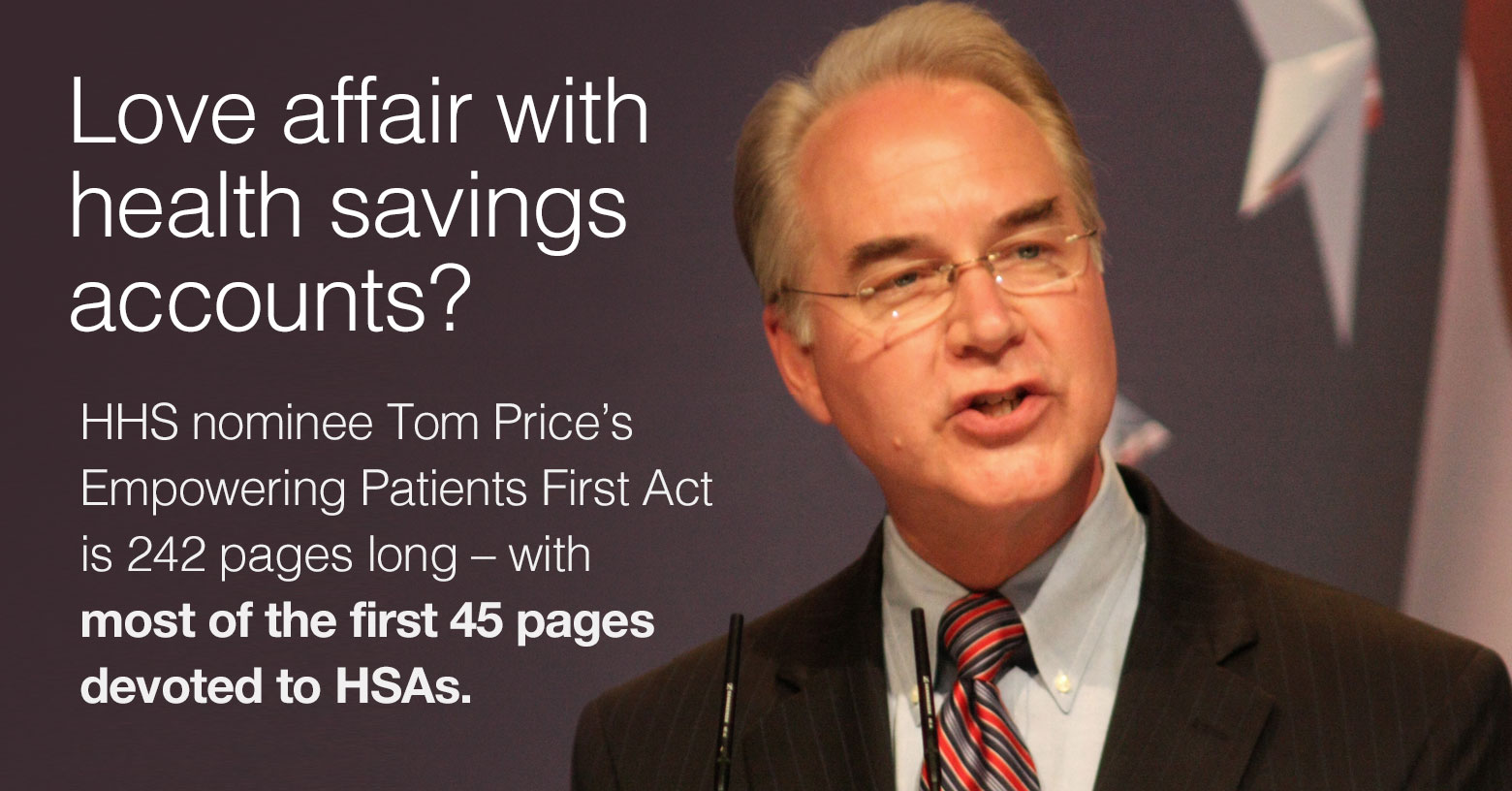

President-elect Donald Trump has named Rep. Tom Price (R-Ga.) to be the next Secretary of Health and Human Services. Assuming he's confirmed by the Senate, Price will be a powerful figure in the future of healthcare reform, helping to shape the Trump Administration's approach to where we go from here. And we can be fairly certain that it's going to include a lot more focus on health savings accounts (HSAs).

