Home > Health insurance Marketplace > California

California Marketplace health insurance in 2025

Compare ACA plans and check subsidy savings from a third-party insurance agency.

California health insurance Marketplace guide

Our California health insurance guide, including the FAQs below, is designed to help you understand the health coverage options and possible financial assistance available to you and your family. Having health coverage is especially necessary in California, as there’s a penalty on the state tax return for non-exempt filers who don’t have health coverage.3

California runs its own state-based health insurance Marketplace, called Covered California. A dozen private health insurers offer coverage for individuals and families via Covered California. And California is one of the states where the exchange still offers a platform small businesses can use to purchase health coverage for their employees; four insurers offer small group plans through Covered California for 2024.4

California is among the states where state-funded subsidies are available to Marketplace enrollees, in addition to federal subsidies. And California has allocated additional funding for the state subsidy program so that all Covered California enrollees will qualify for at least the Enhanced Silver 73 plan in 2025.5 with lower out-of-pocket costs and no deductibles.6

Under California rules, all of the plans sold in the exchange are standardized.7 Standardized plans are available in most states. But although most states also have non-standardized plans available through the exchange, California does not.8 This means that for certain services, all of the Covered California plans in a given metal level will have the same out-of-pocket costs.

A Covered California plan can be a great option if you need to buy your own health insurance. This includes people who aren’t eligible for Medicare or Medicaid, or don’t have an offer of affordable health insurance from an employer.

Frequently asked questions about health insurance in California

Who can buy health insurance on California’s Marketplace?

In order to sign up for private health coverage through Covered California, you must:9

- Be a California resident

- Not be incarcerated

- Not be enrolled in Medicare

- Be lawfully present in the United States; this includes DACA recipients as of the 2025 plan year.10 (California does allow low-income residents to enroll in Medi-Cal regardless of immigration status)

By those rules, most Californians can enroll in coverage through the exchange. But a bigger question for most people is financial assistance, and there are a few additional parameters to be eligible for subsidies through Covered California. To qualify for income-based Advance Premium Tax Credits (APTC), federal cost-sharing reductions (CSR), or California’s state-funded cost-sharing subsidies, you must:

- Not have access to affordable health coverage through an employer. If you have access to an employer’s plan but it seems too expensive, you can use our Employer Health Plan Affordability Calculator to see if you might qualify for premium subsidies via Covered California.

- Not be eligible for Medi-Cal (California Medicaid).

- Not be eligible for premium-free Medicare Part A.11

- File a joint tax return if you’re married.12

- Not be able to be claimed by someone else as a tax dependent.12

Beyond those basic parameters, qualifying for Covered California subsidies will depend on how much your household earns. Here’s how household income is calculated under the ACA.

California AB570, enacted in October 2021, makes California the first state in the country to provide a pathway for some policyholders to add their parents to their health plan as dependents.13

The legislation, which took effect in 2023, only applies to individual/family health plans (ie, not to plans that people get from an employer). Under the state law, a California resident with individual/family health coverage can cover parents as dependents, as long as the parents rely on the policyholder for at least 50% of their living expenses.

An earlier version of the bill would have applied to employer-sponsored health plans as well, but was opposed by business groups that worried about the cost. With the modification to make the legislation apply only to individual/family plans, the state expects that only about 15,000 people will use the option to add parents to their health plan.14

When can I enroll in an Affordable Care Act (ACA)-compliant plan in California?

California’s open enrollment period is longer than the window used in most other states. It begins November 1 and continues through January 31.15 (In most states, open enrollment runs from November 1 through January 15.) And for 2024 coverage, an extension through February 9, 2024 was added at the last minute.16

The open enrollment window is your opportunity to select a new plan or switch to a different plan. The enrollment window applies to plans obtained via Covered California or directly from an insurer, but note that subsidies are only available through Covered California.

