Remember the public option? It was a linchpin of early Democratic health reform blueprints for what became the Affordable Care Act. The health insurance marketplace would be anchored by a government-run health plan that would work to keep costs low and make coverage as comprehensive as possible. Private insurers in the marketplace would have to compete against it.

The insurance industry lobbied hard against the public option, and the most conservative Democratic senators killed it. (Every Democratic vote was needed to pass the law, because Republicans rejected it en masse.)

When the ACA passed without a public option in 2010, some observers speculated that Congress might come back to establish one at a later point, if competition among private insurers proved a force too weak to keep coverage affordable. But that is clearly not going to happen on a national level with Republicans in control of Congress.

There is one way a public option could become a reality in fairly short order, however. The ACA didn’t create one market for health insurance, but rather 51 markets – one for each state plus the District of Columbia. And states have considerable freedom to shape their insurance markets, should they wish to seize it. “Nothing in the ACA stands in the way of a state creating a public option,” notes Larry Levitt, senior vice president for special initiatives at the Kaiser Family Foundation.

While no state has yet moved to create a public option, two states, Minnesota and New York, have taken what might be understood as a halfway step – or else an alternate route to more affordable care. That is, they have deployed a state-run Basic Health Program (BHP) that provides comprehensive coverage at very low premiums to state residents with household incomes below 200 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL).

To date, about two-thirds of enrollees in private plans offered in the ACA marketplace are in households with incomes below that threshold. The as-yet unanswered challenge for states committed to making the ACA work for all their citizens is to make coverage more affordable for people with somewhat higher incomes. As we will see, though, Minnesota may be poised to take a large step in that direction.

The challenge: Strengthening the “Affordable” in Affordable Care Act

Why might a state want to consider altering the ACA’s current benefit structure? The ACA has reduced the ranks of the uninsured by some 17 million. Various surveys indicate that about 70 to 75 percent of ACA private plan holders are satisfied with their coverage.

Nonetheless, there’s an emerging consensus among policymakers and healthcare researchers that the ACA marketplace leaves significant numbers of private plan holders under-insured – and that “regardless of the subsidies, coverage is still too expensive” for many of the still-uninsured, as Daniel Meuse, Deputy Director of the State Health Reform Assistance Network at Princeton University, puts it. The problem is particularly acute for those with incomes above 200 percent of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL), who in 2015 comprised a bit more than a third of marketplace enrollees.

Below that threshold, buyers who select Silver plans receive not only premium subsidies but strong Cost Sharing Reduction (CSR) subsidies that leave them with lower out-of-pocket costs than those paid by most people who get their health insurance from their employer. CSR weakens sharply at 200 percent FPL, however, and fades out entirely at 250 percent FPL. At the same time, premium subsidies are calculated to leave higher earners paying a much higher percentage of their incomes in premiums.

Here’s how the difference might typically play out. A Silver plan that carries a deductible of $0 or $250 will cost a single person with an income of $17,000 about $55 per month. If her income is $28,000, the same plan may have a $2,000 deductible and a monthly premium of $130. Bump the income up to $30,000, and the deductible may rise to $3,000 with a premium of $210.

Many of those seeking coverage at the higher income levels find those premiums and out-of-pocket costs daunting. According to a recent study, takeup of ACA plans by the uninsured falls off a cliff at 200 percent FPL, from 62 percent of eligible individuals below that level to 29 percent in the next band above.

A public option prototype of sorts

How might a state-run health plan offer residents more affordable care without increasing federal or state spending? In brief, by paying healthcare providers less than private insurers do and passing the savings to plan holders.

The Basic Health Program – a program the ACA will fund for states that opt in – works that way. The BHP is a state-run program offering insurance to residents who earn too much to qualify for Medicaid but less than 200 percent FPL. New York and Minnesota BHPs provide coverage through managed care organizations to which they pay rates comparable to or slightly above those they pay for Medicaid – rates much lower than those paid by most private insurers.

The BHPs provide comprehensive coverage at very low cost to enrollees. MinnesotaCare – which pre-existed the Affordable Care Act and was converted into a BHP as of January 1, 2015 – covers 96 to 99 percent of the average user’s yearly costs, with premiums topping out at $80 per month for those earning 200 percent FPL (compared to about $125 per month for benchmark Silver in the ACA marketplace). New York’s BHP is free to applicants with incomes ranging from 100 to 150 percent FPL, with zero copays. For those in the 150 t0 200 percent FPL range, the premium is $20 per month, with very low copays for specific services.

