During the New Hampshire Debate the other evening, in her response to the very first question of the evening, when asked why she feels that Bernie Sanders is making promises he can’t possibly keep, Hillary Clinton stated:

Senator Sanders and I share some very big progressive goals. I've been fighting for universal healthcare for many years, and we're now on the path to achieving it. I don't want us to start over again. I think that would be a great mistake, to once again plunge our country into a contentious debate about whether we should have and what kind of system we should have for healthcare.

I want to build on the progress we've made; get from 90 percent coverage to 100 percent coverage. And I don't want to rip away the security that people finally have; 18 million people now have healthcare; pre-existing conditions are no longer a bar. So we have a difference.

It's that "from 90 percent to 100 percent" that I want to talk about here.

The Presidential health reform debate shifts left

Over the past few weeks, the battle over healthcare coverage in America has heated up again ... but this time it's all on the Democratic side. Bernie Sanders admits that the Affordable Care Act has improved things to some degree, but not nearly enough, and is pushing hard for his single payer healthcare plan as the panacea to resolve our healthcare woes. Hillary Clinton, meanwhile, prefers an incremental approach, building gradually on the Affordable Care Act to achieve universal coverage.

Emotions are high and tempers are flaring, to put it mildly, over an issue which, until this development, was really only being duked out on the Republican side of the aisle, where the only thing they can agree on is that they want to get rid of the ACA entirely. I foolishly stepped into the debate a couple of weeks ago with my own thoughts, and set off a bit of a firestorm in the process. My main take is that Sanders is promising way too much, way too quickly … but Clinton gives the impression of not pushing to do enough, ever.

Defining universal coverage goals

As I see it, there are five main goals here: Coverage which is Universal, Affordable, Comprehensive, Portable and Simple to manage.

Part of the problem is that many people (including myself, until recently) are confused about what some of these terms actually mean.

- Single Payer is simply a system in which taxes are paid to the government, which it in turn uses to pay the doctors and hospitals for providing medical treatment. That's it. Single Payer by itself is simple and portable ... but that doesn't guarantee that it's comprehensive, universal or affordable.

- For instance, Medicare is a single-payer system, and is generally affordable ... but only covers about 16 percent of the country (not universal), and most people enrolled in it require supplemental Medigap coverage as well. (It's not comprehensive.)

- Medicaid is also simple and obviously affordable for those enrolled, and is pretty comprehensive ... but it's not universal either, and is absolutely NOT portable. (Many doctors refuse to accept Medicaid patients because the reimbursement rate is so low.)

- On the flip side, the ACA made sure that private healthcare plan coverage from, say, Aetna or Cigna has to be comprehensive, and the federal tax credits help make it affordable for those at lower or mid-range income levels ... but it may not be portable (i.e, narrow networks), and isn't universal. (The ACA doesn't cover undocumented immigrants at all; 19 Republican-controlled states to refuse to expand Medicaid; and for millions of others, the policies are still too expensive even with the current financial assistance allowed.)

Health insurance and coverage is insanely complicated. Whole books have been written about how to improve (or replace) the system; perhaps I'll write one myself. In the meantime, however, here are my thoughts about how I think we should proceed with the first of these goals (UNIVERSAL coverage) ... in simplified form.

Again, for the moment I’m setting aside the other goals, although affordability and comprehensiveness do come into play in some places.

America's mish-mash of health coverage

First, it's important to point out that our current healthcare system is a mish-mash mostly consisting of the following (and yes, I'm sure I'm still missing a few):

- Medicare (public)

- Medigap (private)

- Medicare Advantage (quasi-private)

- Traditional Medicaid (public)

- ACA Medicaid expansion (public)

- S-CHIP (public)

- ACA Medicaid "Private Option" in Arkansas/etc. (private plans, public financing)

- VA/TriCare (public)

- Large-group employer-sponsored insurance or ESI (private)

- Small-group ESI (private)

- ACA exchange QHPs (private plans, partial public financing)

- ACA Basic Health Plans (BHP) (private plans, public financing)

- ACA exchange SHOP policies (private plans, partial public financing)

- Off-exchange QHPs (private)

- Off-exchange non-QHPs (private)

- Short-term coverage (private)

Wow. That's quite a list. Notice that the ACA has helped expand coverage to around 18 million more people, and has made many of the existing categories more comprehensive. (All policies are now required to have certain minimal coverage, etc.) It still leaves around 29 to 32 million people uninsured completely.

