Medicaid Eligibility and Enrollment Guide

An overview of federal and state Medicaid eligibility, benefits and enrollment.

What is Medicaid?

Medicaid is a government-run health coverage program for low-income people in the United States.1 As of early 2025, the program provided comprehensive coverage with low out-of-pocket costs to more than 71 million people.2

Medicaid is jointly funded by the federal and state governments, and administered by each state1 so eligibility guidelines and benefits vary significantly from state to state.

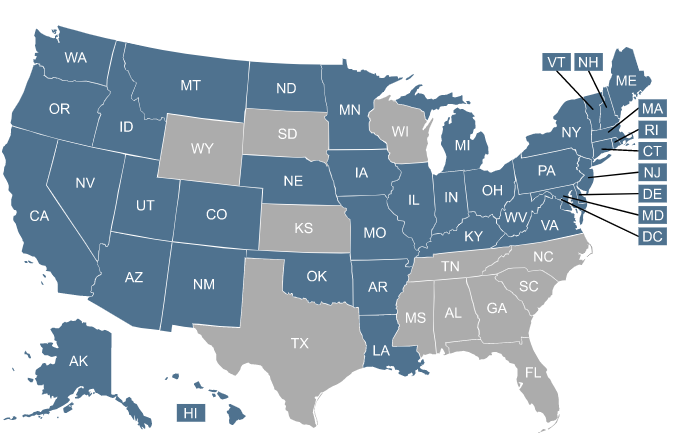

Click on the map or the list of states to learn more about Medicaid in your state.

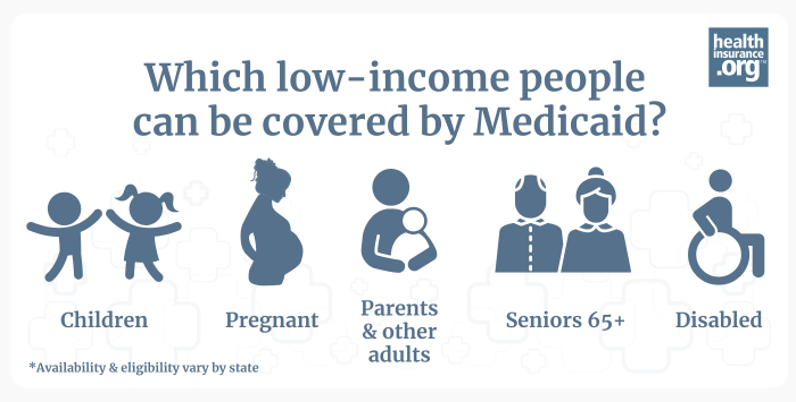

Who is eligible for Medicaid?

Medicaid eligibility rules vary from one state to another, so a person who is eligible for Medicaid in one state might not be eligible in another. Medicaid eligibility is based primarily on income – and for some populations, both income and assets – with specific guidelines set by each state.

Find out: Can I use my Medicaid coverage in any state?

Financial eligibility for Medicaid based only on income (as opposed to both income and assets) applies to:3

- Children

- Pregnant women

- Parents of minor children

- Adults under age 65 who are eligible due to Medicaid expansion

The specific income levels that make those populations eligible for Medicaid are different in each state4 (and not all states have expanded Medicaid eligibility). Income limits are shown as a percentage of the federal poverty level (FPL) which is updated annually.5

Learn more: Medicaid for children: Six facts every parent should know.

In addition to the populations listed above, additional populations can qualify for Medicaid if they have both a low income and low asset/resource levels. They include:6

- People age 65 and older

- People whose eligibility is based on disability or blindness

For these populations, the allowable income7 and asset levels8 also vary by state.

Are you losing Medicaid eligibility? Here’s what to do next.

Who gained coverage under Medicaid expansion?

