EDIT: The following FAQ explains how the COVID relief in the CARES Act affected eligibility for premium subsidies and Medicaid, and how premium subsidy reconciliation on tax returns would have worked under normal rules. However, the American Rescue Plan, which was enacted in March 2021, provides significant relief. It ensured that nobody had to repay excess premium subsidies from 2020, regardless of why they would otherwise have owed the IRS some or all of the premium subsidy that was paid on their behalf in 2020. And it also ensured that people who received unemployment compensation in 2021 were eligible for significant subsidies that made it possible to enroll in robust health coverage for 2021.

Those provisions have since expired, however. The excess subsidy repayment amnesty was for 2020 only, and the unemployment-based subsidies were for 2021 only. But as of 2022, the American Rescue Plan’s other subsidy enhancements are still in effect, which means the “subsidy cliff” is still eliminated and people still pay a smaller percentage of their income for health insurance. Unless Congress takes action to extend these provisions, they will expire at the end of 2022, and the rules will revert to normal as of 2023.

Q. How could COVID-19 financial relief affect my income taxes for 2020?

A. The COVID-19 pandemic has caused widespread economic distress across the United States, with the stress of job loss compounded in many cases by the loss of employer-sponsored health coverage.

The American Rescue Plan Act includes a one-time provision that will rescue marketplace plan buyers from repayment of thousands of dollars in excess insurance premium subsidies for the 2020 tax year. | Image: onephoto / stock.adobe.com

Fortunately, the CARES Act and subsequent government regulations have provided many Americans with additional unemployment benefits that would not normally have been available. And the Affordable Care Act ensured that Americans losing their health insurance coverage would be able to transition to an individual-market health plan, regardless of their medical history.

It also made Medicaid available – in most states – to people whose monthly income fell to no more than 138% of the federal poverty level. (For a single person, that was about $1,467 in monthly income in 2020.)

But there are still 13 states where there’s a coverage gap for people who earn less than the poverty level, due to those states’ refusal to accept federal funding to expand Medicaid. And there are pitfalls that go along with premium subsidies for individual-market health coverage – some of which people might not fully understand until they file their 2020 taxes in early 2021, and some of which are related to the benefits provided by the CARES Act.

The basics of COVID-19 financial relief

First, the basics of the financial assistance and how it’s counted in terms of your income:

- The CARES Act provided an extra $600 a week in federal unemployment benefits through the end of July 2020, in addition to regular unemployment benefits (the additional unemployment benefits have since been reduced to $300/week, but have been extended twice, most recently through September 6, 2021).

- An additional $300 a week in temporary Lost Wage Assistance (via FEMA) was made available after the extra federal unemployment benefits expired, although the availability of this benefit has varied from one state to another.

- In normal circumstances, unemployment benefits are simply treated as taxable income and are counted when determining ACA-specific modified adjusted gross income for Medicaid/CHIP eligibility as well as subsidy eligibility in the exchange. But these are not normal circumstances.

- The extra federal benefits (both the temporary unemployment benefits and the temporary Lost Wage Assistance) are NOT counted when MAGI-based Medicaid/CHIP eligibility is determined.

- The extra federal benefits ARE counted as part of your total taxable income however, which means they do count when determining eligibility for premium subsidies and cost-sharing reductions.

- For 2021 only, people receiving unemployment compensation are eligible for $0 premium Silver plans with robust cost-sharing reductions. This benefit, which is part of the American Rescue Plan, does not apply to people who are otherwise eligible for Medicaid or an employer-sponsored plan that’s considered affordable and provides minimum value.

- The CARES Act also provided a one-time $1,200 payment to many Americans, depending on income. A second stimulus bill, enacted in late 2020, provided an additional $600, and the American Rescue Plan, enacted in March 2021, provided an additional $1,400. These stimulus checks not taxable and are not counted as income for any purposes.

COVID-19 financial relief and your income taxes for 2020

EDIT: As noted above, the American Rescue Plan has provided relief from excess premium tax credit repayments for 2020. This is a one-time provision; excess premium tax credits for 2021 will still have to be repaid to the IRS (but they won’t be as common or as large, especially since the “subsidy cliff” has been eliminated for 2021 and 2022). The following is how the situation would have worked, had the ARP not been enacted.

So what does all of that mean in terms of the 2020 tax return that you’ll be filing next spring? It will depend on your specific income, but some people who received advance premium tax credits (APTC) to offset the cost of health coverage in 2020 might end up having to repay some or all of that money to the IRS when they file their 2020 taxes.

Dave Keller, President of INSXCloud, Inc., is appealing to Congress to change the rules so that the additional COVID-related federal unemployment benefits would not be counted as part of a person’s ACA-specific MAGI. Keller notes that “while the APTC has enabled many people to enroll in an ACA plan at little or no cost to them, they may be staring at a large tax consequence when they file their 2020 taxes next year, at a time that they can least afford it.”

If Congress moved to exempt that federal relief, it would remove a potential tax burden for Americans already facing financial strain during this pandemic.

Will the COVID-related financial assistance affect my 2020 health insurance subsidy?

The American Rescue Plan provides significant relief to marketplace enrollees who would have had to repay some or all of their premium tax credit for 2020. But here’s what people were needing to consider in 2020 in terms of the interaction between health coverage and the COVID relief measures:

- If you were eligible for Medicaid at some point in 2020 based on your monthly income, that will not have any effect on your 2020 tax return. Medicaid does not get reconciled with the IRS.

