Medicaid eligibility and enrollment in Tennessee

In 2024, Tennessee expanded Medicaid eligibility for low-income parents to 105% FPL, up from 89%

Who is eligible for Tennessee Medicaid?

Tennessee Medicaid (TennCare) is available to the following legally-present Tennessee residents, contingent on immigration guidelines1 (these income levels include a built-in 5% income disregard)2

- Adults with dependent children, if their household income doesn’t exceed 105% of poverty. This is the highest threshold in the country among states that have not expanded Medicaid.3 Tennessee previously had a lower income limit for parents and caretakers, but received permission from CMS to increase it in mid-2024 (to 100% FPL, which ends up being 105% after the 5% income disregard is applied). The waiver approval also allows Tennessee to cover the cost of up to 100 diapers per month for infants under the age of two who are enrolled in TennCare.4

- Pregnant women and infants under one, with household income up to 200% of poverty. (Tennessee extended postpartum Medicaid coverage starting in 2022, so that coverage for the mother continues for 12 months after the baby is born, instead of terminating after 60 days.)

- Children age 1 – 5 with household income up to 147% of poverty, and children 6 – 18 with household income up to 138% of poverty.

- CHIP (Cover Kids) is available to children with household incomes too high for Medicaid, up to 255% of poverty.

Apply for Medicaid in Tennessee

You can enroll online at HealthCare.gov. You can also enroll by phone at 1-800-318-2596 (HealthCare.gov phone support). Or you can apply in person or by mail at your local County Social Services Office.

Eligibility: Parents with dependent children are eligible for Medicaid with household incomes up to 105% of poverty. Children are eligible for Medicaid or CHIP with household incomes up to 250% of poverty, and pregnant women are eligible with incomes up to 195% of poverty.

ACA’s Medicaid expansion still not implemented in Tennessee

Tennessee is one of ten states where Medicaid expansion has not been implemented as of 2025. As a result, an estimated 95,0005 Tennessee residents in the coverage gap — ineligible for Medicaid and also ineligible for premium subsidies in the exchange. This group is comprised of non-disabled adults with income below the poverty level and without minor children (there is no longer a coverage gap in Tennessee for parents of minor children, due to the state’s expansion of the eligibility rules for this population in 2024).4

If the state were to expand Medicaid, an estimated 150,000 people would gain access to coverage, and the state would save money due to the enhanced federal funding that comes with Medicaid expansion.6

Legislation introduced in early 2025 would authorize Tennessee’s governor to expand Medicaid under the ACA.7 But similar bills were introduced in 2024, and none were successful.8 Similar legislation did not advance in the 2023 session, and neither did bills that directly called for Medicaid expansion.9

Current Tennessee law prevents the governor from expanding Medicaid unilaterally, without the consent of the legislature, but Tennessee Governor Bill Lee has remained opposed to Medicaid expansion, so legislation simply removing the current ban on governor-directed Medicaid expansion might not change anything even if it were to be enacted.10

Medicaid expansion in Tennessee has been a non-starter for most Republican lawmakers. Instead, GOP lawmakers voted in 2018 to impose a work requirement on low-income parents who were already eligible for Tennessee Medicaid, using TANF funding to cover the cost of implementing the work requirement (see details below). But the work requirement was not approved by the federal government, and was never implemented.

And as noted above, Tennessee did seek and receive federal permission to expand Medicaid eligibility for low-income parents starting in mid-2024. As a result, there is no longer a “coverage gap” for parents of minor children, as they are eligible for Medicaid with a household income up to 105% FPL, and are eligible for Marketplace subsidies above that income level.4

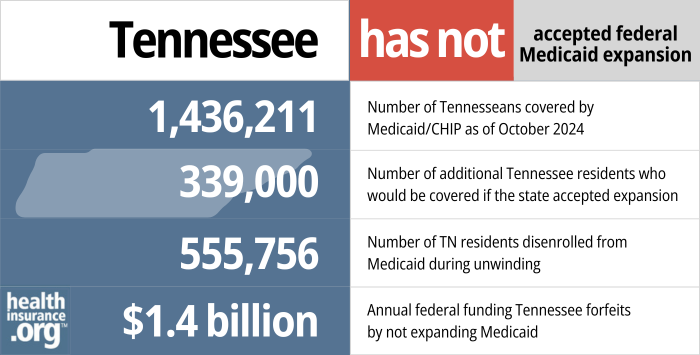

- 1,436,211 – Number of Tennesseans covered by Medicaid/CHIP as of October 202411

