Medicaid eligibility and enrollment in Virginia

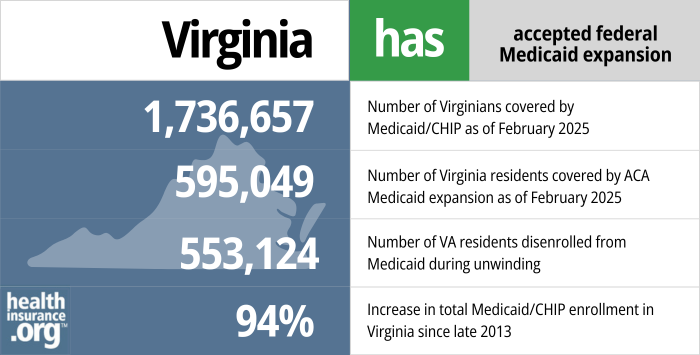

Virginia expanded Medicaid in 2019, and 595,000 people were enrolled in Virginia’s expanded Medicaid as of early 2025

Who is eligible for Medicaid in Virginia?

In addition to low-income elderly residents and those who are disabled, Medicaid is available to the following populations in Virginia:1

- Pregnant people with household incomes up to 148% of poverty (this coverage also continues for 12 months postpartum; Virginia was one of the first states to extend postpartum coverage to 12 months2). Virginia also offers FAMIS — Family Access to Medical Insurance Security3 — which provides health coverage for uninsured pregnant women who are not eligible for Medicaid, but who have household incomes up to 205% of poverty. FAMIS is Virginia’s CHIP.

- Adults under age 65 are eligible if their income doesn’t exceed 138% of the poverty level (this is due to Medicaid expansion, which took effect in Virginia in 2019).

- Children are eligible for Medicaid for Children (called FAMIS Plus) if their household incomes are up to 148% of poverty. Above that level, they are eligible for the FAMIS program if household income doesn’t exceed 205% of the poverty level.

Apply for Medicaid in Virginia

Enroll online at Cover Virginia or by phone at 1-855-242-8282. Mail a paper application to your local Department of Social Services office or apply in person at a Department of Social Services office.

Eligibility: The aged, blind, and disabled. Adults under age 65 are eligible with household incomes up to 138% of FPL. Pregnant women are eligible with household incomes up to 143% of FPL. Children are eligible for Medicaid or CHIP with household incomes up to 200% of FPL.

Medicaid expansion in Virginia

Medicaid expansion in Virginia took effect in January 2019. Enrollment under the expanded eligibility guidelines began November 1, 2018, for coverage that took effect January 1, 2019. As of February 2025, more than 595,000 people were covered under Virginia’s Medicaid expansion guidelines (out of more than 1.7 million Medicaid enrollees in the state).4

Virginia enacted a budget bill in May 20185 that called for the expansion of Medicaid starting in January 2019, albeit with a work requirement that was expected to take effect at some point in the future, after approval by the federal government. (As described below, the state paused the process of implementing a work requirement in late 2019, and officially withdrew the proposal in mid-2020.) After pushing for Medicaid expansion since taking office, Gov. Northam hailed the budget as a victory when he signed it into law.6

As a result of eligibility expansion, Medicaid is available to Virginia adults under age 65 who earn up to 138% of the federal poverty level. In 2024, that’s $20,782 for a single person, and about $35,631 for an adult in a household of three people).

- 1,736,657– Number of Virginians covered by Medicaid/CHIP as of Feb. 20254

- 595,049 – Number of Virginia residents covered by ACA Medicaid expansion as of Feb. 20254

- 553,124 – Number of VA residents disenrolled from Medicaid during post-pandemic unwinding7

- 94% – Increase in total Medicaid/CHIP enrollment in Virginia since late 20138

Explore our other comprehensive guides to coverage in Virginia

We’ve created this guide to help you understand the Virginia health insurance options available to you and your family, and to help you select the coverage that will best fit your needs and budget.

Hoping to improve your smile? Dental insurance may be a smart addition to your health coverage. Our guide explores dental coverage options in Virginia.

Use our guide to learn about Medicare, Medicare Advantage, and Medigap coverage available in Virginia as well as the state’s Medicare supplement (Medigap) regulations.

Short-term health plans provide temporary health insurance for consumers who may find themselves without comprehensive coverage.

Frequently asked questions about Virginia Medicaid

How do I enroll in Medicaid in Virginia?