- If you are in one of the 13 states where there’s still a coverage gap (plus Nebraska prior to October 2020, when there was still a coverage gap there), the additional federal unemployment benefits might have been enough to push your total projected income above the poverty level, making you eligible for premium subsidies in the exchange. Even if your income ultimately ends up below the poverty level when all is said and done, you won’t have to repay the APTC that was paid on your behalf when you file your taxes.

- But on the higher end of the scale, if the additional federal benefits push your total ACA-specific MAGI higher than you originally projected but not above 400% of the poverty level, you’ll have to pay back some or all of the APTC, although there are caps that apply to the repayment amounts in that case. (Thanks to the American Rescue Plan, excess premium subsidies from 2020 do not have to be repaid to the IRS.)

- And unfortunately, if the additional federal benefits push your MAGI for 2020 above 400% of the poverty level, you will have to repay all of the APTC that was paid on your behalf this year. (Again, this does not apply for 2020, thanks to the ARP.)

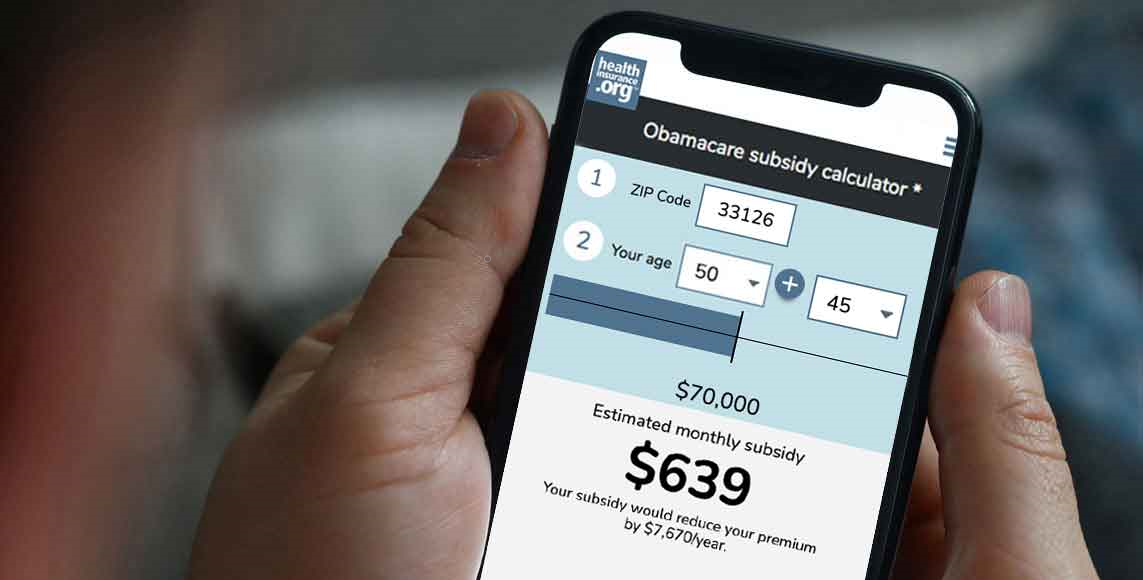

This last point was the most pressing concern, as it can amount to thousands of dollars being owed to the IRS, depending on where you live, how old you are, and how many months APTC was paid on your behalf for a plan purchased in the exchange (APTC is larger in areas where coverage is more expensive, and it’s larger for older people since their pre-subsidy premiums are higher). Fortunately, excess APTC of any amount does not have to be repaid to the IRS for the 2020 tax year.

People are often caught off guard by the fact that the APTC reconciliation process uses the entire year’s income — not just income during the time you were enrolled in a plan through the exchange. So it’s not just the enhanced federal unemployment benefits and Lost Wage Assistance benefits that could cause a snag here; it’s also income that a person earns later in the year, after having a plan through the exchange for only part of the year. (Although this is no longer an issue for 2020, it is still a factor that enrollees need to be aware of in future years.)

What can I do to avoid a surprise at tax time?

If you’re facing the possibility of having to repay some or all of your APTC, there are a few things to keep in mind:

- Contributions to pre-tax retirement accounts and health savings accounts will reduce your ACA-specific MAGI.

- In order to contribute to a health savings account (HSA), you need to have an HSA-qualified high-deductible health plan (HDHP).

- You can make the full year’s contribution to an HSA even if you only have HSA-qualified coverage in place during the last month of the year, as long as you then continue to maintain HSA-qualified coverage for all of the following year.

- If you’re returning to full-time work and are eligible to participate in your employer’s health plan, you might want to check to see whether they offer an HDHP and whether it would be worth your while to enroll in it and contribute to the HSA. (Definitely check with a financial advisor to see if this is the best overall strategy, as it’s a decision that should only be made with your full financial situation in mind.)

- If you’re still enrolled in a plan through the exchange and are realizing that you’re going to have to repay your APTC because your total MAGI is going to be higher than you had projected, you can contact the exchange and have them adjust your APTC so that it’s no longer paid for the final months of the year. This will reduce the amount you’ll have to repay to the IRS, but that also means you’ll have to pay full price for your health coverage for the final months of the year, which may or may not be possible depending on your circumstances.

- Talk with a financial advisor to see if they have any suggestions that might ease your tax burden next spring.

Louise Norris is an individual health insurance broker who has been writing about health insurance and health reform since 2006. She has written dozens of opinions and educational pieces about the Affordable Care Act for healthinsurance.org.