- 150,000 – Number of additional Tennessee residents who would be covered if the state accepted expansion6

- 555,756 – Number of TN residents disenrolled from Medicaid during unwinding12

- $1.4 billion – Annual federal funding Tennessee forfeits by not expanding Medicaid (Tennessee would also receive an additional $900 million over two years due to ARP incentive)13

Explore our other comprehensive guides to coverage in Tennessee

We’ve created this guide to help you understand the Tennessee health insurance options available to you and your family, and to help you select the coverage that will best fit your needs and budget.

Hoping to improve your smile? Dental insurance may be a smart addition to your health coverage. Our guide explores dental coverage options in Tennessee.

Use our guide to learn about Medicare, Medicare Advantage, and Medigap coverage available in Tennessee as well as the state’s Medicare supplement (Medigap) regulations.

Short-term health plans provide temporary health insurance for consumers who may find themselves without comprehensive coverage.

Frequently asked questions about Tennessee Medicaid

How do I enroll in Medicaid in Tennessee?

Enrollment in TennCare is year-round; you do not need to wait for an open enrollment period if you’re eligible for Medicaid

- You can enroll online via TennCare Connect.

- Tennessee uses the federally-run insurance marketplace, so you can begin the application process through HealthCare.gov or use their call center at 1-800-318-2596. (Use this option if you are under 65 and don’t have Medicare.) If they determine that you’re likely eligible for Medicaid, they will forward your information to TennCare.

- You can go to any of the state’s 95 Department of Human Services offices to apply in person. You can also use the “find local help” link on HealthCare.gov to find someone in your community who can help you enroll.

- You can print a paper application (Spanish version here, and pages for additional family members are available here) and submit it to your local Department of Human Services office (click here for contact information).

How does Medicaid provide financial assistance to Medicare beneficiaries in Tennessee?

Many Medicare beneficiaries receive Medicaid’s help with paying for Medicare premiums, affording prescription drug costs, and covering expenses not reimbursed by Medicare – such as long-term care.

Our guide to financial assistance for Medicare enrollees in Tennessee includes overviews of these benefits, including Medicare Savings Programs, long-term care coverage, and eligibility guidelines for assistance.

How did Tennessee handle Medicaid renewals after the pandemic?

During the COVID pandemic, from March 2020 through March 2023, states were prohibited from disenrolling anyone from Medicaid, even if their circumstances changed and they no longer met the eligibility guidelines. But that rule ended March 31, 2023, and states then began disenrolling people from Medicaid if they were no longer eligible or if they failed to respond to a renewal notification.

By May 2024, at the end of the year-long “unwinding” period, nearly 556,000 people had been disenrolled from TennCare, but coverage had been renewed for more than 831,000 other enrollees who continued to meet the eligibility guidelines.12

TennCare representatives gave a presentation to state lawmakers in late January 2023, outlining their plans for “unwinding” from the pandemic-era continuous coverage rule and a return to normal Medicaid operations. TennCare enrollment grew by about 22% during the pandemic, with about 1.77 million people enrolled as of early 2023. The state expected that to top out a little below 1.8 million people in the spring of 2023, and then gradually decline back to pre-pandemic levels (roughly 1.4 million enrollees) by mid-2024, although TennCare officials noted that there was a lot of uncertainty in that projection.

By September 2024, total TennCare enrollment stood at about 1.44 million people14 — quite close to what the state had projected.

Data for people who were no longer eligible for TennCare was transferred to HealthCare.gov, the federally-run health insurance Marketplace that’s used in Tennessee, to facilitate enrollment in private coverage (for those not eligible for employer-sponsored coverage).

