Medicaid eligibility and enrollment in Utah

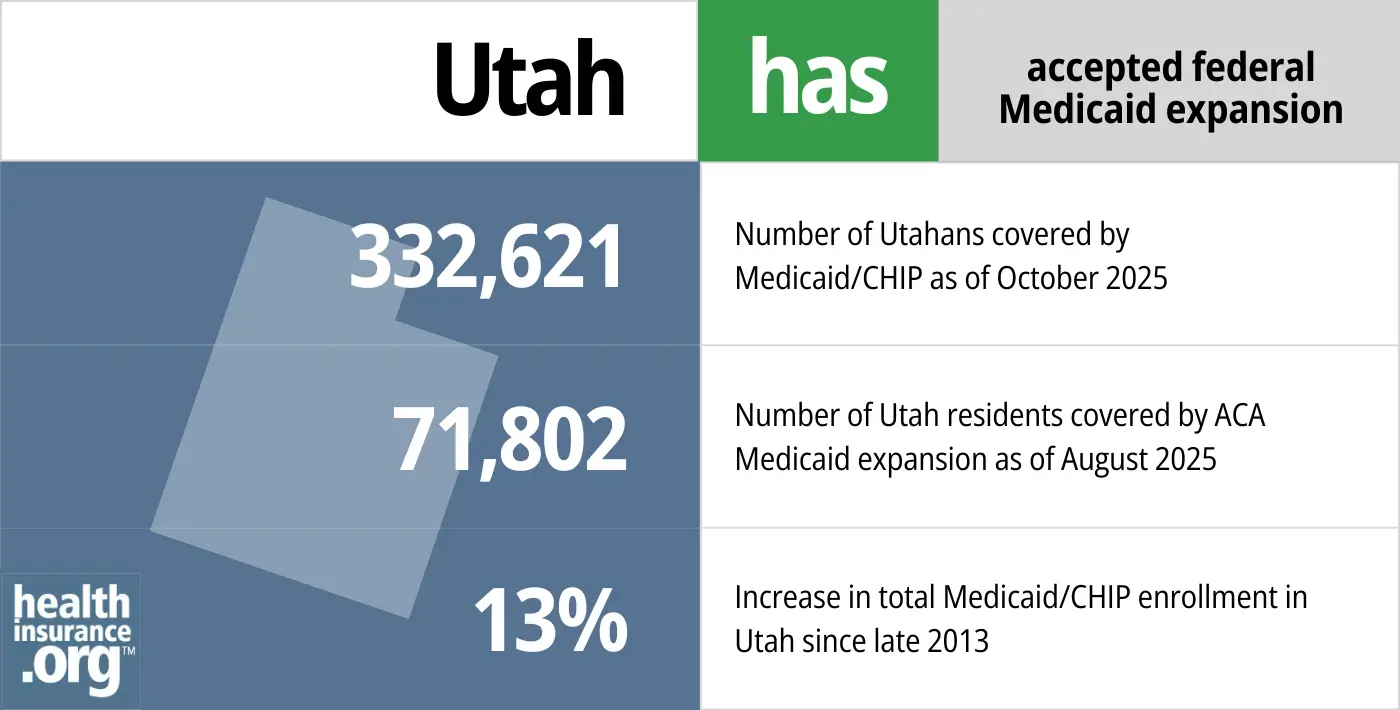

Utah’s Medicaid expansion took effect in January 2020, and covers 72,000 low-income adults.

Who is eligible for Medicaid in Utah?

Medicaid coverage in Utah is available under the following eligibility rules1 (these numbers include a built-in 5% income disergard that’s added to the regular eligibility limits).2

- Pregnant women with household income up to 144% of poverty are eligible for Medicaid. The mother receives full Medicaid coverage throughout the pregnancy and for 12 months postpartum.3

- Children with household incomes up to 205% of poverty are eligible for either Utah Medicaid or CHIP.

- Women with household incomes up to 250% of poverty are eligible for certain cancer screenings through the Utah Cancer Control Program (UCCP). If they are found to have breast or cervical cancer during the screening, they are eligible for full Medicaid coverage. If they have a precancerous condition (breast or cervical), they are eligible for three months of Medicaid coverage.

- Adults under age 65 (with or without dependent children) in Utah can get Medicaid coverage if their household income is up to 138% of the poverty level. This is due to Medicaid expansion under the ACA, which took effect in Utah in January 2020 under the terms of a voter-approved ballot measure.

- Utah provides Medicaid for various other select populations – check their list to see if you might be in any of the eligible groups (note that these other populations are subject to both income and asset limits to qualify for Medicaid).

for 2026 coverage

0.0%

of Federal Poverty Level

Apply for Medicaid in Utah

You can enroll online through HealthCare.gov or the state’s Medicaid website; by phone at 800-318-2596; or by mail, fax, or in person at a local office.