Since 2009, Rep. Price has been promoting his Empowering Patients First Act. The most recent version, H.R. 2300, was introduced in 2015. The bill is 242 pages long, and most of the first 45 pages are devoted to HSAs. They also figure prominently into most of the other Republican health care reform proposals, although the idea is that they'd work in unison with numerous other provisions; none of the proposals call for HSAs to be the only major tenet of reform.

Why the GOP loves HSAs

HSAs fit nicely into the GOP health care reform narrative: Ostensibly, high-deductible health plans (HDHPs) and HSAs encourage patients to be active shoppers, seeking out the best value in care, and thus lowering overall costs via free-market mechanisms. (In reality, this is much harder than it sounds, and price transparency is still woefully lacking in most states.)

High-deductible health plans also curb overutilization of healthcare, since enrollees are less likely to seek non-essential care when they have to pay the whole bill themselves, as opposed to just a copay. (Before the deductible is met, HDHPs only pay for preventive care.) Less utilization does result in lower overall healthcare costs, but critics note that patients are also less likely to seek out necessary care when covered by high-deductible health plans, which can lead to higher costs and worse outcomes in the long run.

HDHPs/HSAs also put a certain amount of onus on individuals to dutifully save a portion of their income to cover their future medical expenses. In other words, they exemplify the personal responsibility factor that GOP health care reform advocates tend to favor. Similar grandiose notions of personal responsibility show up in Republican talking points against expanding Medicaid, when they cry foul over the idea of giving able-bodied low-income people access to government funded health coverage.

And as >Wendell Potter explains, HSA-qualified plans (and in general, most plans with high deductibles) also tend to be more profitable for insurers. In turn, that makes them more popular among politicians who are on the receiving end of insurance industry lobbying.

Do people like HSAs?

HDHPs and HSAs have become increasingly popular with employers and health plan enrollees over the last decade. The Kaiser Family Foundation’s annual employer health benefits survey found that 29 percent of workers with employer-sponsored health benefits were enrolled in HSA-qualified plans in 2016, up from just 4 percent in 2006.

The growing popularity of HSA-qualified plans might reflect genuine enthusiasm for HSAs. But it could also be related to the fact that healthy individuals tend to gravitate to lower-priced health plans with higher out-of-pocket exposure, and HSA-qualified plans tend to be among the least expensive options that employers offer.

By mid-2016, there were more than 18 million HSAs, holding more than $34.7 billion in assets. But it’s worth noting that many HDHP enrollees don’t establish an HSA at all, either because they don’t understand how the HSA works, or because they don’t have any extra money to put in the account.

How HSAs work

High-deductible health plans and HSAs are already well entrenched in our health insurance system. So let's take a look at how HSAs currently work:

- If you have an HSA-qualified high-deductible health plan, you – or your employer – can contribute money to the account, up to the maximum allowed each year under IRS regulations. HSA contributions are exempt from federal taxes, and in most states, the contributions are also exempt from state taxes.

- The money in the HSA can be withdrawn at any time to pay for qualified medical expenses (even years down the road, and even if you're no longer covered by an HDHP at that point). There are no taxes or penalties for withdrawals as long as the money is used for qualified medical expenses.

- If the HSA generates investment gains, the gains are tax-free. If the money is not needed for medical expenses, it rolls over from one year to the next, and continues to grow.

- Once you reach age 65, the money in the HSA can be withdrawn for purposes other than qualified medical expenses, subject to income tax at that point (essentially, just like a Traditional IRA). Withdrawals that aren't used for qualified medical expenses prior to age 65 are subject to income tax plus a 20 percent penalty. But the penalty does not apply after you're 65. You can also choose to keep the money in the HSA and use it for potential future medical needs, such as long-term care – in that case, it wouldn't be subject to taxation at all.

In short, HSAs under current regulations are extremely tax advantaged: The money goes in tax-free, grows tax-free, and comes out tax-free, as long as it's used for medical expenses. And HSA-qualified HDHPs are widely available, as they continue to work well with the ACA's regulations.