CMS reported that 123,844 Tennessee residents transitioned from Medicaid to a Marketplace plan during the unwinding period (through April 2024).15

Tennessee Medicaid History and Details

Block grant Medicaid funding was approved in early 2021, but CMS subsequently required TennCare to revert to a per-member-per-month funding methodology

In January 2021, just days before the end of President Trump’s presidency, CMS announced that Tennessee’s Medicaid block grant waiver proposal had been approved. The waiver approval, which is valid for ten years (much longer than typical 1115 waiver approval periods), was intended to allow Tennessee to be the first state in the nation to utilize a block grant approach to federal Medicaid funding. Puerto Rico has long used a block grant funding model for Medicaid, which has led to significant funding shortfalls in the territory’s Medicaid program.

A few months later, in April 2021, a lawsuit was filed by several Tennessee Medicaid beneficiaries, a physician, and the Tennessee Justice Center. The lawsuit (McCutchen v. Becerra) alleged that HHS exceeded its statutory authority when it authorized the TennCare III waiver proposal, that the authorization was arbitrary and capricious, and that HHS did not provide the necessary comment period before approving the waiver proposal. It’s noteworthy that law professor Nicholas Bagley pointed out in 2019 that Tennessee’s proposal was likely not legal under the existing rules for Medicaid and the constraints of what can and can’t be changed with 1115 waivers.

In August 2021, the Biden administration re-opened a public comment period on some of the terms and conditions of the TennCare III waiver, and the McCutchen v. Becerra case was held in abeyance. The Biden administration indicated at the time that they were not changing or rescinding approval for the TennCare III demonstration, and were still considering how to proceed.

In mid-2022, however, the Biden administration notified Tennessee officials that they wanted the state to make some significant changes to the TennCare III demonstration proposals, including a return to a traditional per member per month cap, instead of the aggregate funding cap that the state had been using under the terms of the approval granted by the Trump administration. Tennessee adjusted its proposal soon thereafter to address the concerns that CMS had,16 and the amendments were approved by CMS in 2023.17 Notably, Tennessee had to return to a per-member-per-month methodology for assessing budget neutrality, instead of the aggregate (block grant) funding methodology that had previously been approved.18

History of Tennessee’s Medicaid block grant proposal

In May 2019, Tennessee Governor Bill Lee signed H.B.1280 into law. The legislation directed the state to seek federal permission to convert the state’s federal Medicaid matching funds into a block grant, indexed for inflation and population growth. The Trump administration had expressed willingness to consider such proposals, but Tennessee was the first state in the nation to enact legislation to get the ball rolling on it (and in November 2019, the White House Office of Management and Budget removed the administration’s guidance on block grant waivers).

In September 2019, Tennessee officials published the state’s block grant proposal (along with a summary and FAQ page), opening up a 30-day public comment period that ran through mid-October. During the comment period, advocates expressed concerns that Tennessee might use the waiver authority to reduce benefits for the state’s most vulnerable residents (Tennessee has not expanded Medicaid, so enrollees are all low-income and also either pregnant, elderly, disabled, children, or very low-income parents of minor children).

But the final version of the proposal, which was submitted to the Trump administration for review in November 2019,19 was modified in part to clarify that the state wouldn’t use its waiver authority to make benefit reductions, and that any benefit changes would be “additive in nature.”

So the revised proposal stated that Tennessee would be able to add benefits to the TennCare program without seeking additional CMS authority, but cannot use the block grant waiver authority to reduce the existing benefits package. The approval that CMS granted in January 2021 states that “Any coverage or benefit changes to existing populations covered are limited to those that are additive in nature, and the state is not authorized to make reductions to its current approved coverage or benefits package without approval of an amendment.“

Even so, a group of 21 prominent patient advocacy groups expressed strong opposition to Tennessee’s block grant waiver, noting that “It is irresponsible to approve this waiver during this public health crisis, and especially to do so for an unprecedented 10-year period. This waiver agreement, if implemented, will limit Tennessee’s flexibility in responding to recessions, pandemics, new treatments and natural disasters – and as a consequence moves in the opposite direction of the lessons learned from 2020.”