My plan to cover the rest ... or most of the rest

So, setting aside the other four goals for the moment, how would I cover the remaining 9 to 10 percent of the population within the existing structure?

In an earlier post, I suggested expanding Medicare very gradually, lowering the age one year at a time to allow the rest of the economy and the healthcare system time to absorb around 3 million more people per year. I still stand by that as one option, but I also wanted to see how I could get to full coverage (or at least near-full) without touching the Medicare system at all.

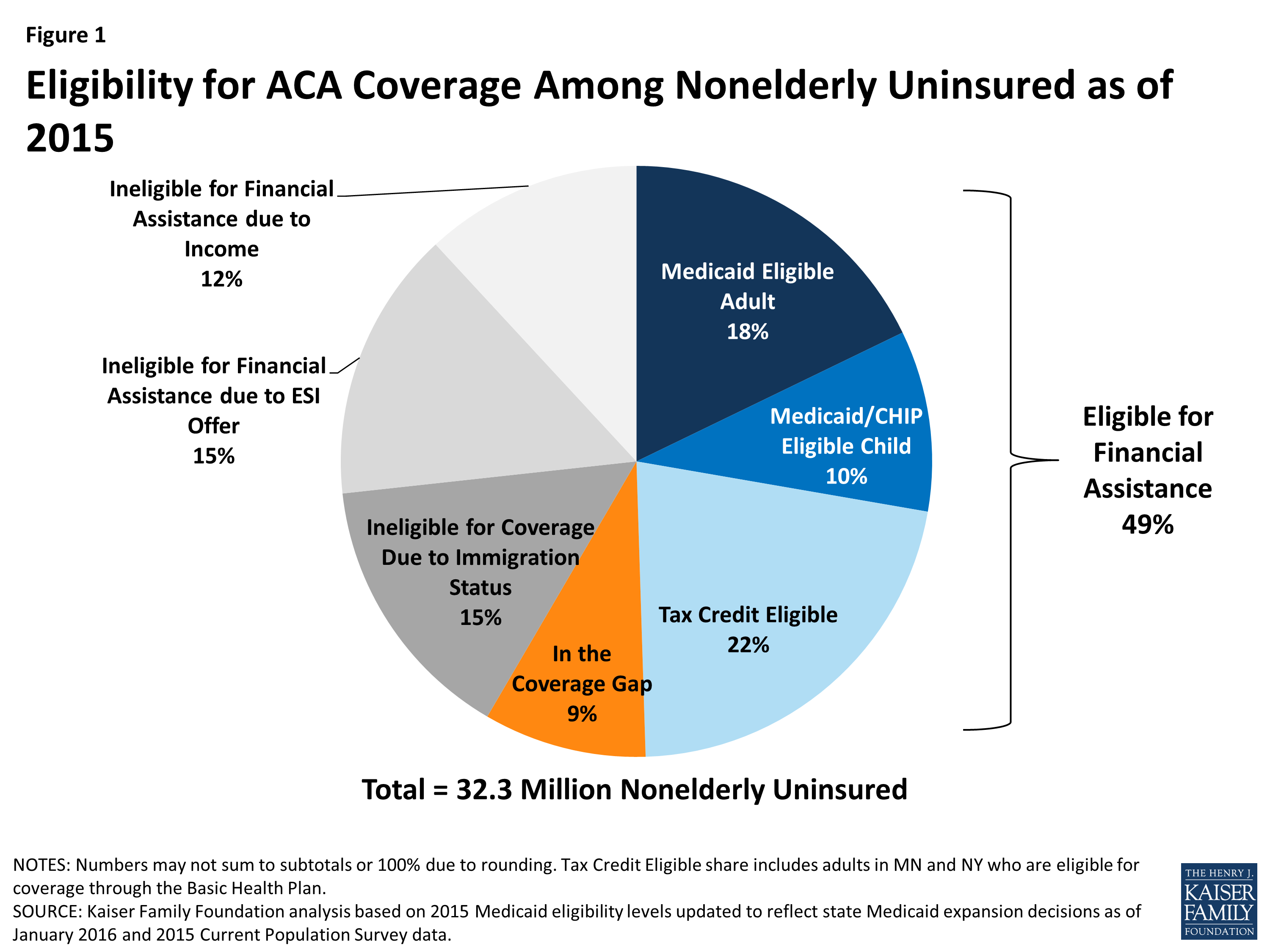

First, let's look at who these folks are. Estimates vary depending on which source you use and what criteria you're basing your definition on, but for me, the Gold Standard is probably the Kaiser Family Foundation's Estimate of Eligibility for ACA Coverage among the Uninsured. This was most recently updated in January 2016, although the data itself comes from various points throughout 2015; as a result, it doesn't take the just-ended 2016 Open Enrollment Period into account, although Louisiana Governor Jon Bel Edwards's recent expansion of Medicaid in his state has been included.

Here's KFF's best estimate of the total uninsured population in the U.S. at the moment:

99 is the new 100.

As you can see, they peg total uninsured at around 32.3 million people. Also note that this is for the non-elderly (under 65 years old). The assumption is that everyone over 65 is on Medicare, but the reality is that even with Medicare, 1.7 percent of the over-65 population (around 700,000 people) was still uninsured as of 2012.

That's important for two reasons: First, it means that the total above is actually around 33.0 million. More significantly, it means that even with "universal" coverage, you'll never get to 100 percent.

Who are those 700,000 people who aren't covered in any way? No Medicare, no Medicaid, no private coverage? I'm guessing most are undocumented immigrants; regardless, we have to accept that even "100 percent" coverage will only be around 99 percent at best no matter what.

Nationally, at least 3 million people will always be uncovered no matter how you slice it. And yes, I'm pretty sure that would be true even with Bernie Sanders's theoretical Single Payer system. With that in mind, we're really talking about attempting to cover roughly 30 million people, not 33 million.

Using the KFF proportions above, that gives us:

- 6.6 million eligible for ACA tax credits

- 5.4 million eligible for Medicaid

- 3.0 million eligible for S-CHIP

- 2.7 million caught in the Medicaid Gap (19 GOP states only; Louisiana's 300K already subtracted)

- 4.5 million undocumented immigrants

- 4.5 million ineligible for ACA tax credits due to having a standing ESI offer

- 3.6 million ineligible for ACA tax credits due to their income being above 400% FPL

How much did OEP 3 move the needle?

Next, what impact has the 2016 open enrollment period had? We won't know that for awhile, but there was a net increase of about 1.0 million ACA exchange enrollees this year, plus around 400,000 BHP enrollees in New York. Medicaid and Medicare enrollments also quietly increase every month, and the odds are that at least a half million or so more people signed up for off-exchange policies (even at full price) to avoid the individual mandate penalty.

Some of these people were already covered one way or another, but I'd be willing to bet that when the March uninsured reports come out, they'll reflect a net reduction of around 1.5 million more people or so, leaving it at something like:

- 6.0 million eligible for ACA tax credits

- 5.0 million eligible for Medicaid

- 3.0 million eligible for S-CHIP

- 2.7 million caught in the Medicaid Gap

- 4.5 million undocumented immigrants

- 4.5 million ineligible for ACA tax credits due to having a standing ESI offer

- 3.2 million ineligible for ACA tax credits due to their income being above 400% FPL

So let's see where we can make improvement:

1. The Medicaid Gap: 2.7 million

The problem with the 2.7 million in the Medicaid Gap is purely a political issue (well, it's financial as well, but mainly political). Right now, here's the Medicaid situation in those 19 states: Each one has up to eight different income threshold eligibility levels for different groups of people.

In Alabama, for instance, children and pregnant women are eligible up to 141% FPL ... but non-pregnant parents are only eligible up to 13% FPL (which is a whopping $40 per week for a single parent of one child). Adults who don't have kids under 18 aren't eligible at all.

In Georgia, meanwhile, pregnant women are covered up to 220%, but their newborn child only up to 205%. Once the baby turns a year old, they're only covered up to 149% ... but when they turn 6, it drops to 133% FPL. Meanwhile, the kids' parents are only eligible up to 30%. Confusing to say the least. Adults w/out kids are still screwed.