How Price's legislation would enhance HSAs

Whatever health care reform legislation is introduced in 2017 is likely to be a combination of various proposals Republican lawmakers have put forth over the last few years. But let's take a look at how Price's Empowering Patients First Act would enhance HSAs:

- H.R. 2300 calls for a refundable tax credit to help people pay for health insurance (if that sounds familiar, it's because the ACA's premium subsidies are also refundable tax credits; but the credits would be structured much differently under H.R.2300). If the enrollee picks a health plan with premiums that are less than the tax credit amount, the excess tax credit could be deposited into the enrollee's HSA (if the enrollee doesn't have an HSA, any tax credit in excess of the enrollee's premium would revert to the government). This provision encourages people to a) select HSA-qualified plans and establish HSAs, and b) enroll in plans with low premiums, since they'd be able to keep the excess tax credit in their HSAs.

- The bill would provide a $1,000 one-time HSA contribution from the government, to incentivize people to opt for HSA-qualified plans and establish HSAs.

- The maximum HSA contribution limits would be increased to equal the contribution limits that apply to IRAs, and spouses who are both 55 or older would be allowed to make catch-up contributions to the same IRA (under current rules, each spouse has to make catch-up contributions to his or her own HSA, even if they have family coverage under an HDHP and make their normal contributions to just one HSA).

HSAs would become more widely available:

- High-risk pools funded by H.R. 2300 would have to include at least one HSA-qualified plan option.

- Coverage under a health care sharing ministry would enable an individual to establish and contribute to an HSA.

- Seniors enrolled in only Medicare Part A would be able to continue to contribute to an HSA.

- Native Americans would be able to contribute to an HSA even if they get care from IHS.

- People receiving VA benefits, and those eligible for TRICARE Extra or TRICARE Standard would still be able to contribute to an HSA.

HSAs would become even more tax advantaged:

- They'd be inheritable by the account owner's surviving spouse, child, parent, or grandparent, retaining HSA status (under current rules, only a surviving spouse can inherit HSAs without triggering taxes).

- Required minimum distributions from IRAs could be transferred to an HSA without being included in gross income for the year. The point of required minimum distributions it to ensure that the government eventually gets to assess taxes on IRA funds; if the money can be transferred into an HSA instead, it's a significant tax shelter. And it goes without saying that this would benefit higher-income folks, since lower-income retirees would presumably need the money from their IRA for living expenses, and wouldn't be able to just transfer it into another savings vehicle.

HSA funds could be used for additional expenses:

-

- People would be allowed to open an HSA by April 15 and use it to cover expenses that were incurred the prior year.

Direct Primary Care arrangements and concierge medicine fees could be paid with HSA funds.

HSAs: Great for some, but not a universal solution

To be clear, I am not at all opposed to HSAs. But I do question their utility as a pillar of health care reform. Our family has had an HSA since 2006, and our high-deductible health plan fits well with our goal of keeping our premiums as low as possible. We've also been very fortunate in terms of not needing to use our health insurance over the years, so our out-of-pocket costs have been minimal.

But about 40 percent of Americans in their 40s have a pre-existing condition, and the percentage gets higher as people get older; a significant number of people do need to use their health insurance each year, and would need to have funds in their HSA to cover those costs.

Yet nearly half of Americans don't have enough money to cover a $400 emergency. To imagine that HSA-centric legislation is going to create a seismic shift in Americans' ability and willingness to save money is ivory-tower thinking, especially if it's not combined with measures to ensure that everyone can earn a living wage.

While additional incentives in the tax structure might encourage more people to save more money for medical expenses, the reality is that those would probably be mostly the same people who are already willing and able to save for medical expenses under our current system.

Expanding and enhancing HSAs would absolutely benefit higher-income Americans who are looking for additional ways to shield their money from taxes. And it might also encourage more middle-income households to save for future medical expenses.

But as a healthcare reform strategy, relying heavily on stockpiled personal assets seems like a recipe for failure, particularly given the fact that so many Americans already struggle with finances, and given the fact that low-income people tend to be disproportionately represented among the population most in need of assistance with their health insurance.

Louise Norris is an individual health insurance broker who has been writing about health insurance and health reform since 2006. She has written hundreds of opinions and educational pieces about the Affordable Care Act for healthinsurance.org.