Home > States > Health insurance in Hawaii

See your Hawaii health insurance coverage options now.

Find affordable individual and family, small-group, short-term, or dental plans through licensed agency partners.

Hawaii Health Insurance Consumer Guide

Hawaii utilizes a federally run health insurance Marketplace, which means residents enroll through HealthCare.gov, where two private insurers offer individual/family health plans for Hawaii residents. But Hawaii still oversees the plans sold in the exchange.

(In 2014 and 2015, Hawaii ran its own exchange, but transitioned to HealthCare.gov in the fall of 2015 and has continued to use the federally-run platform ever since.)

For many people, an Affordable Care Act (ACA) Marketplace plan – called Obamacare or an exchange plan – may be a cost-effective choice. But finding the right plan can be tricky. This guide and the FAQs below are designed to help you understand your options so you can focus on your health!

Explore our other comprehensive guides to coverage in Hawaii

Dental coverage in Hawaii

In 2023, three insurers offer stand-alone individual/family dental coverage through the health insurance Marketplace in Hawaii.1 Learn about other dental coverage options in the state.

Hawaii’s Medicaid program

As of April 2023, 461,367 people were enrolled in Hawaii’s Medicaid program.2

Medicare in Hawaii

There are nearly 300,000 Medicare beneficiaries in Hawaii as of 2023.3 Read our overview of Medicare enrollment, including Hawaii’s rules on Medigap plans.

Short-term coverage in Hawaii

As of 2023, short-term health insurance plans are no longer being sold in Hawaii.4 Find out why in our guide to short-term coverage in Hawaii.

Frequently asked questions about health insurance in Hawaii

Who can buy Marketplace health insurance?

Virtually all residents of Hawaii are eligible to buy Marketplace health insurance with the following exceptions:5

- People who are not legally in the U.S.

- People already enrolled in Medicare

- People who are incarcerated

But eligibility for financial assistance in the Marketplace is a bit more involved. Eligibility for premium subsidies depends on how the cost of coverage in your area compares with your household income.

And to be eligible for subsidies you must not be eligible for Med-QUEST (Medicaid/CHIP), premium-free Medicare Part A,6 or an employer’s plan that’s considered affordable and comprehensive. However, most Marketplace enrollees do qualify for premium subsidies.

When can I enroll in an ACA-compliant plan in Hawaii?

Hawaii’s open enrollment period for individual and family health coverage is from November 1 to January 15. This is set by the federal government since Hawaii uses the federal exchange.

Here are some key dates to remember:7

- November 1: Open enrollment starts! This is when you can first sign up for or change plans for the following year. If you enroll by December 15, your coverage will begin on January 1.

- December 15: Last day to change plans or enroll for coverage to begin on January 1. After this date, any changes or new plans will start on February 1.

- January 15: Open enrollment ends.

After open enrollment, you can sign up for or make changes to an ACA Marketplace health through a special enrollment period (SEP). To be eligible for a SEP, you’ll need a qualifying life event.

Some SEPs don’t depend on a qualifying life event. For example:

- If you’re a Native American, you can enroll whenever necessary.8

- If you’re eligible for premium tax credits and your income is not more than 150% of the poverty level, you can enroll anytime until at least 2025.9

- People eligible for Medicaid/CHIP (Med-QUEST in Hawaii) can enroll in that coverage anytime.

How do I enroll in a Marketplace plan in Hawaii?

If you qualify for an ACA Marketplace plan, there are a variety of ways you can sign up, either during open enrollment or during a special enrollment period:

- Enroll online via HealthCare.gov.

- Enroll by phone at (800) 318-2596.

- Enroll in person, over the phone, or online with the help of an agent/broker, Navigator, certified application counselor, or an approved enhanced direct enrollment entity.10

How can I find affordable health insurance in Hawaii?

Hawaii’s uninsured rate has long been lower than the national average, due in large part to the state’s Prepaid Health Care Law, which has been in effect for nearly half a century.

Under this law, Hawaii’s employers must provide coverage to employees who work at least 20 hours per week, and the employee’s portion of the premiums can’t be more than 1.5% of their gross wages.11 So employer-sponsored health coverage is more accessible in Hawaii than it is in most of the rest of the country.

(A note about small group health insurance: Hawaii was the first state to receive approval for a 1332 waiver, which allowed Hawaii to no longer have a SHOP exchange.12 Small businesses in Hawaii purchase small group health plans directly from the insurers that sell these plans.)

But for those who aren’t eligible for an employer’s health plan or Medicare, coverage is available through the Marketplace (HealthCare.gov) or Med-QUEST (Medicaid/CHIP).