Tennessee’s proposal included a provision that would allow the state to share in any savings that the program generates, and was clear in noting that the state was proposing a modified block grant approach that would boost federal funding if enrollment in the program were to increase (as opposed to a traditional block grant model, which could result in a funding shortage for a state in the event of a recession or other incident that causes a sharp increase in the number of people eligible for Medicaid).20

Tennessee expected the block grant approach to result in “significant additional federal funding,” and hoped to use the money to provide additional services, such as nutritional assistance, housing support, and dental care.

The state’s proposal called for calculating the block grant based on “core medical services and related expenditures” for Tennessee’s Medicaid population, although some costs — such as prescription drugs, payments to hospitals for uncompensated care, and costs for Medicare-Medicaid dual-eligible enrollees — will not be included.

The idea of switching to a block grant model for federal Medicaid funding is not new. In 2017, the American Health Care Act (which passed in the House) and the Graham-Cassidy bill (which was introduced in the Senate but did not pass) both called for a block grant approach, and Republican lawmakers have long advocated this change. But for now, federal Medicaid funding continues to be an open-ended commitment from the federal government, with states receiving varying matching percentages to fund their Medicaid programs (in Tennessee, for every dollar the state spends on Medicaid, the federal government sends them $1.87. So federal funding covers about two-thirds of the cost of Tennessee’s Medicaid program).

Tennessee sought CMS approval for a Medicaid work requirement, despite rejecting Medicaid expansion

Tennessee is also one of several states with Medicaid work requirement proposals that are currently pending CMS approval.17 Tennessee’s 1115 waiver proposal for a work requirement was submitted in December 2018, under the terms of H.B.1551, which was signed by Governor Bill Haslam in May 2018.

In the waiver proposal that was submitted to CMS, the state notes that they received “a number of comments in opposition” to the work requirement proposal, but pointed out that state law (H.B.1551) requires the state to seek federal permission to implement a Medicaid work requirement (regardless of public opinion or comments). The work requirement was still pending federal approval more than six years after it was submitted.

The first Trump administration approved Medicaid work requirement waivers for several states. But a federal judge blocked implementation of the work requirements in some states, and the others were paused either in response to pending lawsuits or in response to the COVID pandemic. The Biden administration ultimately rescinded all approved work requirement proposals in 2021, and did not approve any that were still pending, including Tennessee’s. It’s unclear how pending work requirement proposals might fare under the second Trump administration.

Under the proposed waiver, Tennessee Medicaid enrollees subject to the work requirement would have had to work or participate in various community engagement activities for at least 20 hours per week to retain their Medicaid eligibility. The legislation also called for the state to seek federal permission to use TANF funding to implement the work requirement, which is noted in the state’s 1115 waiver proposal.

The terms of H.B.1551 call for a work requirement for TennCare enrollees who are “able-bodied working-age adult enrollees without dependent children under the age of six.” No other exemptions were specified in the text of the bill. But the proposal that was submitted to CMS in late 2018 includes various other exempt populations, including people age 65 and older (most other states with proposed or approved work requirements have opted to exempt people at a younger age, usually closer to 55), medically frail people, people who are mentally or physically unable to work (as certified by a medical professional), and people who are caring for a disabled individual over the age of six (in addition to one caretaker per household who is caring for any children under the age of six). A full list of exemptions is on page 3 of the work requirement proposal, and the state also notes that they would reserve the right to temporarily waive the work requirement in economically distressed counties.

Since Tennessee has not expanded Medicaid, the only population that would have been subject to the work requirement are parent/caretaker relatives — a population that now qualifies for Medicaid in Tennessee with income up to 105% of the federal poverty level (100% plus a 5% income disregard).4

According to the fiscal note for H.B.1551, there are about 300,000 TennCare enrollees in the parent and caretaker relatives eligibility category at any given time. Roughly half of them already meet, or are exempt from, the existing TANF/SNAP work requirements in Tennessee, so they would automatically have been deemed compliant with a Medicaid work requirement.