Eligibility: Coverage is available for low-income aged, blind, and disabled residents. It's also available for pregnant women with incomes up to 139% of poverty, children with incomes up to 200% of poverty, and adults with incomes up to 100% of poverty. Utah’s guidelines also provide for other groups to obtain coverage depending on circumstances.

ACA’s Medicaid eligibility expansion in Utah

Medicaid was partially expanded in Utah as of April 2019.4 But under the terms of a new waiver that CMS approved in December 2019, the state fully expanded Medicaid as of January 2020 — albeit with a work requirement.5

But the work requirement was suspended as of April 2020, due to the COVID-19 pandemic. And CMS required Utah to remove the work requirement before the waiver could be renewed in 2021.6 So Medicaid is fully expanded in Utah, without a work requirement.

But in 2025, the federal “One Big Beautiful Bill” was enacted, calling for a nationwide work requirement for Medicaid expansion enrollees by January 2027. And Utah is among the states targeting an earlier effective date. State officials submitted a waiver amendment proposal to CMS in July 2025, seeking a Medicaid expansion work requirement with a July 2026 effective date.7

But for the time being, Medicaid expansion coverage is available in Utah with no strings attached. Coverage is available to adults under the age of 65 with household income up to 138% of the federal poverty level (FPL). For a single adult, that’s $21,597 in annual income as of 20258 (the income limit changes each spring, once the state begins to use the latest FPL numbers that are published each year in January). Note that Medicaid eligibility can be determined based on either annual income or current monthly income. This differs from premium subsidy eligibility for private plans, which is always based on total annual income.

As of August 2025, there were nearly 72,000 low-income adults covered under Utah’s Medicaid expansion program. (In Utah’s Medicaid enrollment report, these are broken into four categories, depending on whether they are parents and how old they are.)9

- 332,621 – Number of Utahans covered by Medicaid/CHIP as of October 202510

- 71,802 – Number of Utah residents covered by ACA Medicaid expansion as of August 20259

- 13% – Increase in total Medicaid/CHIP enrollment in Utah since late 201311

Explore our other comprehensive guides to coverage in Utah

The ACA Marketplace allows individuals and families to shop for and enroll in ACA-compliant health insurance plans. Subsidies may be available based on household income to help lower costs.

Hoping to improve your smile? Dental insurance may be a smart addition to your health coverage. Our guide explores dental coverage options in Utah.

Use our guide to learn about Medicare, Medicare Advantage, and Medigap coverage available in Utah as well as the state’s Medicare supplement (Medigap) regulations.

Short-term health plans provide temporary health insurance for consumers who may find themselves without comprehensive coverage.

Frequently asked questions about Utah Medicaid

How do I enroll in Medicaid in Utah?

- You can enroll online through the Utah Medicaid office. You can also use HealthCare.gov and you’ll be routed to the Utah Medicaid office if the preliminary eligibility determination indicates that you’re eligible for Medicaid.

- You can enroll by phone (801) 526-0950 (in Salt Lake County) or toll-free at 1-866-435-7414.

- You can print a paper application (available in English and Spanish) and submit it by mail or fax (addresses and fax number here).

- You can apply in-person at your local Department of Workforce Services office (click here to see a map and find your local office).

How many people were disenrolled from Utah Medicaid after the COVID pandemic?

During the COVID pandemic, from March 2020 through March 2023, states were prohibited from disenrolling anyone from Medicaid. But this rule ended March 31, 2023 and states are once again disenrolling people who are no longer eligible for Medicaid, or who don’t respond to a renewal notification. States had a 12-month “unwinding” period during which they had to initiate eligibility redeterminations for everyone enrolled in the program.

Medicaid disenrollments resumed in May 2023 in Utah, and CHIP premiums began to be assessed starting in mid-2023, after being suspended during the pandemic.l12

223,241 people were disenrolled from Utah Medicaid during the year-long “unwinding” period. In most cases, the disenrollments were due to procedural reasons (meaning the state didn’t have enough information to determine whether they were still eligible).13

Medicaid enrollment in Utah had peaked at about 489,000 people in April 2023. By the end of the unwinding process, in the spring of 2024, it stood at about 340,000.13 It was still at roughly that same level a year later, in mid-2025.14

How does Medicaid provide financial assistance to Medicare beneficiaries in Utah?

Many Medicare beneficiaries receive Medicaid’s help with paying for Medicare premiums, affording prescription drug costs, and covering expenses not covered by Medicare – such as long-term care.

