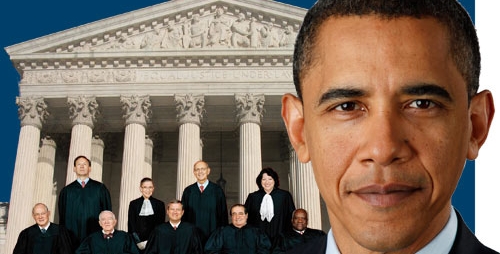

Today, the Supreme Court begins to hear three days of oral arguments on the legal challenge to President Barack Obama’s health care reform legislation brought by 26 states and one business organization (The National Federation of Independent Business). The case raises three issues:

- Does the constitution give Congress the power to require that all Americans buy health insurance – or pay a penalty?

- If the mandate that they purchase insurance is unconstitutional, can the rest of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act stand, including the provision that insurers must cover everyone?

- Does the federal government have the right to tell the states that they must expand Medicaid to cover all adults with family incomes below 133 percent of the poverty level – or lose all federal Medicaid funding?

For months, the media has been feasting on the story, calling it "The Case That Could Change Health Care Forever."

Yesterday, the Baltimore Sun declared that "The most important six hours of recent American history will start to unfold on Monday."

No question, the story is sizzling. And I hate to be a wet blanket. But let me suggest that the hullaballoo is totally unwarranted.

Why the law won't be overturned

I cannot believe for a minute that this Court wants to go down in history as the Gang of Nine that quashed the most important piece of legislation that Congress has passed in 47 years. If it did, we could find ourselves on the brink of a constitutional crisis. It is simply not up to the Supreme Court to rewrite legislation passed by Congress.

Moreover, as the Justice Department argues, the mandate which says that everyone must purchase insurance cannot be separated from the very popular provision which insists that insurers cover everyone without inquiring about pre-existing conditions. Overturn one and you must repeal the other.

Otherwise many people would not buy insurance until they fell ill, secure in the knowledge that insurers could not charge them more because they were sick. The insurance pool would be filled with the aged and disabled, and premiums would skyrocket to unacceptable heights. It's not clear how the system could survive, but the Court knows that the provision which says that insurers can no longer shun the sick enjoys widespread public support. They would be loathe to throw it out, which suggests that they will keep the mandate.

A credibility risk

Finally, if the Court strikes down the Obama administration's signature legislation, just months before the November election, it risks undermining its own credibility, shredding what is left of its reputation for political neutrality. This court is concerned about its legacy.

As Dahlia Lithwick recently pointed out on Slate.com: "The current court is almost fanatically worried about its legitimacy and declining public confidence in the institution. For over a decade now, the justices have been united in signaling that they are moderate, temperate, and minimalist in their duties ..."

"That means the court goes into this case knowing that the public is desperately interested in the case, desperately divided about the odds, and deeply worried about the neutrality of the court," she writes.

Lithwick then points to a Bloomberg News national poll "showing that 75 percent of Americans expect the decision to be influenced by the justices’ personal politics.”

I very much doubt that the Court wants to confirm this jaded view of the highest court in the land.

"Justice Clarence Thomas doesn't worry much about things like that," Lithwick adds. "I suspect Chief Justice Roberts and Justice Kennedy worry quite a lot."

'Radical decision' would affect many federal programs

Health reform's opponents are asking the Court to make decisions that Washington and Lee Law Professor Timothy Jost calls "truly radical": If the court ruled against Medicaid expansion it could affect "many federal programs, and not just health care programs" that "operate through conditional grants to the states," Jost warns. "It would open every one of these programs to judicial challenge."

As for the notion that Congress cannot fine individuals who refuse to buy insurance, the penalty is, in effect a tax, observes Yale Law School’s Jack Balkin, and “if taxes that act as incentives to engage in socially desirable behavior and reduce the costs of government programs are unconstitutional, much of our tax system would be constitutionally suspect.”

If some find the legislation unacceptable, they have remedies – but the Supreme Court is not one of them. As Christian G. Kiely explains in the Suffolk University Law Review: "If the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act is an ill-conceived law, the opposition should seek resolution through the political process and not the courts."

Kiely quotes Yale's Balkin: "Whether or not such a law is wise, the people's representatives have the constitutional authority to enact it. What was said during the constitutional struggle over the New Deal is still true today: for objectionable social and economic legislation, however ill-considered, 'appeal lies not to the courts but to the ballot and to the processes of democratic government.'"

Maggie Mahar is an author and financial journalist who has written extensively about the American health care system. Her book, Money-Driven Medicine: The Real Reason Health Care Costs So Much, was the inspiration for the documentary, Money Driven Medicine. She is a prolific blogger, writing most recently for TIME's Moneyland. Previously she wrote and edited the Health Beat blog for the progressive think tank, The Century Foundation. She also recently provided background on Congressional health care legislation for HealthReformVotes.org, a special project of the Health Insurance Resource Center.