For coverage to take effect on January 1, you need to complete your application by December 31. (This is later than the deadline in many other states.) If you enroll between January 1 and January 31, your coverage will take effect on February 1.17 (For 2024 coverage, the extension of open enrollment through February 9, 2024 gave people an additional nine days to sign up with coverage backdated to February 1.)16

After the annual open enrollment window ends, you may still be eligible to enroll or make a plan change if you experience a qualifying life event such as giving birth or losing other health coverage. And some people can enroll year-round even without a specific qualifying life event.18

In addition to the standard list of qualifying events that trigger special enrollment periods nationwide, Covered California will also grant a special enrollment period to a person whose medical provider leaves their health plan’s network while the person is undergoing treatment for one of the following:19

- Pregnancy

- A terminal illness

- An acute condition or serious chronic condition

- The care of a child during its first 36 months.

- A surgery or other procedure scheduled in the next 180 days

There is also a special enrollment period available if you have to pay the California penalty for not having health coverage the prior year.19

In 2022, California enacted SB967, which creates an easy enrollment program in California as of the 2023 tax year (ie, for tax returns filed in early 2024).20

Unlike most other states that have created or considered similar programs, the California legislation did not specifically create a special enrollment period for people deemed eligible for marketplace coverage (as opposed to Medicaid/CHIP, which is available year-round). However, Covered California does offer a special enrollment period specifically for people who have to pay a penalty on their state tax return for not having health insurance. A full list of Covered California’s special enrollment opportunities is available here.

Enrollment in Medi-Cal (California Medicaid) is available year-round.

How do I enroll in a Covered California Marketplace plan?

To enroll in an ACA Marketplace/exchange plan in California, you can:

- Visit Covered California, California’s health insurance exchange (Marketplace). Using this online platform, you can compare plans, determine whether you’re eligible for financial assistance, and enroll in coverage. You can reach the Covered California call center at 1-800-300-1506, Monday to Friday between 8 a.m. and 6 p.m.

- Enroll in a plan through Covered California with the help of an insurance agent or certified enrollment counselor.21

- Covered California has a “help on demand” program that allows you to submit your contact information and then receive a call from a certified enrollment assister who will help you sort out the details.

How can I find affordable health insurance in California?

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) provides income-based subsidies that can reduce the amount you pay for your coverage each month. In California, these subsidies are available to applicants who meet the eligibility requirements and enroll in a health plan through Covered California.

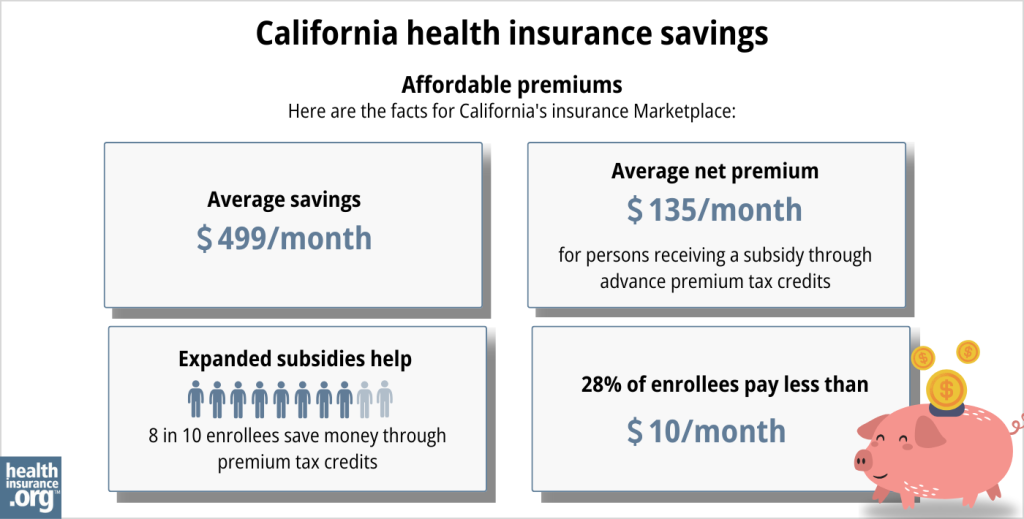

Nearly nine out of ten Covered California enrollees were receiving premium subsidies as of early 2024. These subsidies averaged about $523/month, and after the subsidies were applied, the average enrollee’s premium was about $186/month.22

If your household income isn’t more than 250% of the federal poverty level, you’ll also be eligible for federal cost-sharing reductions (CSR), which will reduce your deductible and other out-of-pocket expenses. These benefits are built into Silver-level plans if the applicant is eligible for them. Forty-four percent of Covered California enrollees were receiving CSR benefits as of 2024.23