There are a variety of ways to enroll in Medicaid in Virginia. You can:

- Fill out the online application at www.commonhelp.virginia.gov (you can begin this process at the Virginia Insurance Marketplace if you aren’t sure whether you’ll be eligible for Medicaid or for a subsidized private plan)

- Apply over the phone by calling the Cover Virginia Call Center at 1-855-242-8282 (TDD: 1-888-221-1590). Help is available Monday to Friday, 8:00 am to 7:00 pm and Saturday, 9:00 am to 12:00 pm.

- Complete a paper application (English version; Spanish version) and mail it in or drop it off at your local Department of Social Services Office.

- If you also want to apply for other benefits, you can call the Virginia Department of Social Services Enterprise Call Center at 1-855-635-4370.

How does Medicaid provide assistance to Medicare beneficiaries in Virginia?

Many Medicare beneficiaries also receive help through Medicaid. This can include assistance with Medicare premiums, programs that lower prescription drug costs, and long-term care services.

Our guide to financial assistance for Medicare beneficiaries in Virginia explains programs that can provide assistance, including Medicare Savings Programs, long-term care benefits, and Extra Help.

How many Virginia residents were disenrolled from Medicaid after the pandemic?

From March 2020 through March 2023, states received additional Medicaid funding due to the COVID pandemic, but on the condition that they could not disenroll anyone from Medicaid during that time. That rule ended March 31, 2023, and states began a year-long “unwinding” process of redetermining eligibility for everyone enrolled in Medicaid. Those who were no longer eligible (or who failed to respond to a renewal notice) were disenrolled from Medicaid.

553,124 people were disenrolled from Virginia Medicaid during the unwinding period, while coverage was renewed for more than 1.5 million enrollees.9

Just over half of the people disenrolled from Virginia Medicaid were disenrolled for procedural reasons, meaning the state didn’t have enough information on file to determine whether they were still eligible. Nationwide, 69% of disenrollments were for procedural reasons.10

Virginia had estimated that about 300,000 residents would lose Medicaid during the “unwinding” of the pandemic-era continuous coverage rules.11 The total far surpassed initial projections, as was the case in most states.

Those who are no longer eligible for Medicaid could transition to other coverage. Depending on the person’s circumstances, this could be an employer’s plan, Medicare, or a plan purchased through the Virginia Insurance Marketplace.

34,110 Virginia residents transitioned from Medicaid to a Marketplace plan during the unwinding process12 (Virginia used HealthCare.gov for the initial months of the unwinding process, but switched to a state-run platform at the start of 2024).

Virginia Medicaid History and Details

Virginia Medicaid expansion history

Former Virginia Governor, Terry McAuliffe took office in January 2014, and had long said that Medicaid expansion was one of his top priorities. It was a contentious issue between the Governor and the state legislature, with a government shutdown that loomed in the summer of 2014 because of budget disagreements pertaining to Medicaid expansion.

Various proposals to partially expand Medicaid, or expand coverage with modifications, were considered by lawmakers in 2014, 2015, and 2016, but none of them passed. In September 2016, Governor McAuliffe reiterated his point that Medicaid expansion would help to close the budget gap that Virginia was facing. McAuliffe left office in January 2018, with Medicaid expansion still on his wish list. But his successor, Governor Ralph Northam, had campaigned on the promise of expansion, and Virginia Democrats gained significant ground in the House of Delegates. But a tie-breaker win went to the Republicans, who held a 51-49 majority in 2018.

Gov. Northam began pushing for Medicaid expansion as soon as he took office, building on the work that McCauliffe had done. Several days before lawmakers passed the budget with Medicaid expansion included (in May 2018), Northam had vetoed bills that would have expanded access to association health plans, lengthened short-term health insurance plans, and expanded eligibility for catastrophic health plans. In his statements regarding the vetoes, Northam noted repeatedly that the best thing Virginia could do to stabilize the insurance market and make coverage available to more people would be to expand Medicaid.

Legislation (SB 572) was introduced in the Virginia Senate in January 2018 to expand Medicaid (albeit with work requirements and premiums), but a party-line vote in the Education and Health Committee killed it before the end of January. The following week, a House committee voted 14-3 in favor of HB 338, which would have imposed work requirements on some existing Medicaid enrollees in Virginia. HB338 passed in the house in February, with a 64 to 36 vote, but it did not advance in the Senate.

Former Governor McAuliffe’s proposed budget was under review in the 2018 legislative session, and it called for Medicaid expansion – as had McAuliffe’s proposed budgets for the three previous years. In the House, two budget bills – HB29 and HB30 – were considered, and both included Medicaid expansion (HB29 was a short-term budget bill, covering the first half of 2018; HB30 was a two-year budget bill, starting where HB29 ended).