Our guide to financial assistance for Medicare enrollees in Utah includes overviews of these benefits, including Medicare Savings Programs, long-term care coverage, and eligibility guidelines for assistance. Utah’s Medicaid 1115 waiver which was approved in 2019 (described above) provides dental benefits to Medicaid enrollees who are 65 or older.

Does Utah have a Medicaid work requirement?

No, Utah does not have a Medicaid work requirement as of 2025.

But the state is seeking federal approval to implement a work requirement for the Medicaid expansion population starting in mid-2026.7

Utah previously had federal permission for a Medicaid work requirement,5 which was briefly in effect in early 2020 before it was suspended due to the pandemic.

In 2021, CMS renewed Utah’s waiver, but only after the state removed the Medicaid work requirement.6 However, Utah is working to regain federal approval for a work requirement.

The federal “One Big Beautiful Bill,” enacted in 2025, requires states to have work requirements for the Medicaid expansion population by January 2027. Utah is among the states targeting an earlier effective date, and has asked CMS to approve a Medicaid work requirement with a July 2026 start date.7

Medicaid work requirements are controversial, as they ultimately result in people losing coverage no matter what (and most Medicaid enrollees who can work are already doing so). Work requirements in several other states had been overturned or pended due to lawsuits as of early 2020. Michigan and Utah were the only states where Medicaid work requirements were in effect as of early 2020, and both were soon suspended (Michigan’s was overturned by a judge in March) and not reimplemented. However, Georgia has since implemented a work requirement in conjunction with a partial expansion of Medicaid.

Utah Medicaid history and details

Voters approved Utah’s ballot initiative to expand Medicaid, but Republican lawmakers scaled it back

By 2018, Utah was in its fifth year of rejecting federal funding to expand Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act’s guidelines. But during the 2018 legislative session, Utah enacted H.B.472, which directed the state to submit an 1115 waiver proposal to CMS by January 1, 2019, requesting approval for Medicaid expansion in Utah, but only for people earning up to 95% of the federal poverty level (essentially 100%, after the 5% income disregard).

For perspective, the ACA calls for Medicaid expansion to adults with income up to 138% of the poverty level, so Utah lawmakers wanted to only cover part of that population. Their proposed solution did eliminate the coverage gap in the state, but continued to use private plans in the exchange for people with income over the poverty level.

In the waiver amendment that Utah submitted in June 2018 (to partially expand Medicaid), Utah asked the federal government to pay 90% of the cost (under the ACA, this is only available if a state expands Medicaid to individuals earning up to 138% of the poverty level), and allow Utah to impose a work requirement on some Medicaid enrollees. (As discussed below, the Trump administration rejected the state’s request to receive enhanced federal Medicaid funding without a full expansion of Medicaid.)

While lawmakers in Utah were considering a scaled-back version of Medicaid expansion, consumer advocates were working to gather enough signatures to get a Medicaid expansion initiative on the 2018 ballot in Utah. They were successful, and the Utah Medicaid Expansion Initiative passed with more than 53% support in the 2018 election. The Utah Medicaid expansion ballot initiative, which called for Medicaid to be expanded to households with income up to 138% of the poverty level — with no strings attached — garnered support from numerous groups in the state, including AARP Utah and the Utah chapter of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

The text of the ballot initiative called for Medicaid expansion in Utah to take effect as of April 1, 2019, and for Utah to raise the state sales tax by 0.15% (from 4.7% to 4.85%) to fund the state’s portion of the cost of Medicaid expansion.

Utah’s then-Governor, Gary Herbert, said that he would not block Medicaid expansion if the ballot measure passed — which it did — despite his opposition to the ballot initiative (this was in contrast with Maine’s former Governor LePage, who blocked Maine’s voter-approved Medicaid expansion ballot initiative for more than a year; it was eventually implemented when a new governor took over in 2019).

Utah’s limited Medicaid expansion was costing the state more and covering fewer people than full expansion

But just weeks after the 2018 election, GOP lawmakers in Utah intervened to stop the implementation of the Medicaid expansion that voters had approved, opting instead for a version of Medicaid expansion that would cover fewer people and cost the state more, at least in the first few years. S.B.96 was enacted in the 2019 legislative session, reiterating H.B.472’s call for Medicaid expansion only to those with income up to the poverty level.

S.B.96 was enacted in February 2019. The state’s Medicaid expansion ballot initiative had called for expansion to take effect by April 2019, which meant there was very little time to secure federal approval for the modifications the GOP lawmakers wanted to make to Utah’s version of Medicaid expansion.

But since the state already had a pending waiver proposal at CMS with very similar terms to those called for in S.B.96, CMS was able to grant a modified approval of that earlier proposal — albeit at the state’s regular federal funding match rate of about 68%, instead of the 90% federal funding rate that applies in states that have fully expanded Medicaid.