The funding of Medicaid is equally confusing: The federal government pays anywhere between 51 and 76% of Medicaid costs depending on the state; the state pays the rest. I have no idea what the criteria is for this percentage going up or down.

The idea behind ACA Medicaid expansion was supposed to be this: Expand Medicaid to cover everyone eligible up to 138% FPL regardless of their age, parental status or whether they have kids at all. In return, the feds would pay for 100 percent of the costs for the expansion-eligible enrollees only for the first three years, then gradually drop that down to 90 percent, where it would stay put.

Half the states took the deal; a handful more grudgingly came around, and 19 are still refusing to take the best bargain they'll ever see. Furthermore, we're now into the third year of the program, so that 100 percent funding offer is starting to drift downward a bit.

In response, President Obama is offering to sweeten the deal: He's proposed having the three-year 100-percent funding offer start at whatever point the state expands the program, instead of 2014-2016 only.

My proposed fix:

This is a good idea, and perhaps it'll bring around a state or two, but I'd make a more comprehensive offer to every state (and yes, this would have to apply to the 31 states which have already expanded Medicaid as well, to be fair):

- The states would agree to cover every legal resident up to 138% of the federal poverty line (ie, the current offer) and

- The states would agree to set medicaid coverage for every enrollee to the same, higher level of coverage, plus

- The handful of states which have insisted on "more conservative" Medicaid waivers with annoying provisions (Alabama, Indiana, etc) would agree to switch to regular Medicaid.

- In return, the federal government would agree to permanently pay 90% of the cost of ALL Medicaid enrollees, regardless of whether they're covered under pre- or post-ACA provsions.

This would simplify and improve things dramatically in a number of ways:

- It should be jumped on by even GOP governors/state legislators, since it would let them brag about saving the state hundreds of millions of dollars while simultaneously increasing the number of poor people covered.

- It would make sure that states didn't try to increase the number covered at the expense of the quality of that coverage (ie, playing games by pitting one subpopulation against another).

- It would simplify/eliminate some of the complicated jumping around of income thresholds for different age groups/etc, as well as making it easier for states (and the federal government) to make budget projections. (Instead of having the ratio jump around from state to state, they'd just know: Feds 90%, State 10%.)

Obviously the biggest issue here is that aside from increasing total Medicaid spending by about $16 billion (assuming $5,800 per enrollee x 2.7 million people), it would also shift around 30 percent of total Medicaid spending (roughly $475 billion per year) from the states to the federal government. This would save the states around $140 billion collectively, but would increase the federal budget by a similar amount (plus, of course, another $14 billion or so for their share of the additional 2.7 million enrollees).

Would the states go for this? Would Congress? I have no idea ... but it'd be a hell of a lot more likely to go through than a wholesale Single Payer overhaul. If it did go through and was agreed to by all 19 states, that should cut the uncovered rate down by perhaps an additional 2.5 million.

Result: 2.5 million more insured

2. "Regular" Medicaid/S-CHIP eligible: 8.0 million

The most striking sections of the KFF's chart above have little to do with the ACA. According to their surveys, 5 million adults and 3 million children are already eligible for Medicaid or the S-CHIP program (regardless of whether it's via ACA expansion or not) ... but still haven't signed up yet.

The reasons for this vary. Some people have no idea what Medicaid is, or have no idea that they qualify for it. Some people may not understand the paperwork or process involved. Some may be reluctant to enroll due to the social stigma which Medicaid has had for years.

The good news is that these numbers are lower than they were a few years ago. Medicaid enrollment has gone up over 14 million people since October 2013 ... but only about 10 million of that is due to ACA expansion. The other 4 million are mostly people who had already been eligible for the program, but who have only signed up for it since the ACA expansion and exchanges went into effect.

The law included funding and provisions which helped streamline the Medicaid enrollment process, including things like helping states like Oregon and West Virginia cross-index databases of food stamp recipients to automatically enroll them, for instance. In addition, increasing the income threshold likely had some positive effect on reducing the social stigma of being on Medicaid in some areas. However, that's still only about 1/3 of the people who qualify; 8 million or so others still don't seem to have gotten the message (or are choosing to ignore it).