Both budget bills passed by a wide margin in the House, with bipartisan support. So the Virginia House of Delegates essentially voted in support of Medicaid expansion three times during the 2018 session, passing HB338, HB29, and HB30 (although HB338 was based on the premise that the state would seek permission from the federal government to impose a work requirement as a condition of Medicaid expansion). 2018 was the first time that the Virginia House had voted in favor of Medicaid expansion — due in large part to the gains that Democrats made in the 2017 election, and the fact that Virginia voters clearly supported Medicaid expansion.

The Senate, however, continued to steadfastly reject Medicaid expansion, and the result was an impasse on the budget. The regular legislative session ended in March with no budget agreement, and considerable tensions between the House and Senate on the issue of Medicaid expansion. Gov. Northam called lawmakers back for a special session that began on April 11, to continue to work on the budget. Lawmakers had to have a budget in place by July 1 in order to avoid a government shutdown. Governor Northam proposed a new budget, which was under consideration during the special session via HB5001 and HB5002.

The House Appropriations Committee approved the new budget on April 13, with an enhanced work requirement, designed to get Republicans in the Senate to support the measure (at least two Senate Republicans had to vote yes on a budget with Medicaid expansion in order to pass it; ultimately, four Senate Republicans supported the measure). The new budget bill stipulated that the work requirement would be an enforced condition of continued enrollment in Medicaid. But ultimately, Medicaid expansion took effect in January 2019, and the work requirement never took effect (more details below). The work requirement proposal was subsequently withdrawn by the state.

An estimated 400,000 people were expected to become eligible for coverage under the expanded guidelines, but that was pre-COVID. The number of people covered under Medicaid expansion was much higher during the pandemic. By early 2020, about 375,000 people had gained coverage under the expanded eligibility guidelines. By April 2023, however, that number had grown to more than 735,000 people.13

Post-pandemic eligibility redeterminations resumed at that point, and enrollment in Virginia’s Medicaid expansion had dropped to 595,000 people by early 2025.4

Before 2019, about 138,000 Virginians had been in the coverage gap, not eligible for Medicaid in Virginia, and also not eligible for premium subsidies because their income was too low (i.e., under the poverty level). The expansion of Medicaid made coverage realistically available to this group. And people with income between 100% and 138% of the poverty level, who were previously eligible for significant premium subsidies and cost-sharing reductions in the exchange, became eligible for Medicaid instead as of 2019, with lower out-of-pocket costs.

According to Medicaid expansion advocates, Virginia had been missing out on $142 million in federal funding every month since the start of 2014, as a result of not expanding Medicaid. But that changed in 2019, when federal Medicaid expansion funding started to flow into the state. States pay 10% of the cost of Medicaid expansion, and the federal government pays 90%. This is a much more generous split than regular (non-expansion) Medicaid funding.

COMPASS waiver proposal was officially withdrawn by Gov. Northam in 2020

Virginia unveiled its waiver proposal for the Medicaid work requirement, premiums, and cost-sharing in September 2018. After a public comment period and public meetings, the final waiver proposal (called COMPASS) was submitted to CMS in November 2018. In early December 2019, a few weeks after Democrats swept the election in Virginia (they controlled both the House and Senate as of 2020), Virginia’s Medicaid Director notified CMS that the state was formally delaying the negotiations for the work requirement. And during the budget approval process in the 2020 legislative session, lawmakers eliminated the COMPASS requirements (work requirement, premiums, etc.), paving the way for Gov. Northam to officially withdraw the work requirement proposal in July 2020.

GOP lawmakers were already frustrated by the fact that although Medicaid expansion took effect in January 2019, it had appeared that it could be a year or two later before a work requirement took effect, just due to the protracted process of getting a waiver approved by the federal government. So it was not surprising that the decision to pause the negotiations over the work requirement was not well received by Republicans in Virginia’s legislature, who expressed dismay that what they had considered an ironclad promise had been broken.

But work requirements in Arkansas, Kentucky, and New Hampshire had already been overturned by the courts. Indiana paused their work requirement due to a lawsuit. And Arizona indefinitely postponed their work requirement due to the court cases in other states. By early 2020, there were work requirements in effect in just two states — Michigan and Utah. And within a few months, both had been suspended (Michigan’s was overturned by a judge, and Utah’s was suspended due to the COVID-19 pandemic).

Medicaid work requirements tend to seem like “common sense” to people who aren’t well-versed in public health, and they have certainly gained significant support among GOP lawmakers in various states. But most people who receive Medicaid, including those eligible under Medicaid expansion, are already working, in school, caring for children or disabled family members, or unable to work for a variety of reasons (disability, mental or physical illness, etc.). And there is no getting around the fact that Medicaid work requirements (and the associated reporting requirements) cause people to lose coverage. They are also expensive for the state to administer. Taking all of that into consideration, the state opted to skip the Medicaid work requirement, and just proceed with Medicaid expansion as called for in the ACA.