The problem with a BHP is that it leaves residents with incomes over 200 percent FPL – precisely those least well-served by the ACA marketplace – out in the cold.

The problem is particularly acute in Minnesota, because prior to ACA enactment, MinnesotaCare was available to childless adults with incomes up to 250 percent FPL and to parents up to 275 percent FPL. When it was converted into a BHP to tap federal funds devoted to that program, eligibility dropped to 200 percent FPL, sending those above that level into the subsidized private plan marketplace.

That created an “affordability cliff,” according to State Medicaid Direct Marie Zimmerman. A person crossing the 200 percent FPL line may go from an $80 premium and $34 deductible to a private Silver plan with a $107 premium and a deductible in the $1,400 range, according to Zimmerman.

Helping the not-so-poor

A state-appointed task force in Minnesota is scheduled to report on January 15 on options for smoothing out that cliff. One option under consideration is to apply for an “innovation waiver” to restore the 275 percent FPL threshold for MinnesotaCare, with somewhat higher premiums and coinsurance for those in the 200 to 250 percent FPL range and a sharper drop in coverage level for those over 250 percent FPL.

Under ACA innovation waivers, states can propose alternative schemes to meet the ACA’s affordability and coverage goals, with funding equivalent to what it would have cost to subsidize private plan holders under the existing structure. MinnesotaCare could then leverage the low rates it pays for medical care (via nonprofit managed care organizations) and low administrative costs to offer richer benefits to higher income buyers than those mandated by the ACA (though the state would pick up part of the cost).

If Minnesota does extend eligibility for MinnesotaCare to 275 percent FPL, the program will cover a large majority of those who would otherwise be eligible for subsidized private plans in the state’s ACA marketplace, MNSure. Almost everyone in the state who received financial help to obtain coverage would be in a public program rather than a private plan.

MinnesotaCare has the added advantage of being a well-regarded program that provides access to wider networks of hospitals and doctors than most state-run public programs – as well as offering comprehensive mental health and substance abuse coverage and innovative coordinated care programs. As it’s long been available to buyers well above the poverty line, it’s free of the stigma that attaches to Medicaid in many markets nationwide. It’s thus well positioned to attract enrollees to whatever income threshold it’s available to. It would also be a challenge for most states to replicate – MinnesotaCare has been around since 1992, and the state has a long history of striving to make quality coverage affordable to its residents. Paying Medicaid rates while fielding an adequate provider network is a high bar.

Options for expanding eligibility

One problem with extending MinnesotaCare eligibility is that it would reduce enrollment in Minnesota’s private plan exchange, which is already constrained because eligibility for subsidized private plans begins at an income level of 200 percent FPL, rather than 138 percent FPL as in states that do not have a BHP. Extending BHP eligibility to 275 percent FPL would wipe out most of the remaining subsidy-eligible private market. As it is, most Minnesotans who buy private plans do so off-exchange. And funding to run the exchange is dependent on the number of enrollees. The Minnesota Department of Health and Human Services estimates that the expansion would shift about 37,000 enrollees from subsidized private plans into MinnesotaCare.

Accordingly, an alternative option being considered by the task force is to use state funds to enrich subsidies offered in the private market, so that enrollees in the 200 to 275 percent FPL range get private coverage comparable to what they’d obtain in the BHP. But although the private plans in the Minnesota exchange are all nonprofit, they are paid higher rates than in the public program. Subsidizing the private market would therefore cost the state much more than expanding BHP eligibility. “Democrats wouldn’t let that happen,” says Lynn Blewett, a health policy professor at the University of Minnesota and member of the task force.

Another potential option for Minnesota was sketched out in a report prepared for the state by the Woodrow Wilson School at Princeton University in early 2015: Extend eligibility for MinnesotaCare to 400 percent FPL, the cutoff for subsidized private coverage under the ACA. Either give those at higher income levels a choice between buying in to MinnesotaCare or selecting a private plan, or simply eliminate the private marketplace for everyone who’s subsidy eligible. That’s more feasible in Minnesota than in most states, since a large majority of private plan holders buy their plans off-exchange (though that percentage is shrinking,as a spike in prices this year has rendered more buyers subsidy-eligible). While removing all or some subsidy-eligible buyers from the market might cause prices to rise for those who earn too much to qualify for subsidies, the impact would be less dramatic than in other states

The task force did not consider this option. Marie Zimmerman notes that though its costs have not been scoped out, it’s theoretically feasible. According to Lynn Blewett, however, “There is no political will to go that high.” And while the federal rules for seeking an innovation waiver are untested so far, guidelines just published this fall leave policymakers “pretty limited in what they can do,” according to Blewett.