Medicaid expansion refers to state action permitted by the Affordable Care Act (ACA) to expand coverage to more low-income adults. Before 2014, low-income adults could generally qualify for Medicaid only if they fit into one of the other eligibility categories (pregnant, disabled, or the parent/caretaker of a minor child). But the ACA created a new eligibility pathway for adults under age 65 whose household income isn’t more than 138% of the federal poverty level.9

This was intended to be available nationwide, but a 2012 U.S. Supreme Court ruling allowed states to continue to receive their existing federal Medicaid funding even if they didn’t expand Medicaid.1011

This essentially made Medicaid expansion optional for states, and there are still 10 states that have not expanded Medicaid as of 2025.12 In nine of those states, adults with income under the federal poverty level fall into a “coverage gap” if they aren’t eligible for Medicaid due to pregnancy, being a parent/caretaker of a minor child, or disability. This means that some adults in those nine states are both ineligible for Marketplace subsidies (making coverage too expensive) because their incomes are below the poverty level, and also ineligible for Medicaid because their states have not expanded Medicaid to cover low-income adults.

Find out whether your state has implemented Medicaid expansion.

How do I apply for Medicaid?

You can apply for Medicaid online, by mail, over the phone, or in person, depending on where you live.13

You can also begin the process by visiting the health insurance Marketplace in your state (HealthCare.gov or a state-run Marketplace). In some states, you can complete Medicaid enrollment via the Marketplace website.14 But in most states, the Marketplace will transfer your information to the state Medicaid agency if it looks like you’re eligible, and Medicaid will contact you to complete the application process.15

Since Medicaid is administered separately by each state, the enrollment process and eligibility rules vary by state. But unlike other types of health coverage, Medicaid enrollment is open year-round.16 So you can apply anytime, without needing a qualifying life event.

What documents do I need to apply for Medicaid?

The specifics will vary depending on where you live, but you will likely need to provide the following information to apply for Medicaid:15

- Name, date of birth, and Social Security number for all household members applying for Medicaid.

- Proof of residence in the state where you’re applying for Medicaid.

- Proof of income, such as pay stubs or a W-2. (Depending on the circumstances, you might also need to provide proof of expenses, including medical expenses.)17

- Proof of citizenship or immigration status. (You generally need to be lawfully present in the U.S. for at least five years to be eligible for Medicaid, although that’s not always the case, especially for children and pregnant women.)18

- Details about any other government benefits you receive, such as Social Security or SNAP.

- Information about any other insurance you might have, or a coverage offer from an employer. (Some states use Medicaid funds to help eligible applicants pay for employer-sponsored health insurance.)19

Search for health coverage by working with a licensed agency.

What does Medicaid cover?

There are some services that Medicaid is required to cover in every state, and other services that are optional for states to cover.20 As a result, Medicaid benefits differ from one state to another.

Learn more about what Medicaid covers.

Medicaid coverage typically means low or zero out-of-pocket costs for the enrollee. The specifics vary depending on the state and the care that’s provided, but total enrollee costs can’t be more than 5% of a household’s income.21

Starting in October 2028, under the terms of the “One Big Beautiful Bill” that was enacted in July 2025, some services for Medicaid expansion enrollees will have new copays of up to $35. But the total cap of 5% of household income will still be applicable.22

What is the difference between Medicare and Medicaid?

Medicare and Medicaid are both government-run health coverage programs. But they have several key differences, including:1

| Medicare vs. Medicaid | ||

|---|---|---|

| Medicaid | Medicare | |

| Funding | Medicaid is jointly funded by the federal and state governments and administered by the states. | Medicare is funded and administered by the federal government. |

| Eligible for coverage | Medicaid enrollment is available to low-income people. (Income limits vary by population, so they’re different for children, pregnant woman, etc.) Some people are eligible for both Medicare and Medicaid. | Medicare is available to people 65 and older or people with long-term disabilities, ERSD, or ALS. Some people are eligible for both Medicare and Medicaid. |

| Coverage of custodial care | Yes | No |

| Premiums | Medicaid does not have a premium in most states. 23 | Medicare has a premium for Medicare Part B (and Medicare Part A, if the person doesn’t have enough work history to qualify for premium-free Part A).24 |

How is Medicaid funded?

Medicaid is jointly funded by the federal government and each state’s government. The funding split for traditional Medicaid (meaning everyone except the Medicaid expansion population) depends on the average per-capita income in the state, with higher federal funding going to states with lower average per-capita incomes.25

For the Medicaid expansion population, the federal government pays 90% of the cost and states pay 10% of the cost. This 90/10 split does not vary by state.