Louise Radnofsky of the Wall St. Journal actually wrote a feature article about exactly this crowd last week; her numbers don't match up with KFF. (She has it down as 6 million, although that might not include the S-CHIP group), but the article itself notes both the successes since the ACA was passed as well as the challenges it still faces:

To get at these holdouts, the administration is enlarging a national campaign that had been aimed at enrolling low-income children to include their parents, too. Federal officials also say they will offer $32 million in grants in the spring for outreach and enrollment work, adding to about $126 million given out in the past six years.

But it is uphill work – and government forecasters including the Congressional Budget Office don't see the number of people who are eligible for Medicaid but unenrolled budging significantly over time.

... The biggest hurdle for those who want to sign up the Medicaid holdouts might be that not a lot is known about their motivations for staying out of the system.

Mike Perry, a pollster who has studied people's experiences with Medicaid, has found one reason some don't enroll is that they see their hardships to be temporary and liable to improve soon.

That presents experts an additional conundrum. To avoid having people like Ms. Collier drop out of Medicaid, some states have experimented with making them eligible for long stretches of time, rather than continuously investing in reassessing their status. Others worry that the programs will be undermined in the eyes of taxpayers – and enrollees – if they don't continually re-evaluate eligibility.

Both the $32 million grant program as well as the "long-term eligibility" idea make total sense to me. I assume that Medicaid enrollees are currently evaluated monthly, which means a ton of paperwork and red tape.

The idea is to prevent those whose financial situation improves from continuing to "sponge off the system" afterwards, but I have to imagine that the administrative overhead is cancelling out a lot of the savings from checking their status 12 times per year. Dropping from monthly to annually (or at least every 6 months?) would reduce the amount of overhead while also encouraging more people to sign up, as noted in the WSJ article.

Here's the thing: Medicare is primarily age-based: Once you turn 65, you qualify for life, period. Medicaid is income-based, not age-based, and income is constantly jumping up and down. This is another way in which standardizing eligibility across the board and merging the systems for "regular" and "expanded" Medicaid would help: There would be fewer eligibility thresholds to worry about being above or below.

Possible fixes:

So, what else could be done to help? Well, I'd beef up the outreach/enrollment grants even more (a couple hundred million dollars, perhaps?) ... but the key really seems to be similar to the new automatic voter registration laws in Oregon and California.

Instead of requiring eligible individuals to actively enroll in Medicaid, how about having it done automatically when they file their taxes if it falls below the income threshold and they aren't otherwise covered? This wouldn't do anything for those who don't make enough to file a tax form at all, but it should take care of a substantial chunk of them.

Over at Balloon-Juice, Richard Mayhew has another great "automatic" idea, at least when it comes to covering children: expanding Childrens' Health Insurance Program (CHIP) to essentially cover every kid.

Oh, yeah, there's one more change I would make to help reduce confusion among both the uninsured and everyone else: Have the states stop using other names for the program.

Right now only 12 states actually call Medicaid "Medicaid." Every other state has their own weird, goofy name for it. I realize that this may reduce the stigma in some states, but it also confuses people when it comes to budget discussions. I guarantee you that there are millions of people on Medicaid who don't even know it ... which means that any time a state legislator talks about "cutting Medicaid funding," some of those same people are all for doing so without realizing that they're on the very program that they're rooting to be cut.

This may have been part of the problem in Kentucky's recent gubernatorial election, for instance: Kentucky has six different names for its Medicaid program, none of which actually has the word "Medicaid" in it (KYHealth Choices, WellCare, etc).

How much impact would all of these efforts have? There's around 74 million children under 18 in the U.S., of which KFF estimates around 6 percent were uninsured as of 2014, or around 4.4 million. Subtracting undocumented immigrants and overlap with other categories, Mayhew's "CHIP for All" idea would instantly cover around 3 million of them. Setting that aside, I could see an automatic enrollment process getting up to 2 million more adults into the system.

Result: Up to 3 million more kids and 2 million more adults covered

3. Undocumented immigrants: 4.5 million

There are actually around 11 million undocumented immigrants in the U.S., but according to KFF, only about 4.5 million of them are actually uninsured. The rest actually do have coverage from various sources, including: student health plans, employer-based health insurance, private health insurance, Medi-Cal coverage, community health centers, state-based health programs.