And as of 2024, California is supplementing the federal CSR benefits with additional state-funded cost-sharing subsidies. Eligible Silver-plan enrollees have $0 deductibles and lower costs for other out-of-pocket expenses.24

California has allocated additional funding to the state subsidy program for 2025. This will ensure that all Covered California enrollees will qualify for at least the Enhanced Silver 73 plan,5 which offers reduced out-of-pocket costs and no deductibles.6

Covered California and Medi-Cal (California Medicaid) use the same application, and the system will let you know whether you’re eligible for Medi-Cal or a private plan through Covered California – with subsidies if you qualify for them.

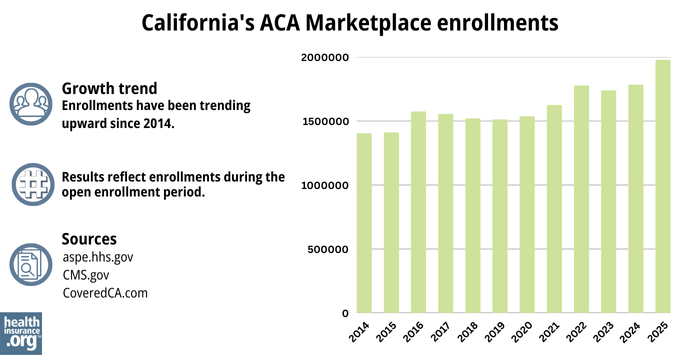

Source: CMS.gov 25

California does not allow short-term health insurance policies to be sold, under the terms of legislation that the state enacted in 2018.26

How many insurers offer coverage in California’s Marketplace?

Twelve insurers will offer plans through Covered California for 2025.6

This is unchanged from 2024, when the same 12 insurers offered coverage. But there was one insurer exit at the end of 2023 and one newcomer for 2024. (Oscar Health Plan of California left at the end of 2023, while Inland Empire Health Plan was new for 2024.)27

Are Marketplace health insurance premiums increasing in California?

The following average rate changes have been approved for 2025 for the insurers that offer plans through Covered California, amounting to an overall average rate increase of 7.7%.28 (This is slightly lower than the 7.9% average rate increase that insurers initially filed in California,6 because the approved rates were slightly lower for several of the carriers.29)

California’s ACA Marketplace Plan 2025 APPROVED Rate Increases by Insurance Company |

|

|---|---|

| Issuer | Percent Increase |

| Aetna CVS Health | 15.4% |

| Anthem Blue Cross | 12.7% |

| Blue Shield of California | 8% |

| Balance by CCHP | 4% |

| Health Net | 6.5% |

| Inland Empire Health Plan | 1.8% |

| Kaiser Permanente | 6.4% |

| LA Care Health Plan | 6.2% |

| Molina Healthcare | 6.4% |

| Sharp Health Plan | 5.7% |

| Valley Health Plan | 9% |

| Western Health Advantage | 3.9% |

Source: Covered California6 and the California Department of Managed Healthcare30

It’s important to remember that average rate changes are for full-price plans (i.e. before any subsidies are applied), and most enrollees do not pay full price: Nearly nine out of ten Covered California enrollees were receiving premium subsidies in 2024, to offset some or all of their monthly payments.31

The subsidy amount is different for each enrollee and changes each year depending on the cost of the second-lowest-cost Silver plan relative to the enrollee’s household income. Under the American Rescue Plan and the Inflation Reduction Act, subsidies are larger and more widely available than they used to be, and that will continue to be true at least through 2025.

Full-price (unsubsidized) premium changes depend on the specific plan (for each insurer, premium changes vary from one plan to another), as well as the enrollee’s age and zip code.

So, for the majority of Covered California enrollees, net premium changes will depend on how their specific plan’s rate changes, as well as year-over-year changes in their subsidy amount.

If the cost of your current plan is increasing for the coming year, you may want to consider some of the other plans that are available via Covered California. You might find some that are less expensive and offer similar benefits.

Here’s a look at how average full-price (pre-subsidy) premiums have changed over the years in California’s individual/family market:

How many people are insured through California’s Marketplace?