This meant that although the state would cover fewer people under the partial Medicaid expansion program (compared with how many would be covered under full expansion), it would be more expensive for the state.

The approval came in late March, just in time for the state to implement its limited Medicaid expansion on April 1, 2019. Utah residents with income up to the poverty level were able to begin applying for expanded Medicaid at that point.

In addition to partial Medicaid expansion, Utah’s approved waiver also allowed the state to impose a Medicaid work requirement starting in 2020 (this continued to be allowed under the full expansion waiver approval that was granted in late 2019, although the work requirement was suspended due to the COVID pandemic and approval was subsequently withdrawn by the Biden administration).

It was only when Utah fully expanded Medicaid, in January 2020, that the state began to receive the full 90% federal funding match for the Medicaid expansion population.

Utah’s “fallback plan” approved by CMS in December 2019

Although the federal government rejected Utah’s proposal to receive full federal funding for a partial Medicaid expansion, and also rejected the state’s proposal to allow people with income above the poverty level to have a choice between Medicaid and a subsidized plan in the exchange, Utah had already outlined contingency plans earlier in 2019.

The state submitted its “fallback plan” waiver proposal to CMS in November 2019, after accepting public comments earlier in the fall. The fallback plan called for expanding Medicaid eligibility in Utah to households with income up to 138% of the poverty level (ie, what voters approved in the 2018 election), but with a work requirement as well as a lock-out period for “intentional program violations,” premiums for enrollees with income above the poverty level, a ban on presumptive eligibility determinations under Medicaid expansion guidelines, and various other provisions.

CMS granted approval in December 2019, and the new Medicaid eligibility guidelines took effect in January 2020. The work requirement provision of the waiver proposal was approved and took effect in 2020, but it was suspended by April due to the COVID pandemic, and approval for it was later withdrawn by the Biden administration.

Utah had a contingency plan in case its work requirement was rejected. In that case, Utah’s final plan, if no waiver approval had been granted by July 1, 2020, was to simply implement Medicaid expansion as called for in the ACA (and in the state’s ballot initiative), without a waiver.

The state had created an at-a-glance chart that compared the details of the bridge plan, the per capita cap plan, the fallback plan and the regular expansion plan. The Utah Department of Health has also published a chart showing enrollment over time in both the partial expansion and the full expansion program.

Louise Norris is an individual health insurance broker who has been writing about health insurance and health reform since 2006. She has written dozens of opinions and educational pieces about the Affordable Care Act for healthinsurance.org.

Looking for more information about other options in your state?

Need help navigating health insurance options in Utah?

Explore more resources for options in UT including ACA coverage, short-term health insurance, dental and Medicare.

Speak to a sales agent at a licensed insurance agency.

Footnotes

- ”Medicaid, Children’s Health Insurance Program, & Basic Health Program Eligibility Levels” Medicaid.gov. Accessed Sep. 28, 2025 ⤶

- ”With respect to MAGI conversion, how will the 5% disregard be applied?” Medicaid.gov. Accessed Sep. 28, 2025 ⤶

- ”12 Month Post-partum Conversion” Utah Department of Health & Human Services. Accessed Sep. 28, 2025 ⤶

- ”Medicaid Expansion: What’s Next for Utah?” Utah Senate. Accessed Sep. 28, 2025 ⤶

- ”CMS approval of amendments to Utah’s “Primary Care Network” (PCN) Section 1115 demonstration” Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Dec. 16, 2020 ⤶ ⤶

- ”State of Utah, Section 1115 Demonstration Amendment, Community Engagement” Utah Department of Health & Human Services. Accessed Sep. 28, 2025 ⤶ ⤶

- ”Utah’s Medicaid Reform 1115 Demonstration Amendment Request” Utah Department of Health & Human Services. July 3, 2025 ⤶ ⤶ ⤶

- ”2025 Poverty Guidelines” U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Accessed Sep. 28, 2025 ⤶

- ”Updated Medicaid August 2025 Enrollment Report” Utah Department of Health & Human Services. Data for August 2025. Accessed Sep. 28, 2025 ⤶ ⤶

- “October2025 Medicaid & CHIP Enrollment Data Highlights”, Medicaid.gov, Accessed February 2026 ⤶

- “Total Monthly Medicaid & CHIP Enrollment and Pre-ACA Enrollment”, KFF.org, Accessed February 2026 ⤶

- Unwinding Medicaid Eligibility. Utah Department of Health and Human Services. September 2023. ⤶

- Medicaid Enrollment and Unwinding Tracker. KFF. Accessed Sep. 28, 2025 ⤶ ⤶

- “June 2025 Medicaid & CHIP Enrollment Data Highlights”, Medicaid.gov, Accessed Sep. 28, 2025 ⤶