Home > States > Health insurance in New Jersey

See your New Jersey health insurance coverage options.

Find individual and family plans, small-group, short-term or Medicare plans through licensed agency partners.

New Jersey Health Insurance Consumer Guide

This New Jersey health insurance guide is designed to help you understand the coverage options and potential financial assistance that may be available to you and your family.

Starting in the fall of 2020, New Jersey began using its own state-run health insurance exchange (Marketplace) – GetCoveredNJ. Prior to that, the state used the federally run HealthCare.gov Marketplace platform.

GetCoveredNJ is a place where New Jersey residents can shop for individual and family health plans offered by various private health insurance carriers. These plans are used by people who aren’t eligible for Medicare, Medicaid, or an affordable employer-sponsored health plan. For 2024 coverage, New Jersey’s Marketplace will offer plans from six insurers (plan availability varies by area), including UnitedHealthcare, which is new for 2024.1

In addition to federal premium subsidies and cost-sharing reductions, New Jersey also offers state-funded premium subsidies. The program, called New Jersey Health Plan Savings, is available to GetCoveredNJ enrollees with household incomes up to 600% of the poverty level.2

New Jersey is one of the few states that has its own individual mandate, which means residents who don’t have health insurance can be subject to a penalty on the state tax return.3

Explore our other comprehensive guides to coverage in New Jersey

Dental coverage in New Jersey

Want to improve your smile and save money when you visit the dentist? It might make sense to purchase dental insurance, in addition to your medical coverage. Our guide explains dental coverage options in New Jersey.

New Jersey’s Medicaid program

New Jersey Family Care, the state’s Medicaid/CHIP program, covers about 2.2 million low-income residents. New Jersey expanded Medicaid under the ACA, and New Jersey Family Care enrollment grew by 76% from 2013 to early 2023.4

Medicare coverage and enrollment in New Jersey

More than 1.7 million New Jersey residents were enrolled in Medicare as of 2023.5 Our New Jersey Medicare guide explains the various parts of Medicare, coverage options under Medicare Advantage and Part D, and New Jersey rules regarding Medigap (Medicare Supplement) availability.

Short-term health insurance coverage in New Jersey

New Jersey law requires all health plans sold to individuals in New Jersey to provide “comprehensive benefits that exceed the requirements of the Affordable Care Act” and the plans must be guaranteed issue, guaranteed renewable, and provide full-year coverage.6 These long-standing provisions are incompatible with short-term health insurance, so short-term policies are not available for purchase in the state.

Frequently asked questions about health insurance in New Jersey

Who can buy Marketplace health insurance in New Jersey?

To be eligible to enroll in private health coverage through GetCoveredNJ, you must:7

- Live in New Jersey and be lawfully present in the United States

- Not be incarcerated

- Not be enrolled in Medicare

So most New Jersey residents are eligible to enroll in a health plan through the exchange.8 But a bigger question for most people is eligibility for financial assistance, and there are some additional parameters must be met in order to qualify for state and federal subsidies through GetCoveredNJ.

To qualify for income-based Advance Premium Tax Credits (APTC), federal cost-sharing reductions (CSR), or New Jersey’s Health Plan Savings subsidies, you must:

- Not be eligible to enroll in an affordable plan offered by an employer. If you have access to an employer’s plan and aren’t sure whether it’s considered affordable, you can use our Employer Health Plan Affordability Calculator to see if you might qualify for premium subsidies via GetCoveredNJ.

- Not be eligible for New Jersey Family Care (Medicaid or CHIP), or for premium-free Medicare Part A.9