When we include both the traditional Medicaid population and the Medicaid expansion population, the federal government pays roughly 50% to 80% of total Medicaid costs, depending on the state.

Frequently asked questions about Medicaid

Does Medicaid cover undocumented immigrants?

In most states, undocumented immigrants are not eligible for Medicaid coverage. But some states use only state funding, with no federal matching funds, to provide Medicaid or similar coverage to undocumented immigrants. (Federal funding cannot be used to provide Medicaid to undocumented immigrants, and is generally only available to pay for emergency medical care if the patient is an undocumented immigrant.)26

Does Medicaid cover dental, vision, and hearing?

Medicaid rules provide that dental, vision, and hearing care for enrollees under age 21 are each a mandatory benefit, which means Medicaid programs in all states must provide the coverage.27

For Medicaid enrollees who are 21 or older, dental benefits are optional for states to provide, so coverage varies from one state to another. The same is true for vision28 and hearing benefits.29

Does Medicaid cover mental health services?

Yes, Medicaid covers mental health care, and is the largest payer for mental health services in the United States.30

But as with other types of care, there’s state-to-state variation in terms of the specific mental health benefits that Medicaid provides.

Does Medicaid cover long-term care or nursing homes?

Yes, Medicaid covers custodial long-term care. Medicaid is the primary payer of nursing home costs for more than six out of ten U.S. nursing home residents.31

In almost all states, Medicaid also covers in-home custodial long-term care.32 This allows enrollees to remain in their homes while receiving Medicaid-funded assistance with activities of daily living such as bathing and dressing.

To be eligible for Medicaid coverage of custodial long-term care, an applicant’s income and assets must be within the state’s required levels.32

States also check to make sure that the person didn’t transfer assets to someone else for less than fair market value within a certain time frame (five years in most states) before applying for Medicaid coverage of long-term care. If they did, they would have a waiting period before they could become eligible for long-term care coverage under Medicaid.33

Does Medicaid cover prescription drugs?

Can I get Medicaid if I’m unemployed?

For the time being, employment status does not impact eligibility for Medicaid. That will change in 2027, under the terms of the “One Big Beautiful Bill” that was enacted in 2025. That legislation will require Medicaid expansion enrollees to document at least 80 hours per month of “community engagement” such as work, school, or volunteering.35

But for now, in most states, you can qualify for Medicaid if you’re unemployed and have no income. This depends in large part on whether your state has expanded Medicaid, as described below.

If the state has expanded Medicaid, it’s available to adults under age 65 with income up to 138% of the federal poverty level.9 And Medicaid eligibility can be determined based on current monthly income, regardless of whether a person had a higher income earlier in the year. (This differs from Marketplace premium subsidies, which are always based on total annual income.)36

In a state where Medicaid has been expanded in the continental U.S., a single person can qualify for Medicaid with a 2025 income between $0 and $21,597 (or up to about $1,800/month).37

In a state where Medicaid has not been expanded, an adult with no income will not be eligible for Medicaid unless they’re eligible due to pregnancy, being a parent/caretaker of a child, or disability.38 But a person in that situation might be eligible for a Marketplace subsidy based on the income they earned earlier in the year.

Learn more about health insurance options for the unemployed.

Footnotes

- “What’s the difference between Medicare and Medicaid?” U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Accessed June 10, 2025 ⤶ ⤶ ⤶

- “January 2025 Medicaid & CHIP Enrollment Data Highlights” Medicaid.gov. Accessed June 10, 2025 ⤶

- “Eligibility Policy” Medicaid.gov. Accessed June 9, 2025 ⤶

- “Medicaid, Children’s Health Insurance Program, & Basic Health Program Eligibility Levels” Medicaid.gov. Accessed June 19, 2025 ⤶

- ”Poverty Guidelines” U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Accessed June 26, 2025 ⤶

- “Medicaid Eligibility and Enrollment Policies for Seniors and People with Disabilities (Non-MAGI) During the Unwinding” KFF.org. June 20, 2024 ⤶