ACA Marketplace plans (on HealthCare.gov)

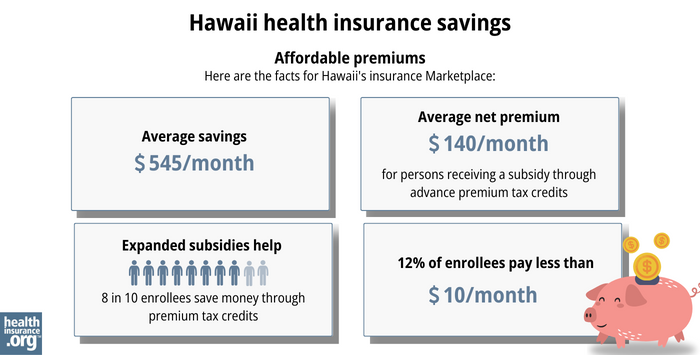

- About 83% of Hawaii Marketplace enrollees were receiving premium subsidies as of 2023.

- Subsidies – or Advance Premium Tax Credits (APTC) – help reduce premiums.

- The average premium subsidy for eligible enrollees is $545/month, meaning those subsidized enrollees pay an average of $140/month in premiums.13

- If your income is no more than 250% of the federal poverty level, you may qualify for cost-sharing reductions (CSR) to reduce your deductibles and out-of-pocket expenses, as long as you select a silver plan through the Marketplace.14 As of early 2023, 27% of Hawaii Marketplace enrollees were receiving premium subsidies.15

Medicaid

Hawaiians may find affordable coverage through Medicaid (Med-QUEST) if eligible.

How many insurers offer Marketplace coverage in Hawaii?

Two private insurance companies offer individual/family health coverage through Hawaii’s health insurance Marketplace.16

Are Marketplace health insurance premiums increasing in Hawaii?

According to Hawaii SERFF filings, the following average pre-subsidy rate changes were approved for 2024 (note that HMSA’s is slightly smaller than their originally proposed increase, which was 12.2%):17

Hawaii’s ACA Marketplace Plan 2024 Approved Rate Increases by Insurance Company |

|

|---|---|

| Issuer | Percent Increase |

| Hawaii Medical Service Association (HMSA) | 11.6% |

| Kaiser Foundation Health Plan, Inc. | 3% |

Source: HealthCare.gov16 and Hawaii SERFF18

As is always the case, these average premium changes are based on full-price premiums, but most enrollees are eligible for subsidies and thus do not pay full price. The subsidies are designed to keep pace with the cost of the benchmark plan in each area, so they grow when average benchmark premiums grow.

For perspective, here’s a summary of how average pre-subsidy premiums for ACA-compliant individual/family plans have changed each year in Hawaii:

- 2015: 7.8% increase19

- 2016: 30% increase20

- 2017: 30.7% increase21

- 2018: 32.8% increase22

- 2019: 5.3% increase23

- 2020: 4% decrease24

- 2021: 2.4% decrease25

- 2022: 1.6% increase26

- 2023: 2% increase27

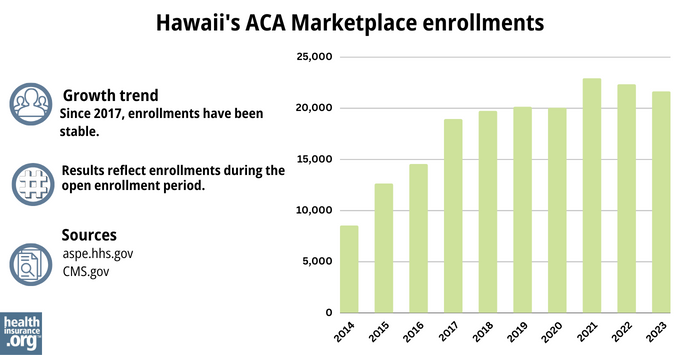

How many people are insured through Hawaii’s Marketplace?

During the open enrollment period for 2024 coverage, 22,170 people enrolled in private health insurance plans through the Hawaii Marketplace.28

Although nationwide Marketplace enrollment set a significant new record high in 2024, Hawaii’s enrollment was still a little lower than it had been in 202129 and 2022.30 But it was higher than 2023, when 21,645 people enrolled.13

Here’s a summary of how enrollment has changed over time in Hawaii’s Marketplace:

Source: 2014,31 2015,32 2016,33 2017,34 2018,35 2019,36 2020,37 2021,29 2022,30 202338

What health insurance resources are available to Hawaii residents?

HealthCare.gov

This is the ACA Marketplace, where you can enroll in a health insurance plan online. You may also get help by calling (800) 318-2596.

Hawaii’s Insurance Division of the Department of Commerce and Consumer Affairs

Licenses and regulates health insurers, agents, and brokers. They also handle consumer questions and complaints about insurance.