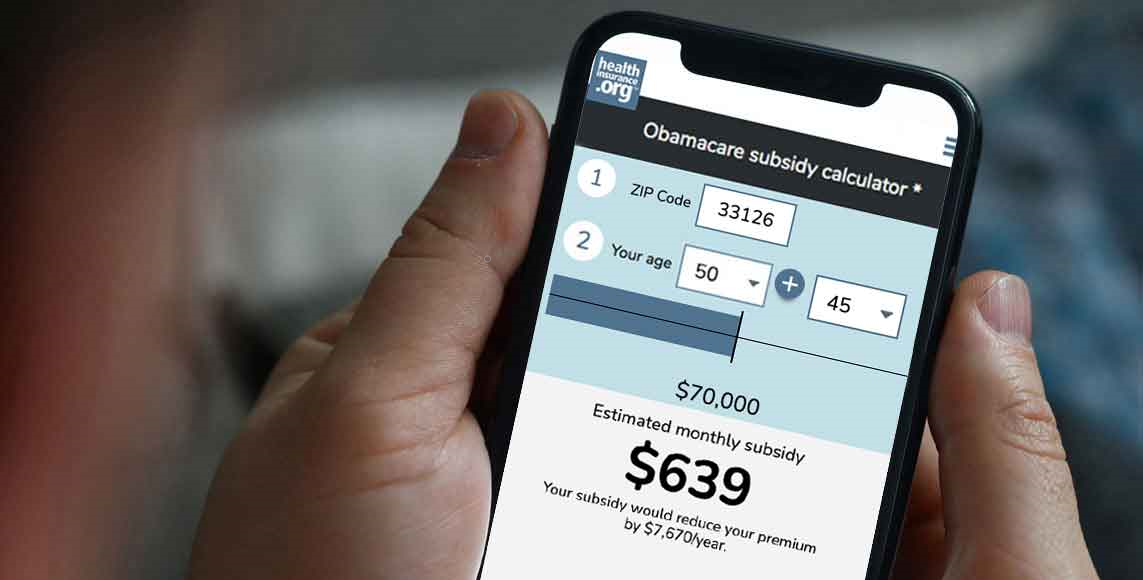

In addition to those basic parameters, qualifying for subsidies through GetCoveredNJ depends on your household’s income and how that compares with the cost of the second-lowest-cost Silver plan in your area – which depends on your age and location.

When can I enroll in an ACA-compliant plan in New Jersey?

In New Jersey, the open enrollment period begins November 1 and continues through January 31.10 This is a couple weeks longer than the enrollment window used in most other states.

For coverage to take effect on January 1, your application needs to be completed by December 31,11 which is later than the deadline in most other states. If you enroll in January, your new coverage will take effect on February 1.12

Outside of the annual open enrollment period, you may be eligible to enroll or make a plan change if you experience a qualifying life event, such as giving birth or losing other health coverage.

New Jersey is one of several states where pregnancy is considered a qualifying life event, allowing a pregnant woman to enroll in health coverage during the pregnancy (in most states, the birth of a baby is a qualifying event, but pregnancy is not).13

New Jersey has enacted legislation to create an “easy enrollment” program that will be in use as of early 2024, helping uninsured people get connected with health coverage via their state tax returns. 14

And some people can enroll year-round even without a specific qualifying life event.

Enrollment in New Jersey Family Care (Medicaid and CHIP) is available year-round.

How do I enroll in a Marketplace plan in New Jersey?

To enroll in an ACA Marketplace/exchange plan in New Jersey, you can:

- Visit GetCoveredNJ, New Jersey’s health insurance exchange, to compare available health plans, determine whether you’re eligible for financial assistance (including federal and state subsidies), and enroll in coverage, either during open enrollment or during a special enrollment period.

- Enroll in a GetCoveredNJ plan the help of licensed agents, navigators, or certified application counselors.15

You can reach GetCoveredNJ’s call center at 1-833-677-1010 TTY 711

How can I find affordable health insurance in New Jersey?

As a result of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), federal income-based subsidies (APTC) are available to lower the amount you pay for your health coverage each month. These subsidies are available to enrollees who meet the eligibility requirements and select a metal-level health plan through GetCoveredNJ.

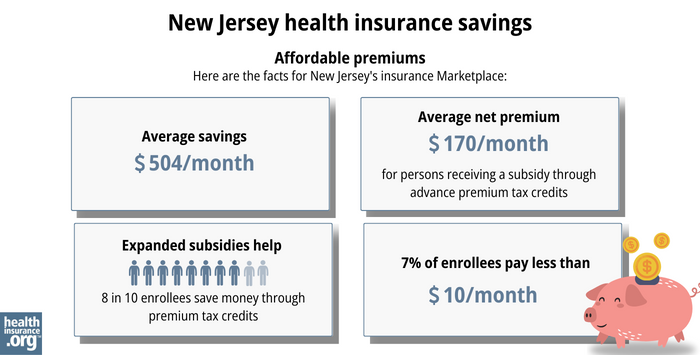

Eighty-eight percent of GetCoveredNJ enrollees were receiving premium subsidies as of early 2023. These subsidies paid an average of $504/month, reducing the average enrollee’s premium to about $170/month.16

Source: CMS.gov16

In addition, New Jersey is among the states where additional state-funded subsidies are available. The New Jersey Health Plan Savings subsidies are available to enrollees with household incomes up to 600% of the federal poverty level. (For 2024 coverage, that’s $87,480 for a single individual, and $180,000 for a family of four.)17

The state-funded subsidies are added on top of the federally-provided APTC, further reducing the amount that people have to pay for their health coverage in New Jersey.

Applicants with household income up to 250% of the federal poverty level are also eligible for federal cost-sharing reductions (CSR), which will reduce the deductible and other out-of-pocket expenses for Silver-level plans. Nearly half of GetCoveredNJ enrollees were receiving CSR benefits as of 2023.18

If you’re eligible for premium subsidies (including APTC and NJ Health Plan Savings subsidies) as well as CSR, you can use them both if you select a Silver-level plan through GetCoveredNJ. (APTC and NJ Health Plan Savings subsidies can be used with plans at any metal level, but CSR benefits are only available on Silver plans.)