Nearly 49,000 of the remaining 150,000 enrollees are assumed to be the primary caregiver for a child under the age of six, and would thus be exempt from the work requirement. According to the fiscal note, additional exemptions, for people who are elderly, disabled, or in drug addiction treatment, bring the estimated number of people who would have been subject to the work requirement down to 86,439. Assumptions about exemptions are in the accompanying fiscal note.

(Note that the income limit for parent/caretaker TennCare enrollees was lower when that fiscal note was written; it was expanded to 105% FPL in mid-2024, increasing from 89% FPL.)

The fiscal note includes an estimate (based on KFF data) that 57% of the people subject to the work requirement were already working, leaving roughly 37,000 people who were not currently working, but who would be subject to the work requirement if it were to be enacted. The state expected that about 10% of those people would lose their Medicaid coverage due to failure to comply with the work requirement.

In a scathing report on the proposed waiver, however, Georgetown University’s Health Policy Institute notes that coverage losses could have ended up being far higher than the state estimated, citing the extensive coverage losses in Arkansas after a work requirement was implemented there.

It’s noteworthy that Arkansas did expand Medicaid, and thus allows able-bodied adults to be covered by the program even if they don’t have children (and the Arkansas work requirement included an exemption for parents with children under the age of 18, while Tennessee’s proposal only exempts one parent per household if they are taking care of a child under age six). In Tennessee, the only able-bodied, non-elderly adults enrolled in Medicaid are those who have dependent children and income that doesn’t exceed 105% of the poverty level (previously 89%), since the state has steadfastly rejected federal funding to expand its Medicaid program to cover more low-income adults.

The state proposed a monthly reporting requirement for members subject to the work requirement, with compliance checked once every six months. Those who hadn’t complied with the work requirement (and successfully reported their compliance) for at least four out of the six months would have lost access to TennCare until they demonstrated one month of compliance.

GOP lawmakers wanted to use TANF money to impose work requirement

H.B.1551 was amended by the House in March 2018, adding a section to the bill to require the state to also seek federal approval to use TANF (Temporary Assistance for Needy Families) funding or other federal funding to implement the work requirement. The state initially estimated that implementing the work requirement would cost more than $18 million per year in state funds, and Republican lawmakers wanted to use TANF money — designated to provide assistance to very low-income families — to cover the cost of imposing a work requirement that was designed to strip health coverage away from several thousand impoverished Tennessee residents.

Lawmakers noted in 2018 that TANF had $400 million in reserves in Tennessee, but one analysis clarified that the surplus was due to the paltry level of support that TANF provides in Tennessee: a maximum of $185/month in benefits for a family of three.

Proponents of the work requirement and the proposed TANF funding note that one of TANF’s stated goals is to get people into the workforce and encourage self-sufficiency. But stripping low-income parents of their health insurance is not likely to prove beneficial in the quest to help people get back on their feet. And the “supports” that the state has proposed include providing Medicaid enrollees with “access to information and services designed to prepare and support persons in obtaining and maintaining employment.” And people who need to complete secondary education, “will be connected to adult education opportunities sponsored by the Tennessee Department of Labor & Workforce Development.” More robust supports, including state-sponsored childcare, transportation, Internet access, etc. are not included in the proposed waiver.

H.B.1551 passed in the Tennessee House in March, on a 72-23 party-line vote. The text of the amended legislation that passed in the House clarifies that if the federal government does not approve the use of TANF funding (or other federal funding) to implement the work requirement, the state won’t move forward with seeking a waiver to impose a Medicaid work requirement.

House Democrats tried in vain to add several other amendments to the bill, including:

- An amendment to expand Medicaid and apply the work requirement to the expansion population.

- Amendments to exempt people going through substance abuse treatment, or who have a history of addiction or mental illness, from the work requirement

- An amendment to ensure that if parents of minor children were subjected to the work requirement, the state would seek to use TANF funds to pay senior citizens to provide childcare while the parents were working.

- An amendment that would require the state to seek approval to use TANF funding to provide jobs, paying at least $15/hour, to people subject to the work requirement.