What health insurance resources are available to California residents?

Covered California: This is California’s Marketplace/exchange. Residents can use Covered California to enroll in individual/family health plans and receive income-based subsidies, and also to enroll in Medi-Cal. You can contact Covered California at 800-300-1506.

California Department of Health Care Services: The agency that administers Medi-Cal and various other health care programs.

California Department of Managed Health Care (DMHC): Regulates the vast majority of California’s commercial (non-self-insured) health plans, and assists consumers and businesses with insurance-related questions and concerns.

California Department of Insurance: Regulates California’s insurance plans that aren’t regulated by the DMHC. If a complaint or concern is filed with the DMHC and it’s for a product that’s regulated by the Department of Insurance, it will be forwarded to the Department of Insurance.

California Health Insurance Counseling and Advocacy Program (HICAP): A service for California Medicare beneficiaries and their caregivers. HICAP provides information and assistance with questions related to Medicare eligibility, enrollment, and claims.

Louise Norris is an individual health insurance broker who has been writing about health insurance and health reform since 2006. She has written dozens of opinions and educational pieces about the Affordable Care Act for healthinsurance.org.

Looking for more information about other options in your state?

Need help navigating health insurance options in California?

Explore more resources for options in California including short-term health insurance, dental insurance, Medicaid and Medicare.

Speak to a sales agent at a licensed insurance agency.

Footnotes

- ”2025 OEP State-Level Public Use File (ZIP)” Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Accessed May 13, 2025 ⤶ ⤶

- ”Covered California’s Rates and Plans for 2025: The Most Financial Support Ever to Help More Californians Pay for Health Insurance” Covered California. July 24, 2024 ⤶

- “Penalty” CoveredCA.com, Accessed August 2023 ⤶

- Covered California for Small Business, Health and Dental Plans. Covered California. Accessed December 2023. ⤶

- ”Covered California Policy and Action Items” Covered California Board Meeting.May 16, 2024 ⤶ ⤶

- ”Covered California’s Rates and Plans for 2025: The Most Financial Support Ever to Help More Californians Pay for Health Insurance” Covered California. July 24, 2024 ⤶ ⤶ ⤶ ⤶ ⤶

- “Covered California 2024 Patient-Centered Benefit Plan Designs” CoveredCA.com, June 16, 2022 ⤶

- “Standardized Plans in the Health Care Marketplace: Changing Requirements” KFF.org, May 8, 2023 ⤶

- “Who can get a health plan through Covered California?” CoveredCA.com, Accessed August 2023 ⤶

- ”Biden-Harris Administration Finalizes Policies to Increase Access to Health Coverage for DACA Recipients” CMS.gov. May 3, 2024 ⤶

- Medicare and the Marketplace, Master FAQ. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Accessed November 2023. ⤶

- Premium Tax Credit — The Basics. Internal Revenue Service. Accessed MONTH. ⤶ ⤶

- California Assembly Bill 570. BillTrack50. Enacted October 2021. ⤶

- California Now 1st State To Let Parents Be Added To Their Children’s Insurance Plans. CBS News Sacramento. October 2021. ⤶

- “Dates and Deadlines” CoveredCA.com Accessed August 2023 ⤶

- Covered California Announces More Time to Enroll for Coverage in 2024. Covered California. January 31, 2024. ⤶ ⤶

- “When will my coverage start?” CoveredCA.com, Accessed August 2023 ⤶

- “Who doesn’t need a special enrollment period?“ healthinsurance.org, Accessed August 2023 ⤶

- Qualifying Life Events. Covered California. Accessed December 2023. ⤶ ⤶

- California Senate Bill 967. BillTrack50. Enacted August 2022. ⤶

- “Help With Your Application” CoveredCA.com, Accessed August 2023 ⤶

- ”Effectuated Enrollment: Early 2024 Snapshot and Full Year 2023 Average” CMS.gov, July 2, 2024 ⤶

- ”Effectuated Enrollment: Early 2024 Snapshot and Full Year 2023 Average” CMS.gov, July 2, 2024 ⤶