Although most GetCoveredNJ enrollees do qualify for premium subsidies, New Jersey is also among the states that have created reinsurance programs. This helps to keep unsubsidized premiums lower than they would otherwise be.19

Depending on your income and circumstances, you may be able to enroll in free or low-cost health coverage through New Jersey Family Care. Learn more about whether you might be eligible for these programs in New Jersey.

How many insurers offer Marketplace coverage in New Jersey?

Six insurers offer plans through New Jersey’s exchange for 2024, including one newcomer.20

Are Marketplace health insurance premiums increasing in New Jersey?

For 2024, average full-price premiums in the individual market in New Jersey increased by 4.4%.

For 2024, the following average rate changes have been approved for New Jersey’s Marketplace insurers:

New Jersey’s ACA Marketplace Plan 2024 Approved Rate Increases by Insurance Company |

|

|---|---|

| Issuer | Percent Increase |

| AmeriHealth Ins. Co. of NJ | 3.8% |

| Horizon Healthcare Services (BCBS) | 4.2% |

| Oscar Health | 6.7% |

| WellCare/Ambetter | 8.3% |

| Aetna | 5.4% |

| UnitedHealthcare | new for 2024 |

Source: HealthCare.gov, and the New Jersey Department of Banking and Insurance.21

In addition, there are two off-exchange-only carriers – AmeriHealth HMO and Oxford – with approved average rate increases of 4.3% and 13.8%, respectively, for 2024.22

Average rate changes apply to full-price premiums, and most enrollees do not pay full price: Eighty-eight percent of GetCoveredNJ’s enrollees were receiving federal premium subsidies in 2023.18 These subsidies are larger and more widely available than they used to be, due to the American Rescue Plan and the Inflation Reduction Act.23

For perspective, here’s an overview of how average unsubsidized premiums in the individual market in New Jersey have changed over the years:

- 2015: Average increase of 2%.24

- 2016: Average increase of 10.2%.25

- 2017: Average increase of 8.8%.26

- 2018: Average increase of 22%.27

- 2019: Average decrease of 9.3%.28 (Reinsurance program took effect)

- 2020: Average increase of 8.7%.29

- 2021: Average increase of 3.3%.30

- 2023: Average increase of 8.8%.31

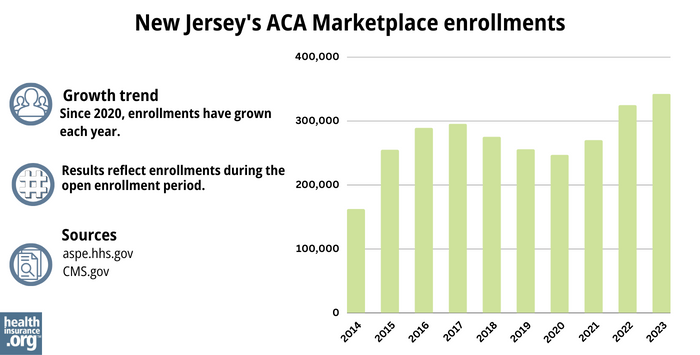

How many people are insured through New Jersey’s Marketplace?

What health insurance resources are available to New Jersey residents?

GetCoveredNJ (also called Get Covered New Jersey)

New Jersey’s Marketplace/exchange. Residents who need to buy their own health insurance can use GetCoveredNJ to enroll in coverage and receive income-based subsidies. You can contact GetCoveredNJ at r 1-833-677-1010 TTY 711.

New Jersey Division of Insurance

Regulates New Jersey’s insurance industry, and assists consumers and businesses with insurance-related questions and concerns.

New Jersey Family Care

Includes Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP).

New Jersey State Health Insurance Assistance Program

A resource for people with questions about Medicare in New Jersey.

Louise Norris is an individual health insurance broker who has been writing about health insurance and health reform since 2006. She has written dozens of opinions and educational pieces about the Affordable Care Act for healthinsurance.org.

Footnotes

- ”UnitedHealthcare to Offer Individual and Family Plans on the Health Insurance Marketplace in 26 States for 2024” UnitedHealthGroup. October 2023. ⤶

- “Lower Your Monthly Premiums with the NJ Health Plan Savings” GetCoveredNJ. ⤶

- New Jersey’s Health Coverage Requirement. New Jersey Department of the Treasury. Accessed November 2023. ⤶

- "Total Monthly Medicaid & CHIP Enrollment and Pre-ACA Enrollment" KFF. April 2023 ⤶

- "Medicare Monthly Enrollment" CMS.gov, April 2023 ⤶

- “2009 New Jersey Code TITLE 17B - INSURANCE 17b:27A 17B:27A-3 - Individual health benefits plans, applicability of act” Justia US Law ⤶