- An amendment to exempt parents from the work requirement if they have children under the age of 12 (the bill calls for exempting parents if they have children under the age of 6).

An identical bill, S.B.1728, was introduced in the Senate in January 2018, but the Senate opted to substitute the amended version of H.B.1551 (with the requirement that the state must obtain TANF funding or other federal funding to implement the work requirement), voting on it in mid-April, and passing it overwhelmingly (23-2). In the Senate, several amendments were also rejected, including:

- An amendment to add Medicaid expansion to the legislation.

- An amendment to create an exemption from the work requirement for people experiencing domestic violence or acting as caregivers for other people, as well as an amendment to exempt people with bleeding disorders.

- An amendment that would call for the work requirement program to end after one year if the state’s costs associated with implementing the work requirement exceeded the state’s savings from the work requirement.

Although the Senate passed the measure in April, Tennessee officials had already posted a job opening for a “Policy Analyst to implement a new Medicaid work requirements program,” before the bill was even scheduled for a vote in the Senate. Critics of the proposed work requirement have denounced the state’s decision to post the job opening before the bill has been voted on in the Senate. But Tennessee’s Medicaid program defended the job listing, noting that if the bill did not pass, the state simply wouldn’t fill the position.

Former Governor Haslam pursued modified Medicaid expansion

In March 2013, Tennessee’s then-Governor, Bill Haslam unveiled his “Tennessee Plan” for Medicaid expansion. His proposal involved using federal Medicaid funding to purchase private coverage for up to 175,000 to 200,000 low-income Tennessee residents (Arkansas uses a similar approach). It also called for copays for some enrollees, payment systems for providers that are based on outcomes rather than fee-for-service, and a clause that requires future renewal of Medicaid expansion to be approved by the legislature.

In November 2014, Haslam announced that his negotiations with the federal government were ongoing, and this was still the case in December, although Haslam stated he had “verbal” approval from the federal government for his plan. In January 2015, Governor Haslam called for a special session of the Tennessee legislature to address his Insure Tennessee plan.

But Senate committees shut it down

But the following month, the Senate Health and Welfare Committee voted 7-4 against Haslam’s Medicaid expansion proposal, blocking it from going any further in the legislative process during the 2015 session. Although representatives from the Tennessee Hospital Association, the Tennessee Medical Association, and the Tennessee Business Roundtable all provided support for the Medicaid expansion proposal, it was not enough to sway the conservative lawmakers who were concerned about the long-term costs to the state or the difficulty the state would face if it were to try to repeal Medicaid expansion a few years down the road.

The Insure Tennessee legislation was considered again by another Senate Committee in March 2015, but it too was ultimately rejected. That version called for the state to wait until the Supreme Court ruled on King v. Burwell before proceeding with Medicaid expansion (in June 2015, the Court ruled that premium subsidies are legal in every state, thus preventing destabilization in the individual insurance market in Tennessee). It also called for a six-month waiting period before Medicaid coverage could be reinstated if it were terminated because an enrollee didn’t pay premiums, and it required the state to obtain a letter from HHS stating that Medicaid expansion could be terminated at any time, at the state’s discretion.

A variety of bills, including SJR0103, HB1324, and HB1271, were introduced to expand Medicaid during the 2015 legislative session, but none of them advanced to a full vote.

Haslam had considered calling lawmakers back for another special session to address Medicaid expansion again, but said in April 2015 that he wouldn’t do so until it appeared that legislators had softened to the idea of Medicaid expansion, or were at least beginning to agree on modifications to the current proposal. Tennessee relies heavily on uncompensated care funding from the federal government, and by the fall of 2015, it was clear that the funding was in peril. Expanding Medicaid would eliminate much of the need for ongoing uncompensated care funding.

3-Star Healthy Task Force

In April 2016, Tennessee House Speaker Beth Harwell detailed the creation of a legislative task force to address access to healthcare in the state. Democrats roundly criticized the task force, calling it a joke and noting that there were no Democrats on the task force. Governor Haslam stopped short of saying that the 3-Star Healthy Project’s formation indicated that Insure Tennessee was dead, but acknowledged that Insure Tennessee hasn’t been able to get traction with the legislature, and noted that the plan that would work best would be one that could garner support from Tennessee lawmakers.