- “Covered California to Launch State-Enhanced Cost-Sharing Reduction Program in 2024 to Improve Health Care Affordability for Enrollees” CoveredCA.com, July 20, 2023 ⤶

- “2025 Marketplace Open Enrollment Period Public Use Files” CMS.gov, May 2025 ⤶

- California Senate Bill 910. BillTrack50. Enacted September 2018. ⤶

- “Covered California’s Health Plans and Rates for 2024: More Affordability Support and Consumer Choices Will Shield Many From Rate Increase” CoveredCA.com, July 25, 2023 ⤶

- ”California: *Final* avg. unsubsidized 2025 ACA rate changes: +7.7% individual market, +7.3% small group market” ACA Signups. Oct. 10, 2024 ⤶

- ”Search Rate Review Filings” California Department of Managed Health Care. Accessed Oct. 10, 2024 (Compare initial filings in Covered CA press release with approved rates) ⤶

- ”Search Rate Review Filings” California Department of Managed Health Care. Accessed Oct. 10, 2024 ⤶

- “Effectuated Enrollment: Early 2024 Snapshot and Full Year 2023 Average” CMS.gov, Accessed Aug 15, 2024 ⤶

- Covered California Announces Rates for 2015; Rigorous Negotiations with Health Insurance Companies Keep Rate Increases Low and Choices Robust. Covered California. July 2014. ⤶

- Covered California Holds Rate Increases Down For Second Consecutive Year. Covered California. July 2015. ⤶

- Covered California Health Plan Rates To Jump 13.2 Percent In 2017. KFF Health News. July 2016. ⤶

- 2018 Rate Hikes. ACA Signups. October 2017. ⤶

- Covered California Releases 2019 Individual Market Rates: Average Rate Change Will Be 8.7 Percent, With Federal Policies Raising Costs. Covered California. July 2018. ⤶

- 2020 Rate Changes. ACA Signups. October 2019. ⤶

- California’s Efforts to Build on the Affordable Care Act Lead to a Record-Low Rate Change for the Second Consecutive Year. Covered California. August 2020. ⤶

- Covered California Announces 2022 Plans: Full Year of American Rescue Plan Benefits, More Consumer Choice and Low Rate Change. Covered California. July 2021. ⤶

- UPDATED: FINAL Unsubsidized 2023 Premiums: +6.2% Across All 50 States +DC. ACA Signups. Accessed November 2023. ⤶

- Covered California’s Health Plans and Rates for 2024: More Affordability Support and Consumer Choices Will Shield Many From Rate Increase. CoveredCA.com, July 25, 2023 ⤶

- ”Health Insurance Marketplaces 2024 Open Enrollment Period Report” CMS.gov. March 22, 2024 ⤶

- “Health Insurance Marketplace: Summary Enrollment Report for the Initial Annual Open Enrollment Period” HHS; ASPE, 2015 ⤶

- “Health Insurance Marketplaces 2015 Open Enrollment Period: March Enrollment Report ”, HHS; ASPE, 2015 ⤶

- “Health Insurance Marketplaces 2016 Open Enrollment Period: Final Enrollment Report” HHS; ASPE, 2016 ⤶

- “2017 Marketplace Open Enrollment Period Public Use Files ” CMS.gov, 2017 ⤶

- “ 2018 Marketplace Open Enrollment Period Public Use Files ” CMS.gov, 2018 ⤶

- “2019 Marketplace Open Enrollment Period Public Use Files ” CMS.gov, 2019 ⤶

- “ 2020 Marketplace Open Enrollment Period Public Use Files ” CMS.gov, 2020 ⤶

- “ 2021 Marketplace Open Enrollment Period Public Use Files ” CMS.gov, 2021 ⤶

- “ 2022 Marketplace Open Enrollment Period Public Use Files ” CMS.gov, 2022 ⤶

- “ Health Insurance Marketplaces 2023 Open Enrollment Report ” CMS.gov, 2023 ⤶

- ”HEALTH INSURANCE MARKETPLACES 2024 OPEN ENROLLMENT REPORT” CMS.gov, 2024 ⤶

- ”Covered California Reaches Landmark Achievement with Nearly 2 Million Enrolled as Open Enrollment Concludes” CoveredCA.com, February 20, 2025 ⤶