- ”A quick guide to the Health Insurance Marketplace” HealthCare.gov ⤶

- “Who can shop on GetCoveredNJ” GetCoveredNJ, Accessed September 2023 ⤶

- Medicare and the Marketplace, Master FAQ. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Accessed November 2023. ⤶

- “What is an open enrollment period?” GetCoveredNJ Frequently Asked Questions. ⤶

- “If I sign up during open enrollment, when will my coverage start?” GetCoveredNJ Frequently Asked Questions, Accessed September 2023 ⤶

- “When can you get health insurance?” HealthCare.gov, 2023 ⤶

- Special Enrollment Period (SEP) Overview. GetCoveredNJ. Accessed December 2023. ⤶

- New Law Establishing the New Jersey Easy Enrollment Health Insurance Program Aims to Improve Access to Affordable Health Coverage for Residents. New Jersey Department of Banking and Insurance. July 2022 ⤶

- Find Local Assistance. GetCoveredNJ. Accessed November 2023. ⤶

- “2023 Marketplace Open Enrollment Period Public Use Files”CMS.gov, March 2023 ⤶ ⤶ ⤶

- “Lower Your Monthly Premiums with the NJ Health Plan Savings” GetCoveredNJ ⤶

- “Effectuated Enrollment: Early 2023 Snapshot and Full Year 2022 Average”CMS.gov, March 15, 2023. ⤶ ⤶

- New Jersey’s ACA Section 1332 State Innovation Waiver. New Jersey Department of Banking and Insurance. Accessed November 2023. ⤶

- ICYMI: Open Enrollment at Get Covered New Jersey Starts Today, With More Plan Options and Historic Levels of Financial Help Available. State of New Jersey, Governor Phil Murphy. November 1, 2023. ⤶

- “New Jersey Rate Review Submissions” HealthCare.gov, Accessed November 2023. And 2024 IHC/SEH Average Rate Changes. New Jersey Department of Banking and Insurance. Accessed November 2023. ⤶

- “New Jersey Rate Review Submissions” HealthCare.gov, Accessed November 2023 ⤶

- “Health Insurance Marketplaces 2023 Open Enrollment Report”CMS.gov, Accessed August 2023 ⤶ ⤶

- Analysis Finds No Nationwide Increase in Health Insurance Marketplace Premiums. The Commonwealth Fund. December 2014. ⤶

- FINAL PROJECTION: 2016 Weighted Avg. Rate Increases: 12-13% Nationally* ACA Signups. October 2015. ⤶

- Avg. UNSUBSIDIZED Indy Mkt Rate Hikes: 25% (49 States + DC). ACA Signups. October 2016. ⤶

- New Jersey: Approved 2018 Rate Hikes: 22% On Average, Over Half Due Specifically To CSR/Mandate Sabotage. ACA Signups. October 2017. ⤶

- 2019 Rate Hikes. ACA Signups. October 2018. ⤶

- NJ Department of Banking and Insurance Releases Health Plan Rates. New Jersey Department of Banking and Insurance. October 2019. ⤶

- NJ Department of Banking and Insurance Announces 2021 Health Insurance Rate Changes, Lower Premiums Available for Most Marketplace Enrollees Due to New State Subsidies. New Jersey Department of Banking and Insurance. September 2020.

- 2022: Average increase of 7.9%.[efn_note]NJ Department of Banking and Insurance Announces More Health Insurance Offerings in 2022, Record Levels of Financial Help Available for Another Year at Get Covered New Jersey. New Jersey Department of Banking and Insurance. September 2021. ⤶

- “NJ Department of Banking and Insurance Announces Expanded Health Insurance Options in 2023, Historic Levels of Financial Help Remain Available at Get Covered New Jersey” New Jersey Department of Banking and Insurance, Sept. 30, 2022. ⤶

- “ASPE Issue Brief (2014)” ASPE, 2015 ⤶

- “Health Insurance Marketplaces 2015 Open Enrollment Period: March Enrollment Report”, HHS.gov, 2015 ⤶

- “HEALTH INSURANCE MARKETPLACES 2016 OPEN ENROLLMENT PERIOD: FINAL ENROLLMENT REPORT” HHS.gov, 2016 ⤶

- “2017 Marketplace Open Enrollment Period Public Use Files” CMS.gov, 2017 ⤶

- “2018 Marketplace Open Enrollment Period Public Use Files” CMS.gov, 2018 ⤶

- “2019 Marketplace Open Enrollment Period Public Use Files” CMS.gov, 2019 ⤶

- “2020 Marketplace Open Enrollment Period Public Use Files” CMS.gov, 2020 ⤶

- “2021 Marketplace Open Enrollment Period Public Use Files” CMS.gov, 2021 ⤶

- “2022 Marketplace Open Enrollment Period Public Use Files” CMS.gov, 2022 ⤶