- “Medicaid Eligibility Income Chart by State (Updated Jun. 2025)” American Council on Aging. June 4, 2025 ⤶

- ”What your state lets you keep, effective 1/1/2025” GotLTCI. Jan. 1, 2025” ⤶

- “5 Key Facts About Medicaid Expansion” KFF.org. Apr. 25, 2025 ⤶ ⤶

- “A Guide to the Supreme Court’s Decision on the ACA’s Medicaid Expansion” KFF.org. Aug. 2012 ⤶

- Under the ACA, a state that didn’t expand Medicaid would have potentially lost all federal Medicaid funding, but the Supreme Court ruling prevented that. ⤶

- “Status of State Medicaid Expansion Decisions” KFF.org. May 9, 2025 ⤶

- ”Where Can People Get Help With Medicaid & CHIP?” Medicaid.gov. Accessed June 19, 2025 ⤶

- “Understanding Integration Between State-Based Marketplaces and Medicaid” State Marketplace Network. Mar. 4, 2024 ⤶

- “How to apply for Medicaid and CHIP” USA.gov. Accessed June 10, 2025 ⤶ ⤶

- “Medicaid & CHIP coverage” HealthCare.gov. Accessed June 10, 2025 ⤶

- “Eligibility Policy; Medically Needy” Medicaid.gov. Accessed June 10, 2025 ⤶

- “5 Key Facts About Immigrants and Medicaid” KFF.org. Feb. 19, 2025 ⤶

- “Federal Requirements and State Options: Premium Assistance” MACPAC. Accessed June 10, 2025 ⤶

- “Mandatory & Optional Medicaid Benefits” Medicaid.gov. Accessed June 10, 2025 ⤶ ⤶

- “Cost Sharing Out of Pocket Costs” Medicaid.gov. Accessed June 10, 2025 ⤶

- “H.R. 1, The One Big Beautiful Bill Act” (Section 71120). Enacted July 4, 2025 ⤶

- “Understanding the Impact of Medicaid Premiums & Cost-Sharing: Updated Evidence from the Literature and Section 1115 Waivers” KFF.org. Sep. 9, 2021 ⤶

- “Costs” Medicare.gov. Accessed June 10, 2025 ⤶

- “Medicaid Financing: The Basics” KFF.org. Jan. 29, 2025 ⤶

- ”CMS Increasing Oversight on States Illegally Using Federal Medicaid Funding for Health Care for Illegal Immigrants” Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. May 27, 2025 ⤶

- “Mandatory & Optional Medicaid Benefits” And “Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic, and Treatment” Medicaid.gov. Accessed June 10, 2025 ⤶

- “Medicaid vision coverage for adults varies widely by state” National Institutes of Health. Aug. 6, 2024 ⤶

- “Hearing Aids and Medicaid” Most Policy Initiative. Feb. 3, 2025 ⤶

- “Behavioral Health Services” Medicaid.gov. Accessed Apr. 30, 2025 ⤶

- “A Look at Nursing Facility Characteristics Between 2015 and 2024” KFF.org. Dec. 6, 2024 ⤶

- “Answers to All of Your Questions About Medicaid Long Term Care” American Council on Aging. Mar. 25, 2025 ⤶ ⤶

- “Understand Medicaid’s Look-Back Period; Penalties, Exceptions & State Variances” American Council on Aging. Nov. 21, 2024 ⤶

- “Prescription Drugs” Medicaid.gov. Accessed June 10, 2025 ⤶

- “H.R. 1, The One Big Beautiful Bill Act” (Section 71119). Enacted July 4, 2025 ⤶

- “Health Insurance Marketplace Calculator, FAQs: What is Medicaid? How does it relate to financial help through the Health Insurance Marketplace?” KFF.org. Accessed June 10, 2025 ⤶

- “2025 Poverty Guidelines: 48 Contiguous States (all states except Alaska and Hawaii)” U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Accessed June 10, 2025 ⤶

- “Medicaid expansion & what it means for you” HealthCare.gov. Accessed June 10, 2025 ⤶