As for the 4.5 million who are still uncovered, what can I say? Either individual states or Congress itself would have to change their laws (or the ACA, or some separate law) to allow undocumented immigrants to legally enroll in either Medicaid, Medicare, and/or to receive tax credits via the ACA exchanges.

The odds of this happening nationally are roughly zilch, but California recently passed a state-level law allowing 170K undocumented children to enroll in Medicaid; this is something more likely to happen at the state level, though I wouldn't expect other big immigration states like Texas, Florida or Arizona to follow, like, ever.

Results: Perhaps 0.5 million more undocumented immigrants covered if a handful of states follow California's lead?

4. Ineligible for ACA tax credits due to having standing ESI offer: 4.5 million

OK, now we're off of the fully public side and into the private policy market.

For the "standing ESI offer" category, I'm actually going to turn to a writer who's generally been negative on the ACA, but who believes the problems with the law can be fixed. Here's what he has to say about the ACA's so-called "Skinny" Plan Loophole in Jed Graham's e-book, "ObamaCare is a Great Mess":

... The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act created a web of insurance safeguards that the law's crafters expected to make such skimpy coverage a thing of the past. But its protections have turned out to be no match for low-wage industries and their insurance industry allies seeking to minimize potentially steep penalties employers could face under ObamaCare.

The Obama administration appears to have been too sanguine about the prospects that the employer fines would simply nudge low-wage employers to offer their workers quality, affordable coverage. That is likely happening to some degree because there are advantages to providing health coverage: better worker morale, less employee turnover and superior customer service. Yet some low-wage employers with thin profit margins have reached a conclusion that the cost of providing reasonably comprehensive coverage is unrealistic.

For such businesses determined to minimize the cost of complying with ObamaCare, the employer mandate offers some pretty perverse incentives. The law's "skinny" plan loophole, first revealed by Christopher Weaver and Anna Wilde Matthews of The Wall Street Journal, allows companies to escape ObamaCare's most stringent penalty simply by offering the most bare-bones coverage imaginable.

Employers who offer no qualifying coverage of any kind are subject to a fine of $2,080 for each full-time worker (with an exemption for 30 workers). Yet avoiding this across-the-board fine turns out to be pretty easy. All it requires is meeting ObamaCare's lesser standard of offering minimum essential coverage, whose definition turns out to be flexible enough to apply to plans that exclude hospitalization, surgery and all non-generic drugs.

Graham goes into much more detail about the "skinny plan" loophole, but for my purposes, this is the crux of it:

Many of their low-wage workers might not be eligible to buy subsidized coverage through HealthCare.gov or their state exchange. If an employer offers comprehensive coverage that costs no more than 9.56% of a worker's pay in 2015, that coverage is deemed affordable and the worker isn't entitled to any exchange subsidies. In that case, a company might think it's doing workers a favor by offering a skinny plan as a way for them to buy coverage on the cheap and avoid paying an individual mandate penalty.

Undoubtedly, many low-wage workers would object to ObamaCare's affordability standard: For a $20,000-earner, a $ 1,900 insurance premium would be onerous, costing nearly twice as much as a subsidized silver exchange plan and about four times as much as bronze coverage. Here is the problem: If low-wage workers are offered employer coverage that qualifies as affordable – even if it isn't – then the only policy within their financial reach may be a skinny one.

Yup. That's a big part of the reason why these 4.5 million people haven't signed up yet: They aren't eligible for exchange subsidies because their employer has "offered" them a company policy which is "comprehensive" and allegedly "affordable." Since in many cases the company policy is neither of the above, these folks are left with two options: Either pay full price for an exchange (or off-exchange) policy … or continue to remain uncovered and eat the individual mandate penalty. The Silver lining here is that the mandate penalty exemption cut-off is 8.05 percent of their income, so many of this crowd at least won't have to pay the tax.

Possible fix?

The solution here is actually pretty simple, although, again, the odds of getting this through Congress is a bit on the slim side: Change the ACA to either a) lower the 9.56 percent threshold for exchange subsidy eligibility; b) get rid of the provision which allows employer plans to be too "skinny", or both. Personally, I tend to err on the side of lowering the threshold, since that also helps eliminate the "job lock" issue, in which people are tied into their current employer for the healthcare benefits rather than the salary/pay itself.