Remixing ACA benefits

If MinnesotaCare were to be offered as a public option in the original sense, it would have to be offered on the same terms as private plans. That is, versions at pre-set coverage levels would each cover a fixed percentage of users’ average annual medical costs. And that fact highlights a little-recognized aspect of the ACA’s affordability problems.

The difficulty for subsidized buyers in the ACA marketplace comes not so much from the actual cost of insurance as from the ACA’s fixed subsidy and benefit formulas. If my income is $29,000, it doesn’t matter to me whether the premium paid to the insurer is $400 or $250: my subsidized premium for the benchmark Silver plan in my area will be a bit over 8 percent of my income, and the plan will be designed to cover 73 percent of my costs. (To the extent that the insurer pays less for care, my fixed share will also be smaller, but still substantial.)

It’s true that I can pick a plan that’s cheaper than the benchmark, and so pay less, but that plan will almost always be a bronze plan, which covers just 60 percent of average costs and generally has a deductible over $5,000. The problem for buyers with incomes over 200 percent FPL is that the ACA demands a large percentage of income for a plan that leaves them exposed to high out-of-pocket costs.

A state would need no waiver to put up a public option that conforms to the ACA subsidy structure. If that plan pays lower costs for care and administration than most private plans, consumers would benefit, as their fixed share of costs at each metal level would be a percentage of a lower overall amount.

To more radically improve affordability, though, a state-initiated public option would have to pass down the money saved by low payment rates and low administrative costs in the form of a richer benefit structure – as the two existing BHPs do for buyers under 200 percent FPL. To break the ACA formula structure – perhaps for private market insurers as well – the state would have to seek a waiver.

If Minnesota does opt to extend access to MinnesotaCare to the 275 percent FPL level, it will be providing a public plan to most of those who would be eligible to subsidized private plans if MinnesotaCare did not exist – probably about 90 percent of them. If the state were to extend eligibility to the 400 percent FPL level, it would offer the country a new model: public coverage for everyone deemed in need of financial assistance.

Andrew Sprung is a freelance writer who blogs about politics and policy, particularly health care policy, at xpostfactoid. His articles about the rollout of the Affordable Care Act have appeared in The Atlantic and The New Republic. He is the winner of the National Institute of Health Care Management’s 2016 Digital Media Award.

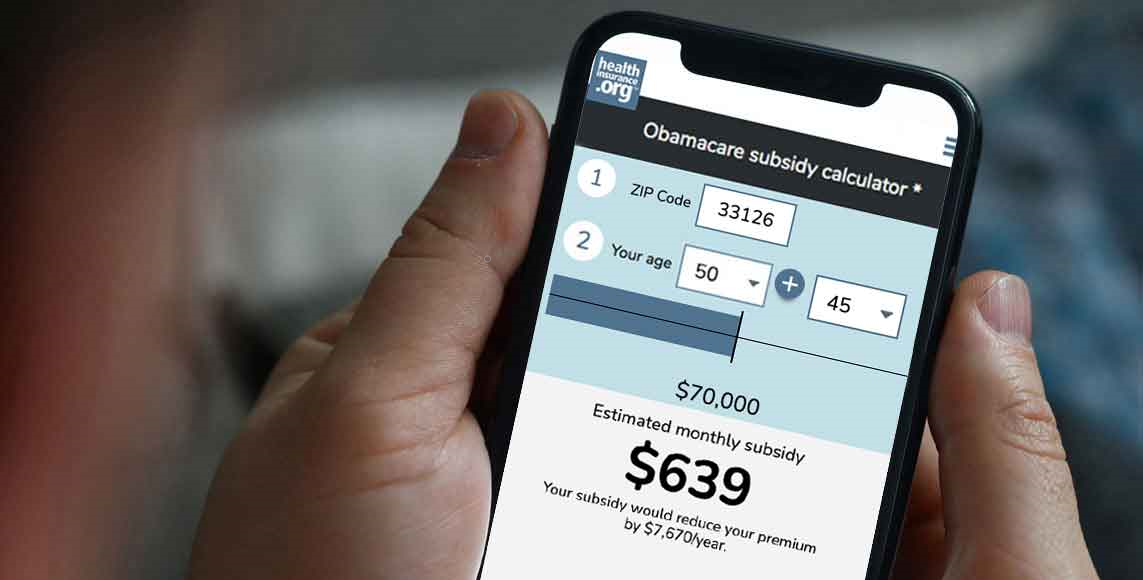

Get your free quote now through licensed agency partners!