Legal Aid Society of Hawaii

The Navigator organization funded by the federal government in Hawaii.

Hawaii Medicaid (Med-QUEST)

This program provides health coverage for eligible residents.

Hawaii Prepaid Health Care Law information

This law helps ensure that many workers in Hawaii have access to health coverage through their jobs.

Louise Norris is an individual health insurance broker who has been writing about health insurance and health reform since 2006. She has written dozens of opinions and educational pieces about the Affordable Care Act for healthinsurance.org.

Footnotes

- “Hawaii dental insurance guide 2023” healthinsurance.org, Accessed September 2023 ⤶

- “April 2023 Medicaid & CHIP Enrollment Data Highlights” Medicaid.gov, April 2023 ⤶

- “Medicare Monthly Enrollment” CMS.gov, April 2023 ⤶

- “Availability of short-term health insurance in Hawaii” healthinsurance.org, March 7, 2023 ⤶

- ”A quick guide to the Health Insurance Marketplace” HealthCare.gov ⤶

- Medicare and the Marketplace, Master FAQ. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Accessed November 2023. ⤶

- “When can you get health insurance?” HealthCare.gov, 2023 ⤶

- “Who doesn’t need a special enrollment period?“ healthinsurance.org, Accessed August 2023 ⤶

- “An SEP if your income doesn’t exceed 150% of the federal poverty level” healthinsurance.org, Feb. 1, 2023 ⤶

- “Entities Approved to Use Enhanced Direct Enrollment” CMS.gov, April 28, 2023 ⤶

- ”Highlights of the Hawaii Prepaid Health Care Law” State of Hawaii, Department of Labor and Industrial Relations. ⤶

- ”Hawaii Section 1332 Waiver Extension” Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. December 10, 2021. ⤶

- “2023 Marketplace Open Enrollment Period Public Use Files” CMS.gov, March 2023 ⤶ ⤶

- “Federal Poverty Level (FPL)” HealthCare.gov, 2023 ⤶

- ”Effectuated Enrollment: Early 2023 Snapshot and Full Year 2022 Average” Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. ⤶

- ”Hawaii Rate Review Submissions” HealthCare.gov, 2023 ⤶ ⤶

- ”Hawaii SERFF Filings” August 2023 ⤶

- ”Hawaii SERFF Filings” August 2023 ⤶

- ”Hawaii: Final 2015 QHP Rate Increase: 7.8%; SHOP Plans *Drop* 3.5%” ACA Signups. November 13, 2024 ⤶

- ”FINAL PROJECTION: 2016 Weighted Avg. Rate Increases: 12-13% Nationally” ACA Signups. October 15, 2015. ⤶

- ”Avg. UNSUBSIDIZED Indy Mkt Rate Hikes: 25% (49 States + DC)” ACA Signups. August 14, 2016. ⤶

- ”2018 Rate Hikes” ACA Signups. ⤶

- ”Release: HAWAII 2019 Affordable Care Act Individual Rates” Hawaii Department of Commerce and Consumer Affairs. October 2018 ⤶

- ”2020 Rate Changes” ACA Signups ⤶

- ”Hawaii SERFF Filings” Accessed September 2023 ⤶

- ”2022 Rate Changes” ACA Signups. ⤶

- ”UPDATED: FINAL Unsubsidized 2023 Premiums: +6.2% Across All 50 States +DC” ACA Signups. ⤶

- Marketplace 2024 Open Enrollment Period Report: Final National Snapshot. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. January 2024. ⤶

- “2021 Marketplace Open Enrollment Period Public Use Files” CMS.gov, 2021 ⤶ ⤶

- “2022 Marketplace Open Enrollment Period Public Use Files” CMS.gov, 2022 ⤶ ⤶

- “ASPE Issue Brief (2014)” ASPE, 2015 ⤶

- “Health Insurance Marketplaces 2015 Open Enrollment Period: March Enrollment Report”, HHS.gov, 2015 ⤶

- “HEALTH INSURANCE MARKETPLACES 2016 OPEN ENROLLMENT PERIOD: FINAL ENROLLMENT REPORT” HHS.gov, 2016 ⤶

- “2017 Marketplace Open Enrollment Period Public Use Files” CMS.gov, 2017 ⤶

- “2018 Marketplace Open Enrollment Period Public Use Files” CMS.gov, 2018 ⤶

- “2019 Marketplace Open Enrollment Period Public Use Files” CMS.gov, 2019 ⤶

- “2020 Marketplace Open Enrollment Period Public Use Files” CMS.gov, 2020 ⤶

- “Health Insurance Marketplaces 2023 Open Enrollment Report” CMS.gov, 2023 ⤶