How effective would this prove to be? I figure this would push perhaps a third of the “ESI Offer” population was into action, for 1.5 million more sliced off the uninsured pile.

Result: 1.5 million more insured

5. Eligible for ACA tax credits (but haven't taken them yet): 6.0 million

6. Ineligible for ACA tax credits because income is too high: 3.2 million

Finally, we come to the heart of what I'm best known for: Tracking how many people sign up for ACA exchange-based policies, versus how many ... well ... could, but don't.

The main reason why people who could sign up for private policies via the exchanges don't do so is simple: Cost. Again, according to a KFF survey from last fall:

Cost still poses a major barrier to coverage for the uninsured. In 2014, 48% of uninsured adults said that the main reason they lacked coverage was because it was too expensive ... Few uninsured adults said they were uninsured because they do not need coverage, oppose the ACA, or would rather pay the penalty.

At least 3.2 million people who earn over 400% of the Federal Poverty Line (and could therefore easily afford at least a Bronze or Silver policy if they wanted to) choose not to do so, eating the $695 / 2.5% household income Mandate Tax instead.

Since 400% FPL is around $97,000 for a family of four, that means such families apparently would rather pay a $2,400 penalty than be covered at all, which strikes me as being insane, but what're you gonna do? I suspect that most people, especially at that income level, aren't willing to risk leaving their kids uncovered, though (unless they're really wealthy ... like, in the $1 million+ income range), so I'll assume this is mostly single adults or couples without any kids. For an individual that's $47,000 per year ($1,200 penalty); for a couple it's $64K ($1,600 penalty).

As for the 6.0 million between 100% and 400% FPL who do qualify for tax credits, the problem isn't so much at the low end, since those under 250% FPL (and especially those below 200% FPL) also receive Cost Sharing Reductions to mitigate high deductibles and co-pays. For those from 200%-400%, FPL, however, the costs of premiums and deductibles can really rack up, even with financial assistance.

Simple fix?

Once again, assuming the goal (for the moment) is only to ensure maximum coverage, there's yet another "simple" solution at hand: Modify the ACA to beef up APTC (advance premium tax credit) assistance (with more generous credits in the 200%-400% FPL range, and possibly even offering limited credits up to 500% FPL), while extending the CSR assistance up the ladder as well (perhaps to 400%).

I'd also give up on limiting CSR to Silver plans; I understand the reasoning, but it's only confusing the hell out of people who don't understand why a Bronze plan (which they assume will cost less) actually costs more than a Silver plan when deductibles are taken into account. Fellow healthinsurance.org blogger Andrew Sprung is a bit obsessive about the CSR conundrum, and offers this suggestion:

CSR could attach as easily to Bronze as to Silver, without increasing the subsidy level. The CSR subsidies are based on a plan's actuarial value (AV) – the percentage of the average user's yearly medical expenses that the plan is designed to pay. Without CSR, silver ACA plans have a mandated AV of 70%; bronze, 60%. Depending on income level, CSR raises the AV of a silver plan to 94%, 87%, or 73%. Why could the subsidy not be available with a bronze plan, boosting AV to 84%, 77% and 63%? Or, if the subsidy needs to be a ratio of the unsubsidized AV, CSR could boost bronze AVs to 81%, 75%, and 63%. Or whatever, to make the subsidy cost the Treasury the same amount at different metal levels.

Taking the Kaiser survey results at face value, a move like this would theoretically get at least half of those 6 million people off the fence, while also encouraging perhaps 1/3 of the over-400% crowd to go ahead and sign up. That's a further reduction in the uninsured of around 4 million people.

The Affordable Care Act also has another provision which can address the lower-income crowd: The Basic Health Plan (BHP) program which, until this year, was only being utilized by Minnesota (which already had a similar program in place). Around 77,000 Minnesotans below 200% FPL are enrolled in MinnesotaCare, which is a fantastic bargain for enrollees. New York just became the second state to implement BHP, and it’s been a huge success: 400,000 state residents signed up in the first year. While around half of them were “cannibalized” from official private QHPs, another 100K or more are newly covered. Andrew Sprung has more details on the tremendous possibilities of the BHP system … if additional states can be encouraged to take advantage of it.