Medicaid work requirements are gaining traction again, however, during the second Trump administration. And Congressional lawmakers are considering the possibility of nationwide work requirements for some Medicaid populations.14

Virginia Medicaid history

Medicaid became effective in Virginia in July 1969, making it one of the last states in the country to implement the program (the first states to provide Medicaid did so in January 1966; note that Virginia was also five years behind many other states in implementing Medicaid expansion under the ACA).

In late 1991, CMS approved Virginia’s Medicaid waiver application to begin a Medicaid primary care case management program dubbed MEDALLION. The case management system was a response to escalating costs, increasing use of emergency rooms in lieu of primary care, and physician reluctance to treat Medicaid patients. The managed care model began as a pilot program in five counties, but was considered a success and expanded statewide in 1995. Virginia was also one of the first states to expand the managed care program to include elderly, blind, and disabled Medicaid recipients (these populations had typically always been covered by traditional Medicaid in each state, rather than managed care).

By 1995, in select areas of the state, Virginia Medicaid recipients were able to choose from among a variety of Managed Care Organizations (MCOs) under the Options Program. This was the first time MCOs were used in the Medicaid program in Virginia.

The Medallion II MCO took effect in 1996, and it was gradually expanded across the state. By 2001, there were seven MCO partners in the Medallion II program. In the ensuing years, there have been numerous consolidations, entries, and exits on the part of MCOs. Overall, the state has concluded that MCOs are the most cost-effective way to provide Medicaid benefits to eligible residents, and 82% of the state’s Medicaid population was enrolled in MCOs as of 201.

Virginia created FAMIS (Family Access to Medical Insurance Security) in 2000, following the creation of CHIP (Children’s Health Insurance Program) by the federal government in 1997. FAMIS-eligible families can choose to enroll in available employer-sponsored insurance and receive help with the premiums if that is deemed more cost-effective than directly providing coverage through the FAMIS program.

The state also took advantage of the fact that the ACA allows Medicaid to cover inpatient care for prison inmates, instead of having the Department of Corrections foot the bill. Virginia started doing this in 2014, and it’s estimated to have saved the state about $1 million in just the first year, because Medicaid expenses are split with the federal government, while DOC expenses are covered by the state

Louise Norris is an individual health insurance broker who has been writing about health insurance and health reform since 2006. She has written dozens of opinions and educational pieces about the Affordable Care Act for healthinsurance.org.

Looking for more information about other options in your state?

Need help navigating health insurance options in Virginia?

Explore more resources for options in Virginia including ACA coverage, short-term health insurance, dental insurance and Medicare.

Speak to a sales agent at a licensed insurance agency.

Footnotes

- ”Am I Eligible?” Virginia Department of Medical Assistance Services. Accessed Feb. 18, 2025 ⤶

- ”Virginia Medicaid Announces 12-Month Postpartum Coverage” Virginia Department of Medical Assistance Services. Nov. 18, 2021 ⤶

- ”FAMIS” Virginia Department of Medical Assistance Services. Accessed Feb. 18, 2025 ⤶

- “Enrollment Reports (February 2025)” Virginia Department of Medical Assistance Services. Accessed Feb. 18, 2025 ⤶ ⤶ ⤶ ⤶

- ”Virginia HB5002” and “Virginia HB5001” BillTrack50. Enacted May 2018 ⤶

- ”Governor Northam Statement on Biennial Budget that Expands Health Care and Invests in a Stronger Economy” Former Virginia Governor Ralph Northam. May 30, 2018 ⤶

- ”Eligibility Redetermination Tracker“, DMAS.virginia.gov, Accessed January 2025 ⤶

- “Total Monthly Medicaid & CHIP Enrollment and Pre-ACA Enrollment”, KFF.org, Accessed January 2025 ⤶

- ”Medicaid Enrollment and Unwinding Tracker” KFF.org. Jan. 31, 2025 ⤶

- ”Medicaid Enrollment and Unwinding Tracker” KFF.org. Jan. 31, 2025 ⤶

- ”Virginia’s looming Medicaid cliff” Axios. Apr. 4, 2023 ⤶

- ”HealthCare.gov Marketplace Medicaid Unwinding Report” and “State-based Marketplace (SBM) Medicaid Unwinding Report” Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Accessed Feb. 18, 2025 ⤶

- ”Enrollment Reports” Virginia Department of Medical Assistance Services. Accessed May 22, 2024 ⤶

- ”5 Key Facts About Medicaid Work Requirements” KFF.org. Feb. 18, 2025 ⤶