The “3-Star Healthy Project” task force began meeting to come up with proposals that could be sent to the federal government, and by September, they had a TennCare expansion proposal ready to send to CMS, although by early November, the schedule was that it would be submitted to CMS by the end of 2016. While it was better than nothing, it was a far cry from Haslam’s Insure Tennessee proposal.

In its initial phase, the pilot program was slated to expand TennCare eligibility only to people with mental health and substance abuse disorders, and to veterans. These groups would have been eligible for TennCare with income up to 138% of the poverty level, under the terms of the expansion pilot.

But when Donald Trump won the presidential election in November 2016, the TennCare expansion proposal was put on hold while the state waited to see what would happen with healthcare reform at the federal level under the new Administration. Ultimately, the ACA was not repealed (as some had expected after Trump’s victory), but the Trump administration opened the door for Medicaid waivers with provisions that the Obama administration never allowed, including work requirements and block grants.

Republican lawmakers introduced legislation (S.B.118 and H.B.69) in 2017, based in part on the work done by the 3-Star Healthy Task Force, calling for the state to propose a federal waiver to expand Medicaid using a block grant. Both bills were tabled in 2017, but reconsidered in 2018. Ultimately, H.B.69 was tabled again in 2018, and S.B.118 failed in committee. Ultimately, the state has enacted legislation that simply calls for the state to seek a transition to a block grant, but without expanding Medicaid.

Medicaid expansion via Insure Tennessee was also introduced again in the Tennessee House in 2018, but did not advance. A bipartisan proposal to allow people age 55 or older to purchase TennCare (i.e., a Medicaid buy-in program) also did not advance.

Tennessee Medicaid enrollment numbers

A total of 1,628,196 people had coverage through Tennessee’s Medicaid and CHIP programs as of July 2016. That was a 31% increase since the end of 2013, despite the fact that the state had not expanded Medicaid. People who were already eligible for Medicaid under the existing guidelines were newly enrolled thanks to the outreach and enrollment efforts under the ACA.

Enrollment in Tennessee’s Medicaid/CHIP coverage fell sharply after 2016 amid the state’s efforts to purge children from the coverage rolls (due in some cases to paperwork falling through the cracks, and in others to families’ eligibility status changing). In February 2019, total enrollment stood at just over 1.3 million people.

But as of September 2024, Tennessee Medicaid and CHIP enrollment stood at about 1.44 million.21 This was a 16% increase over enrollment in 201322 Enrollment had been much higher in early 2023, but had dropped significantly during the post-pandemic “unwinding” period when eligibility was rechecked for all enrollees after a three-year pause.

Tennessee Medicaid history

Tennessee was among the last states to implement Medicaid, with their program taking effect in January 1969, three years after Medicaid was enacted.

TennCare was created in 1994 under a federal waiver that allowed for some deviations from the standard Medicaid program. TennCare was the first Medicaid program to utilize private sector managed care for all of its members. Initially, TennCare was available at no cost for Medicaid-eligible residents, and also on a sliding-fee scale (premiums were subsidized) for Tennessee residents who were not able to obtain other private insurance, particularly those who couldn’t get other coverage because of pre-existing conditions.

By 1995, amid soaring enrollment, TennCare stopped accepting applications from non-Medicaid eligible adults unless they were unable to get other coverage because of pre-existing conditions. And later the “uninsurable” population eligible for TennCare was reduced by implementing income caps for their eligibility.

TennCare’s financial viability continued to be in question, and in 2005 the state removed about 190,000 beneficiaries from the program, implemented benefit reductions, and put caps on the number of prescriptions a TennCare member could get.

Eventually, Tennessee created CoverTN and AccessTN to provide coverage for certain small business groups, the self-employed, and people who were otherwise uninsurable. Following the reforms and the shift to only insuring the Medicaid-eligible population through TennCare, the program’s budget seemed to be getting back on track by the late 00’s.