What would it take to encourage them? Well, according to this article at NPR, it’s once again about cost to the states:

So why aren't more states putting a basic health program in place? Implementation makes more sense in some states than in others. New York and Minnesota, for example, were already providing Medicaid coverage to many people now eligible for the basic health plan. For those states, and a handful of others with more comprehensive Medicaid coverage, moving residents from Medicaid, where the state pays about 50 percent of the cost of coverage, to the basic health program, where the state pays just 5 percent, could be an attractive proposition.

But even a 5 percent payment responsibility gives many states pause. Instead, some may be eyeing other strategies to improve coverage and affordability for lower-income consumers next year using the state innovation waiver program, under which they could receive 100 percent of the marketplace subsidy amounts.

The state innovation waivers, by the way, are yet another possible route towards increasing coverage … but at the federal level, making arrangements to cover that final 5 percent of BHP expenses would, like my 90 percent Medicaid idea, likely encourage at least a few more states to go for it. I could see perhaps 2 million more covered by BHPs, though half of them would likely be cannibalized from QHPs.

Result: Perhaps 5 million more insured

Add all of the above up, and in the theoretical scenario where all of these ideas was passed into law (except for the undocumented immigrant allowance at the national level ... that actually seems more implausible than any of the other ideas I've listed) and had the results as I've spitballed, you'd end up with something like the following:

- 2.0 million eligible for ACA tax credits (down from 6.0 million)

- 3.0 million eligible for Medicaid (down from 5.0 million)

- 0.0 million eligible for S-CHIP (down from 3.0 million)

- 0.2 million caught in the Medicaid Gap (down from 2.7 million)

- 4.0 million undocumented immigrants (no change)

- 3.0 million ineligible for ACA tax credits due to having a standing ESI offer (down from 4.5 million)

- 2.0 million ineligible for ACA tax credits due to their income being above 400% FPL (down from 3.2 million)

- (+ 3 million who just won't Get Covered no matter what you do)

Total result: Around 15 million more covered

All of this should reduce the uninsured rate by another 15 million, leaving around 15 million still uninsured ... or around 5 percent of the total population (again, not counting that final, unattainable 3 million).

Steep hill to climb?

I realize that all of this involves a tremendous amount of effort, and most of the provisions seem very unlikely to happen given the current political climate. Combined, they would also require several hundred billion dollars of additional funding at the federal level (while also relieving the states of a good $140 billion in expenses).

Still, even $300-$400 billion or so per year (half for the feds taking over 30 percent of Medicaid costs from the states; the other half from other ideas I’ve listed) would still be far less than the $1.4 trillion which Sen. Sanders claims his plan would cost (or the $2.5 trillion per year which Kenneth Thorpe has estimated it would actually cost). Of course, it would still keep things messy and clunky, and still wouldn’t be universal … but it’d be another important step in getting there.

As difficult and messy as all of this (or even portions of it) would be to get through, and as incomplete as the results would be, the odds of getting these sorts of policy changes through (at least some of them, anyway) are still, in my honest opinion, far more obtainable than a wholesale overhaul of the entire system into a nationwide single-payer system.

There would still be much work left to do to achieve the remaining goals:

- Cover the remaining 15 million. (Again, 1 percent will fall through the cracks no matter what you do),

- Make sure the coverage is comprehensive and affordable for everyone,

- Deal with network issues and above all,

- Control prices.

The next phase to address these additional goals may involve steps such as my “drop the Medicare age one year at a time” idea. The larger point here, though, is that a series of changes (whether the ones I suggest or similar) are the only responsible way I can see pushing things forward in a way which seems at least somewhat realistic.

It’s not pretty, it’s not sexy, it’s not perfect and it would take several years to get through under the best of circumstances … but that’s how democracy works.

Charles Gaba is the founder of https://acasignups.net/, which has been live-tracking Obamacare enrollments since the exchanges launched in October 2013. His work has been cited by major publications from the Washington Post and Forbes to the New York Times as being the most reliable source available for up-to-date, accurate ACA enrollment data in the country.