When the ACA was created, it was intended that Medicaid expansion would be nationwide, so subsidies in the exchange were not designed to apply to people living below the poverty level, since they were expected to have access to Medicaid. But in 2012, the Supreme Court ruled that states could opt out of Medicaid expansion, and Tennessee is one of 10 states that have not yet expanded their programs as of 2025.

Because the state has rejected Medicaid expansion under the ACA, Tennessee missed out on $22.5 billion in federal funding from 2013 to 2022. In addition, Tennessee residents have paid $7.8 billion in federal taxes that have been used to fund Medicaid expansion in states that are expanding coverage — while getting no Medicaid expansion funds for their own state.

Recent legislation related to Medicaid in Tennessee

Louise Norris is an individual health insurance broker who has been writing about health insurance and health reform since 2006. She has written dozens of opinions and educational pieces about the Affordable Care Act for healthinsurance.org.

Looking for more information about other options in your state?

Need help navigating health insurance options in Tennessee?

Explore more resources for options in Tennessee including ACA coverage, short-term health insurance, dental insurance and Medicare.

Speak to a sales agent at a licensed insurance agency.

Footnotes

- Medicaid, Children’s Health Insurance Program, & Basic Health Program Eligibility Levels. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. December 2023. ⤶

- The 5% Federal Poverty Limit Disregard for MAGI. Division of TennCare. Accessed February 2024 ⤶

- ”Medicaid Income Eligibility Limits for Adults as a Percent of the Federal Poverty Level” KFF.org. May 1, 2024 ⤶

- ”Waiver approval letter to TennCare” Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. May 21, 2024 ⤶ ⤶ ⤶ ⤶

- How Many Uninsured Are in the Coverage Gap and How Many Could be Eligible if All States Adopted the Medicaid Expansion? KFF. Feb. 26, 2024 ⤶

- ”Study: Medicaid expansion could cover 150,000 more Tennesseans and save the state millions of dollars” 90.3 WPLN News. Nov. 3, 2023 ⤶ ⤶

- ”Tennessee HB1101” and “Tennessee SB851” BillTrack50. Accessed Feb. 10, 2025 ⤶

- Tennessee HB2599, Tennessee HB2330, Tennessee SB2553, Tennessee SB2450, Tennessee SB2733. BillTrack50. Accessed Oct. 15, 2024 ⤶

- Tennessee SB1161, Tennessee HB1402, and Tennessee HB890. BillTrack50. Introduced 2023 ⤶

- Republican rep wants to return Medicaid expansion authority to governor. Tennessee Lookout. December 2023. ⤶

- ”October 2024 Medicaid & CHIP Enrollment Data Highlight” Medicaid.gov, Accessed Jan. 7, 2025 ⤶

- ”Medicaid Enrollment and Unwinding Tracker” KFF.org, Dec. 4, 2024 ⤶ ⤶

- Expand Medicaid in Tennessee. Tennessee Justice Center. Accessed February 9, 2024. ⤶

- ”September 2024 Medicaid & CHIP Enrollment Data Highlight” Medicaid.gov, Accessed Jan. 7, 2025 ⤶

- HealthCare.gov Marketplace Medicaid Unwinding Report. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Data through April 2024 ⤶

- TennCare III Demonstration Amendment 4. Letter from TennCare to CMS. August 30, 2022. ⤶

- TennCare III (subsumes TennCare II). Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Accessed February 9, 2024. ⤶ ⤶

- Demonstration Approval — Amendment 4. Letter from CMS to TennCare. August 4, 2023 ⤶

- ”TennCare II Demonstration, Amendment 42, Modified Block Grant and Accountability” Division of TennCare. Nov. 20, 2019 ⤶

- ”Why it Matters: Tennessee’s Medicaid Block Grant Waiver Proposal” KFF.org. Dec. 9, 2019 ⤶

- September 2023 Medicaid & CHIP Enrollment Data Highlight, Medicaid.gov, Accessed Jan. 7, 2025 ⤶

- Total Monthly Medicaid & CHIP Enrollment and Pre-ACA Enrollment. KFF. Accessed Jan 7. 2025 ⤶